Back in the summer of 2024, Minnesota utility Xcel Energy proposed a novel approach to building virtual power plants, the networks of rooftop solar systems, home batteries, and other energy equipment that can operate in tandem to reduce strain on the electric grid.

Instead of working with other companies to cobble together solar arrays and batteries at homes and businesses — the traditional model for VPPs — Xcel wanted to install, own, and control those devices itself, using its grid expertise to deliver a better bargain for its customers at large.

Now, a year and a half later, the plan is in — and clean energy advocates, solar industry groups, and state agencies say it doesn’t live up to Xcel’s promises.

In filings with the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, these groups say Xcel’s Capacity*Connect (C*C) plan, unveiled in October, is likely to be slower, more costly, and less impactful in relieving grid stresses and energy costs than the customer-centered VPP programs already in place or being rolled out — including one by Xcel in Colorado.

As Minnesota’s Office of the Attorney General wrote in its initial comments, “Although Xcel suggests that C*C is uniquely innovative, it may simply be a uniquely expensive way to accomplish the same thing other states have accomplished for less ratepayer money.”

Xcel is asking for permission to spend at least $152 million to deploy 50 megawatts of batteries, and up to $430 million for 200 megawatts, through 2028. Those costs will be borne by its customers. And as capital expenditures, they will offer the utility a guaranteed profit on every dollar spent — a perk Xcel wouldn’t get if it relied on the traditional VPP model.

In its petition to regulators, Xcel says the plan is a first step in learning how to best integrate distributed energy resources across its grid, as called for by state utility policy for the past decade. It also argued that “non-utility-owned resources could deliver, at best, a portion of the anticipated system and customer benefits.”

Backers of this utility-led approach include Jigar Shah, a Biden administration Department of Energy official who has long championed the value of using batteries and other distributed energy resources — DERs in the jargon — as an alternative to big, costly, and hard-to-build power plants and transmission lines.

“For the first time in my professional career, we have a utility company formally agreeing with the fact that distributed power plants are essential to maintaining reliability and meeting load growth,” Shah wrote in a December LinkedIn post. “This is a huge win for our entire industry, and efforts by industry groups to torpedo this proposal can’t see the forest for the trees.”

But John Farrell, co-director of the nonprofit consumer advocacy group Institute for Local Self-Reliance and a longtime utility critic, argues that Xcel Energy is trying to monopolize the grid value of solar and battery systems, which customers are already willing to pay for to save money and provide backup power.

Utility ownership might be an acceptable alternative if it could be done faster and cheaper than the VPPs being put together by solar and battery installers like Sunrun, Tesla, and a host of other companies, Farrell said. But “if utilities are supposed to be so good at this, why is the cost-benefit analysis underwater?” he asked. “And why is it so slow?”

Logan O’Grady, executive director of the Minnesota Solar Energy Industries Association, doesn’t want to be too critical of Xcel’s plan. After all, his group and other solar advocates have spent years pushing utilities to rely more on rooftop solar, backup batteries, and other DERs. It hasn’t been easy. Utilities have long been leery of the reliability of these technologies, and instead prefer tried-and-true grid upgrades and utility-controlled equipment.

“This has been a tricky one, because for 10 years, people on our side have been saying to the commission and utilities, there’s value in the distribution system — you should invest there,” he said.

That argument is backed by an analysis from the DOE, promoted by Shah during his tenure, that found rooftop solar systems, backup batteries, electric vehicles, smart thermostats, and grid-responsive water heaters could provide 80 to 160 gigawatts of VPP capacity by 2030 in the U.S. That would be enough to meet 10% to 20% of the nation’s peak grid needs and save utility customers roughly $10 billion in annual grid costs.

“So when [Xcel’s] proposal first came out, in one sense it was like, ‘They’re finally listening to us,’” O’Grady said. “But in another sense it was, ‘They’re going too far by proposing only utility ownership.’”

That’s a significant departure from the status quo, the Minnesota Solar Energy Industries Association, Coalition for Community Solar Access, and Solar Energy Industries Association trade groups wrote in comments to the Minnesota PUC. “Traditional VPPs are technology-agnostic portfolios of customer-sited and third-party-owned resources,” they wrote. “Participation is open, competitive, and decentralized.”

By contrast, Xcel’s C*C plan would rely completely on utility-owned batteries of between 1 and 3 megawatts, the kind that usually come in shipping containers. Xcel plans to pay an undisclosed amount to businesses or nonprofits willing to host those batteries on their properties. But rather than connecting the equipment in those customers’ buildings, the utility would instead connect the batteries directly to its grid, preventing them from providing emergency backup power to participating customers.

To secure customers willing to host those batteries, Xcel Energy has proposed hiring Sparkfund, a company founded in 2013 that has promoted the “distributed capacity procurement” concept that forms the basis of the C*C plan. Xcel’s plan marks its first stab at implementing distributed capacity procurement.

But deploying utility-owned batteries via a single commercial partner is “unprecedented in VPP programs and raises significant competitive-market concerns,” the solar trade groups wrote.

Chris Villarreal, president of consultancy Plugged In Strategies and former director of policy at the Minnesota PUC, shares those concerns. In comments filed on behalf of the R Street Institute, a free market–oriented think tank where he serves as an associate fellow, Villarreal recommended that regulators reject the plan or, at a minimum, “ensure Xcel does not exercise monopoly power at the expense of other competitive and potentially lower-cost alternatives.”

“There are a couple of things that annoy me about this from a practical perspective,” Villarreal told Canary Media. “One is the exercise of monopoly power over competitors.” Xcel is proposing to give Sparkfund access to grid and customer data that “no competitor would be able to get” without signing nondisclosure agreements, he said. “Meanwhile, we have community solar gardens, solar developers, storage developers, that want to do the same thing.”

This lack of grid transparency is troubling, O’Grady said, given Xcel’s track record of making it difficult for customers and third-party developers to add batteries and community and rooftop solar to its grid. “Minnesota has a grid-congestion problem, and lack of utility investment to solve that problem,” he said.

At the very least, Xcel should subject its battery systems to the same process third-party developers and customers must go through to connect to the grid, O’Grady said. Under the C*C plan, “they circumvent that entire waitlist to interconnect — and that doesn’t seem fair.”

State regulators anticipated these concerns. The Minnesota PUC’s 2024 order allowing Xcel Energy to pursue the C*C plan required the utility to compare the costs and benefits with those of “alternative models” using customer and third-party-owned resources.

But Xcel Energy appears to have short-shrifted that requirement, said Erica McConnell, a staff attorney at the nonprofit Environmental Law & Policy Center. Instead of offering a cost comparison, Xcel asserted in its petition that “anything less than full operational control and visibility of these assets — which will operate functionally as part of our system — could present safety risks for our employees and the public and could create cybersecurity risks for our system.”

These statements appear to ignore the experience of other utilities managing VPP programs, McConnell said. In essence, she said, the utility dismissed the prospect of alternative approaches by saying, “‘It’s dangerous if we let other parties do it.’ That’s disappointing to us. We need alternative pathways.”

Xcel Energy disputes that it ignored regulators’ instructions. The utility lacks “quantitative information” on those alternatives, and “would need to speculate on these costs and benefits, which would inevitably lead to unresolvable disputes,” it wrote in reply comments.

Xcel also highlighted that it’s offering customers and third-party developers other pathways to add solar and batteries to its grid, including its long-running community solar program and incentives for backup batteries. Nearly all of the more than 1.3 gigawatts of distributed solar and storage on Xcel’s system in Minnesota is owned by third parties, it noted.

But the C*C program is focused on solving a much broader range of challenges on its grid, which requires greater precision than Xcel can achieve from customer-owned batteries, the utility said. It argues that it needs such rigorous control over the systems to cut costs and improve overall grid reliability for customers at large, in what it called a “marked shift in distributed energy policy.”

Critics have their doubts, however, about whether the benefits of Xcel’s plan will outweigh the costs.

The Minnesota Office of Attorney General wrote in its comments that it supports efforts to meet the state’s carbon-cutting goals while keeping rising energy and grid costs in check. But it also asked regulators to put a “hard cap” on Xcel’s spending, noting that it “stands to be a quite expensive program.”

Xcel’s C*C budget calls for spending up to $430 million for deploying 200 megawatts of batteries, it wrote, which equates to $2,150 per kilowatt of battery installed — well above typical costs for grid batteries.

It’s also more expensive than what Xcel Energy intends to spend on a gas-fired “peaker” power plant it’s planning to build in Lyon County, Minnesota, the office noted. That’s despite data from DOE’s VPP report indicating that typical VPP capacity can be more than 40% cheaper than that of conventional peaker plants, which run only at times of extremely high demand.

And Xcel’s proposed budget is well above what the Public Service Co. of Colorado, Xcel Energy’s utility in that state, intends to spend on its proposed Aggregator Virtual Power Plant pilot program. That program will pay third-party aggregators that equip customers with resources — including batteries, smart thermostats, smart water heaters, smart heat pumps, and EV chargers — that can inject electricity onto the grid or reduce power use. It is targeting 125 megawatts of capacity for a five-year budget of $78.5 million, or roughly $625 per kilowatt.

Xcel says these comparisons don’t tell the whole story. The Colorado program covers only five years of payments to aggregators, while the Minnesota program is modeled to cover the cost of assets for 20 years, Xcel spokesperson Theo Keith told Canary Media in an email. “When you model both programs over 20 years, their costs are similar.”

“Capacity*Connect will be more complex to operate and coordinate than the Colorado [program],” Keith added, because it’s designed to do more than simply reduce peak electricity demands across the entire grid.

Instead, C*C is meant to target particular points on the utility’s distribution grid that might otherwise need costly upgrades. This is the portion of the system that, unlike giant transmission lines that cover long distances, brings power directly to homes and businesses. Costs related to the distribution grid are the single biggest driver of rising utility bills in the U.S.

“Through the deployment of distributed batteries, we (and thus our customers) will save more money by avoiding more expensive grid upgrades than the payments made to program participants,” Keith wrote.

But Xcel’s plan will take years to use its batteries for this kind of deferral. Its initial phase will limit them to reducing systemwide energy and capacity costs — the same kind of task that demand-response programs have been doing for decades. Not until “Phase 3” of its plan, set for between 2028 and 2031, will Xcel “seek opportunities to stack additional distribution value streams,” like finding ways for batteries to defer costly grid upgrades.

Delaying that work doesn’t sit well with nonprofit groups such as the Environmental Law and Policy Center, Vote Solar, Solar United Neighbors, and Farrell’s Institute for Local Self-Reliance. In their comments, they asked the Minnesota PUC to require Xcel to set a mid-2027 deadline to “take concrete steps to advance distribution value” — and to set up a way for third-party and customer-owned technologies to participate.

The Minnesota Department of Commerce concurred. In its comments to regulators, it laid out a series of changes that it and clean energy advocacy groups agreed Xcel should make to its plan to more quickly take on the advanced grid services it’s currently proposing to delay for years to come.

For one, the department recommended that regulators require Xcel to target its batteries to fix known reliability issues or “defer specific, budgeted infrastructure investments” on the distribution grid — something that utilities in California, Massachusetts, and other states are doing in pilot projects.

Another recommendation for Xcel that’s being done by other utilities is to use its batteries to make room on congested parts of the grid for more customer-owned or community solar to come online. That could help solve the long-standing interconnection bottlenecks that rooftop and community solar providers have been complaining about.

Shannon Anderson, a policy director at the nonprofit Solar United Neighbors, which helps households organize to secure cheaper rooftop solar, highlighted one big difference between the approaches taken by Xcel in Minnesota and in Colorado. In Colorado, the utility’s VPP approach is guided by a law passed by the state legislature in 2024. Minnesota lacks such a policy; a VPP bill failed to pass last year, although its sponsors plan to reintroduce the legislation this year.

“The Minnesota story is part of a national trend,” said Anderson, who is leading Solar United Neighbors’ work with a coalition sponsoring VPP legislation in multiple states. “The more legislative direction can give them guidance and political support, the better.”

A massive new battery has entered service in southern Maine, providing a much-needed boost to the Northeast’s efforts to expand clean and affordable energy.

Developer Plus Power wrapped up its Cross Town Energy Storage project in late November, but publicly inaugurated it last week in a ceremony featuring Gov. Janet Mills, a Democrat, who has championed clean energy for the state and is currently running for Senate. Now, the small town of Gorham, nine miles inland from Portland, hosts a battery plant capable of injecting 175 megawatts for up to two hours, a bigger capacity than any other battery in New England.

“During Winter Storm Fern, we were 100% available and ready to contribute capacity with no emissions,” said Polly Shaw, chief external relations officer at Plus Power. “With a response capability of 250 milliseconds, there’s no faster asset that New England can rely on to help when they need capacity or grid services.”

New England states have issued a raft of energy storage targets in recent years, meant to complement their bevy of commitments to grid decarbonization. By 2030, Massachusetts aims to have 5 gigawatts, Connecticut 1 gigawatt, and Maine 400 megawatts. So far, however, it’s been slow going, even as storage has taken off in states like California and Texas. New England has managed to build just two battery installations with more than 100 megawatts: Plus Power’s Cross Town and its 150-megawatt Cranberry Point Energy Storage project, which came online in Massachusetts in June.

Plus Power has distinguished itself by entering into markets before they become saturated. For these two projects, the company won seven-year contracts in a 2021 forward capacity auction for the Independent System Operator New England, which runs wholesale power markets for the region’s six states. ISO-NE subsequently switched its capacity auctions to one-year awards — a move that complicates storage development in the region, as short-term contracts make it harder to attract project financing.

As it stands, Plus Power can claim the federal investment tax credit for 30% of the cost of the storage plant. Then it can earn revenue from the capacity contract and by bidding ancillary services in the wholesale market. Batteries can also arbitrage energy by buying when it’s cheap (typically when there’s an influx of renewable production) and selling when it’s expensive (typically when there’s increased reliance on gas-burning peaker plants).

Plus Power hired 25 full-time employees during construction of Cross Town and will employ two permanent maintenance staff now that the largely automated facility is running. It will contribute $8 million in tax revenue to Gorham, Shaw said.

Cross Town has an advantageous location in southern Maine, near Portland, the state’s biggest city. That allows it to work around transmission constraints, charging up when onshore wind farms are producing farther north, and then making that power available when Portland or points south need it, Shaw noted.

This serves Maine’s target of having 90% renewable and 100% clean energy by 2040, among the more assertive clean-energy goals in the country. Batteries can help this goal by improving utilization of renewable electricity. Maine also passed its 2030 storage mandate in 2021; Gorham knocked out nearly half of that single-handedly.

The state is planning a competitive storage solicitation this year to keep moving toward the target.

“Maine is such a leader on renewable energy, climate policy, and battery storage policy that it sent a long-term signal to come and invest in Maine,” Shaw said.

The battery could also tie into evolving conversations around energy affordability, which has become a primary political concern around the country. Mainers pay among the highest rates in the country for electricity and home heating. State energy analysts recently published a report that pinpointed fossil gas prices as a key driver of higher energy prices, since gas-burning plants typically set the market price for power in the region. Batteries provide peak power on demand without burning gas — and a broader build-out of facilities like Cross Town could put downward pressure on those sky-high prices.

Since the late 1800s, the grid has used more or less the same devices to convert electricity to different voltages. They’re called transformers — and they’re in increasingly short supply as power demand surges nationwide.

A crop of startups wants to solve that problem and modernize transformer technology at the same time — and they’re raising financing to do it.

On Wednesday, solid-state transformer startup Heron Power closed a $140 million Series B round from investors including Andreessen Horowitz’s American Dynamism Fund and Breakthrough Energy Ventures.

The new financing will allow the Northern California–based startup to build a factory at a yet-to-be-disclosed U.S. location capable of churning out 40 gigawatts of its medium-voltage power-conversion gear annually. It plans to start full-scale production in the second half of 2027 and have hundreds of megawatts of equipment produced by the end of that year.

Heron Power has already lined up 50 gigawatts of orders with more than a dozen prospective customers that are “actively engaged in technical product collaborations,” according to CEO Drew Baglino, who founded the startup in 2025 after an 18-year career at Tesla.

The firm is looking to initially sell not to utilities but rather to operators of solar and battery farms and data center campuses, which need to convert electricity as well. So far, it has disclosed only two of its early customers: Intersect Power, a major clean-energy developer that Google is acquiring for $4.75 billion, and Crusoe, a data center developer building a 1.2-gigawatt campus in Abilene, Texas.

While Baglino declined to share details about other prospective customers, he did say that Heron Power has been bringing many of them into its lab to see the prototype equipment being put through its paces. “We’re also doing integrated full-system deployments later this year,” he said. “It helps immensely for folks to get a sense of what we’re talking about and see the power processing in front of them.”

Heron Power isn’t the only company building next-generation power-conversion equipment. DG Matrix is planning to deploy its solid-state transformer via strategic partnerships with PowerSecure, a major developer of microgrids and data-center power systems that’s owned by utility Southern Co., and with Exowatt, a startup providing solar and thermal energy storage systems to data centers.

On Wednesday, the Raleigh, North Carolina–based DG Matrix announced a $60 million investment led by Engine Ventures and including Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and electrical-equipment manufacturing giant ABB. The Series A funding will enable the company to scale up manufacturing and deepen “strategic partnerships with datacenter developers, hyperscalers, utilities, and industrial customers,” according to the company’s press release.

Another startup in the space, Resilient Power, was acquired last year by electrical equipment giant Eaton in a deal worth as much as $150 million.

Solid-state transformers digitally manipulate the flow of electricity, employing the same kind of power electronics that are used in solar and battery inverters and in electric vehicle drivetrains. “Solid state” refers to the semiconductors that make that digital power manipulation possible. “Transformers” is a nod to the 19th-century electromechanical devices that convert the voltage of alternating current via copper wires wound around iron cores.

Solid-state transformers are a timely replacement for those devices for a couple of reasons. They’re far more flexible than old-school electromagnetic devices, meaning engineers can do more things with one device. They’re also urgently needed because conventional power equipment — particularly transformers — has been unable to keep up with the demand created by the fast-growing electricity sector.

The technology itself is not brand new. High-frequency digital power-switching technologies are already used for specialized purposes such as massive high-voltage direct current (HVDC) converters. And inverters — another form of digital power-switching tech — are an integral part of EV chargers and solar and battery installations.

Over the past decade or more, various efforts to expand the role of solid-state power-conversion technologies to replace a wider array of systems have struggled to gain traction, given high costs and technical challenges. But Heron Power’s Baglino thinks that the time is right for this tech, as costs come down and major customers seek out effective alternatives to the backlogged and increasingly expensive conventional options.

As with many other digital technologies, “power semiconductors have had their own version of Moore’s law,” Baglino said. In the past five years or so, these improvements have made it “not only feasible but economically attractive to replace inverter skids — with an old-school transformer at solar and battery facilities — with a power electronics solution.”

Those “inverter skids” he mentioned are shipping-container-size combinations of electrical gear — step-down and step-up transformers, switching and protection gear, and inverters themselves — that convert direct current from solar panels and batteries to grid-ready alternating current. Similar combinations of gear are used to convert grid electricity to direct current needed to power heftier commercial and industrial sites — such as data centers.

Unlike traditional high-efficiency transformers, solid-state power-conversion devices don’t need specialized grain-oriented electrical steel, which is now in short supply. Instead, they use the same silicon carbide and gallium arsenide semiconductor supply chains feeding EV markets, Baglino said, “and the EV supply chain has expanded rapidly over the past decade or so.”

Solid-state transformers also weigh less and take up less space than the gear they replace, he said. They’re capable of a wider range of functions, including regulating power quality fluctuations, which can wreak havoc on data centers, and they can be used for multiple applications, unlike traditional equipment.

As for the cost, Baglino said prices for Heron Power’s electronics are competitive with those for traditional tech. “We’re not asking for any premium over the solutions they’re buying right now.”

Like DG Matrix and Resilient Power, Heron Power is targeting data centers, solar and battery farms, and dense EV charging sites for early adoption, since that’s a “fast-growing market with motivated customers,” Baglino said.

Heron Power’s Heron Link devices are designed to handle typical utility distribution substation voltages of 34.5 kilovolts and to deliver 600-volt direct current. That higher-than-typical voltage aligns with the latest data center power architectures being pursued by major AI players such as Nvidia.

“But we have every intention of bringing the benefits of solid-state transformers to the AC-to-AC world,” he said, referring to the need for transformers to step voltage up and down without converting it to direct current. “A single SST can decouple faults, it can do power factor control, it can do voltage regulation, frequency regulation, all this monitoring and control of the power flow that utilities don’t have with passive transformers.”

While these are all useful capabilities, utilities are not eager adopters of novel technologies. Over the previous decade, companies that have built power electronics for utility distribution grids have closed up shop or have been acquired and fallen from public view.

But the combination of technical improvements and growing grid pressures may make this decade different. “Once we prove the technology is performing well” for solar farms and data centers, Baglino said, “we can go back to utilities.”

Before temperatures plunged to the teens in the wee hours of Feb. 2 in North Carolina, Duke Energy pleaded with customers like me to conserve.

Since electricity supplies would be strained, the utility said in a blanket email, we could help avoid planned blackouts by lowering our thermostats and perhaps putting on a sweater. I got a text, too, asking me to cut back on “nonessential energy use.” In other words: Embrace my inner Jimmy Carter.

The missives worked, in that Duke didn’t have to schedule outages around the state, but they also provoked resentment. At public hearings, some complained that large customers like data centers probably didn’t get the same appeal. On social media, I saw at least one energy policy wonk contend that the utility should be paying customers — not just asking them nicely — to reduce their energy use.

But it turns out that Duke also does that. I should know: Late last year, I joined the throng of Tar Heels who let the company remotely adjust our smart thermostats by a few degrees when needed in exchange for a credit on our bills. It’s just one example of the sort of demand-response program that clean energy advocates say should be expanded not just in North Carolina but also nationwide, as climate change leads to more frequent extreme weather that taxes electricity supplies.

While broad solicitations like the one I received on Feb. 1 can help relieve stress on the grid when every watt counts, paying customers to enroll in ongoing programs can have a more substantial effect. Plus, they offer some much-needed utility-bill relief for households dealing with skyrocketing energy costs in North Carolina and beyond.

A version of the incentive program I participate in has been around for nearly two decades, after a 2007 law required Duke to invest more in energy efficiency. Long an option in the summer for those with central air conditioning, the scheme was recently extended into the winter. Around 500,000 customers are enrolled in the warm months, Duke says, and some 66,000 are signed up in the cold months. (Participation is lower in the winter partly because many customers heat their homes with gas rather than electricity, per the utility.)

Duke hasn’t yet analyzed the precise effectiveness of this one residential incentive program during this year’s unusually frigid temperatures. But it says the combination of this household initiative, similar ones for business customers, and the mass conservation request all made a difference.

“The collective efforts of customers in our demand response programs and those who voluntarily reduced their energy use made a substantial impact during the stretch of extreme cold and unusually high energy demand,” spokesperson Jeff Brooks said in an email. “Across our Carolinas service areas, customers helped reduce demand on the grid by contributing hundreds of megawatts of electric load reduction.”

Hundreds of megawatts is no small matter. It’s the equivalent of the grid getting an additional small gas-fired power plant — but without the associated pollution or cost.

For consumers, there were clear upsides, too.

In Raleigh, where I live, the scheme is called EnergyWise. In other parts of Duke’s territory, it’s called Power Manager. Everywhere, the idea is the same: Customers with electric heat and thermostats connected to the internet get a $150 credit for enrolling, then $50 a year after that, plus whatever money we save by using a little less heat than we might otherwise. It’s not a staggering amount, but since the average Duke household in North Carolina spends about $154 a month on electricity, it’s not nothing, either.

For my part, the savings have been meaningful. I live in a small house powered partly by solar panels, so I’m not a prototypical Duke customer. But since joining the program in early December, I’ve paid the utility all of $6.45, thanks to the sign-up incentive. (My bill due in March, to be fair, is close to $130.) With Duke proposing rate increases of 15% in the coming years — and a 2025 law requiring households to shoulder more of the burden when the company buys power from outside the state — I’ll take the extra dollars where I can.

“Active savings events,” whereby Duke lowers my temperature setting a few degrees for one or two hours, happen a few times a month, per the company, or not at all if the weather is mild. A message on my physical thermostat, and on the phone app that controls it, tells me when an event is underway. I can opt out at any time by changing the temperature as I see fit.

A Gen Xer, I grew up in a household where only one person — my father, born in the throes of the Great Depression — could control the thermostat. His rule was kind but firm, with winter settings that never exceeded the high 60s. Sometimes he would cheerfully encourage an extra layer and start a fire. At night, he always set the temperature much lower.

Perhaps that upbringing, together with my career as an energy reporter, explain why I’ve felt the need to override a savings event only once so far. It wasn’t to raise the temperature but to lower it during the recent cold snap: I woke up in the middle of the night and realized I’d accidentally set the thermostat higher than normal. While Duke’s system had adjusted the heat down a few degrees, I wanted it to be colder still — a little bit for the planet, a little bit for bedtime coziness, but mostly for my wallet.

Of course, plenty of people will balk at giving Duke — a monopoly that almost by definition breeds distrust — control over their thermostats. And I can surely see how the entreaty for households to voluntarily conserve left a bitter taste when the company was reporting sky-high profits.

But I suspect there are scores of people like me, who are happy to do their part and save a little money at the same time with basically no risk. As for the half million North Carolinians already enrolled in the program, I know one thing for sure: They aren’t all energy reporters with solar panels.

A correction was made on Feb. 19, 2026: This story originally misstated the date of the Duke Energy email as Feb. 2; it came on Feb. 1.

Five years ago, Winter Storm Uri brought the Texas power grid to its knees. Temperatures plunged across the state for nearly a week, power plants froze, natural gas supply lines failed, and the grid operator came within minutes of a total system collapse. More than 4 million Texans lost electricity, many for days. Over 200 people died. It was the worst infrastructure failure in modern Texas history.

In the years since, Texas has quietly built one of the largest renewable energy and battery storage fleets in the world. According to capacity data from the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, the state has added roughly 31 gigawatts of solar capacity and 17 GW of battery energy storage — enough to power millions of homes. Over the same period, the legislature mandated weatherization of power plants and natural gas infrastructure, ERCOT improved its operational procedures, and new market mechanisms were introduced to better coordinate solar and storage.

The results speak for themselves. Since Uri, the Texas grid has faced three major winter storms that each set new all-time winter peak demand records. In every case, the grid held. No rolling blackouts. No load shedding. No emergency curtailments. Demand kept climbing, and the grid kept delivering.

This track record matters because a prominent Texas think tank, the Texas Public Policy Foundation, has published a widely circulated analysis arguing that ERCOT’s reliance on solar and battery storage is making the grid less reliable in winter. The analysis is authored by Brent Bennett and uses real ERCOT data. But as this article will show, Bennett’s own numbers contradict his conclusions — and the actual performance of the grid over the past five years contradicts them even more decisively.

The following chart I worked up offers a quick summary: Texas’ reliability has increased dramatically in recent years in direct proportion to the renewables and battery storage it has added.

The above data tells the story. At the time of Uri, ERCOT had roughly 5 GW of solar and less than 1 GW of battery storage. When Winter Storm Elliott arrived in December 2022, it had 14 GW of solar and 2 GW of storage. By Winter Storm Heather, in January 2024: 22 GW and 4 GW. By Winter Storm Kingston, in February 2025: 30 GW and 9 GW. And now, as we pass the fifth anniversary of Uri: approximately 35 GW of solar and 15 GW of battery storage.

During each of these storms, peak winter demand set a new record — climbing from 74,525 MW during Elliott to 78,349 MW during Heather to 80,525 MW during Kingston. Just three weeks ago, the grid sailed through another major winter storm with over 11,000 MW of operating reserves and ERCOT said it did “not anticipate any reliability issues on the statewide electric grid.”

In none of these events did ERCOT order load shedding. This is the track record that Bennett’s analysis asks you to ignore.

Now let’s turn to Bennett’s projected numbers for 2030. His Figure 1 posits that ERCOT could have 103,802 MW of firm output against a speculative peak demand of 110,000 MW — his estimate, not ERCOT’s. That’s a gap of roughly 6 GW. His projected battery fleet by 2030? Forty-three gigawatts.

Read that again: a 6-GW shortfall covered by 43 GW of batteries.

Bennett’s response to this rather obvious mismatch is to reframe the question entirely. Instead of asking whether batteries can cover peak demand windows — which is what they’re designed to do — he converts the entire battery fleet into a single energy metric: 77 GWh, which he says is “equivalent to running a single 1 GW thermal power plant for the duration of this three-day storm.” It’s a striking comparison. It’s also irrelevant to how batteries actually operate in ERCOT.

Nobody designs, operates, or dispatches battery storage as a 72-hour baseload resource. Batteries are designed to shave peaks, provide rapid frequency response, and bridge the morning and evening demand ramps when solar output is low. A 43-GW battery fleet can inject enormous amounts of power during exactly the narrow peak windows that Bennett’s own Figure 2 identifies as the problem periods. During Winter Storm Heather, ERCOT’s post-storm analysis confirmed that batteries were “partially supplementing the lack of solar generation available” during the coldest pre-sunrise hours — the exact scenario Bennett says they can’t handle.

Perhaps the most revealing aspect of Bennett’s analysis is what he doesn’t discuss: the massive existing fleet of gas, coal, and nuclear generation that forms ERCOT’s backbone. He projects 103,802 MW of firm winter output in 2030. That fleet — overwhelmingly fossil and nuclear — carries the grid through the vast majority of every storm hour in his model. The assumed thermal outage rate is only 12% — a figure drawn from ERCOT’s reliability assessments — meaning 88% of the thermal fleet performs through the modeled storm.

Bennett constructs a scenario in which batteries fail by defining success as continuous 72-hour discharge, while simultaneously taking for granted the thermal fleet of 80-plus GW that keeps the lights on during the bulk of his modeled event. The batteries aren’t replacing that fleet. They’re supplementing it during the peak demand windows that the thermal fleet alone can’t quite cover — which is precisely the role that ERCOT’s system planning envisions for them.

The contrast between Bennett’s theoretical model and actual ERCOT performance is stark. During Winter Storm Elliott, solar contributed roughly 8 GW at peak, and real-time prices dropped from over $3,000/MWh to under $100 within 90 minutes of sunrise. During Heather, large flexible loads curtailed voluntarily, demonstrating the demand-side response that Bennett barely acknowledges. ERCOT CEO Pablo Vegas has specifically identified the growth in battery capacity as “perhaps the most significant factor affecting grid stability,” while University of Texas energy professor Michael Webber credited “significant investments in more solar and more batteries and demand response” as key factors in the grid’s most recent winter storm performance.

None of these experts are claiming the grid faces zero risk. ERCOT’s probabilistic risk assessment, as reported in NERC’s winter reliability assessment, puts the chance of controlled load shed this winter at about 1.8% — low, but not zero. The question is whether Bennett’s framework for evaluating that risk is sound, and on that point, the data he himself relies on says no.

Bennett’s piece concludes that ERCOT needs “market design changes that redirect revenue away from wind and solar and toward resources that can work in all types of weather conditions.” That’s a policy preference dressed up as an engineering conclusion. His own data doesn’t support it.

What his data actually shows is that ERCOT has a manageable peak-demand gap that battery storage is well positioned to address, supplemented by a massive thermal fleet that provides the overwhelming majority of firm capacity during winter events. The December 2025 launch of ERCOT’s Real-Time Co-optimization Plus Batteries (RTC+B) market is specifically designed to optimize exactly this kind of coordination — dispatching storage where and when it creates the most grid value.

The real question isn’t whether batteries can run for 72 hours straight. No one is asking them to. The question is whether the combination of 100-plus GW of firm thermal capacity, a rapidly growing battery fleet, improving demand-response capabilities, and better weatherization standards can keep the lights on during winter storms. The last five years of actual performance — including three consecutive record-breaking winter peaks — provide a clear answer.

Bennett’s analysis works only if you accept his premise that battery storage should be evaluated as a baseload replacement rather than what it actually is: a fast-dispatching, peak-shaving complement to the thermal fleet, which helps dramatically in firming up renewables like wind and solar. Reject that premise, and his crisis narrative dissolves into the numbers he himself provides.

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the Week” column.

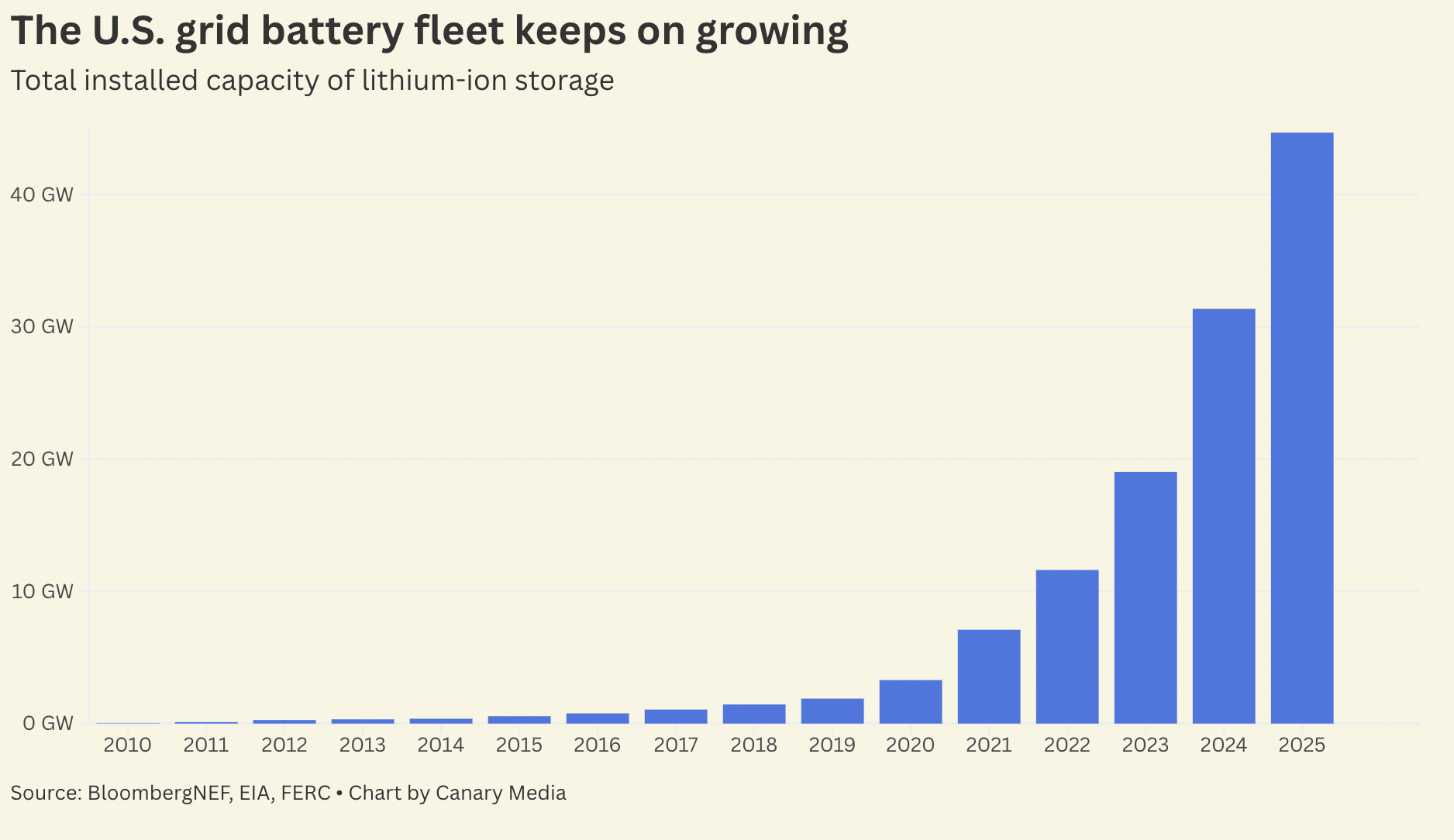

It’s official: Grid batteries broke another record.

More than 13 gigawatts of energy storage was installed across the U.S. last year, per a new report from the Business Council for Sustainable Energy and BloombergNEF. That’s up from the roughly 12 GW installed in 2024.

It’s the latest reminder of the meteoric rise of battery storage, a quick-to-deploy technology that’s key to cutting emissions from the electricity system. Storage enables the grid to bank electricity when it’s cheap and abundant — like when surplus solar is generated in the middle of a sunny day — and deploy it when prices are high and electrons are scarce.

Less than a decade ago, the sector was little more than an intriguing possibility. Energy storage in America mostly meant massive, decades-old pumped-hydro storage projects and a handful of small lithium-ion battery plants.

In 2017, only 500 megawatts of grid battery capacity was online in the U.S.; now, there are individual battery installations larger than 500 MW. Still, the sector had big expectations for itself back then: In 2017, the Energy Storage Association set a goal of reaching 35 GW of storage capacity by 2025.

Last year, the sector smashed that goal, hitting it in July and ending the year with nearly 45 GW of installed capacity.

Increasingly abundant solar power, rising energy demand, and declining battery costs have combined to propel the storage sector to these lofty heights. To date, most utility-scale batteries have been plugged into the grids of Texas and California, two solar-soaked states with radically different approaches to encouraging storage growth.

In the coming years, the storage sector has a smoother path to continued growth than do renewables.

Yes, it faces some challenges. Federal tax incentives are now contingent on compliance with strict but vague anti-China supply-chain rules. Developers also have to deal with tariffs and increasing local opposition.

But, unlike for solar and wind, tax credits for storage were spared in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act that President Donald Trump signed into law in July. Also unlike solar and wind, the battery industry has not yet attracted much explicit trash-talking from either Trump administration officials or Trump himself. Storage is also increasingly cheap and fast to build.

These facts, plus the urgent need for new sources of affordable energy as utility bills rise, have the storage industry poised for continued growth in the years to come.

Last Friday, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright held a press conference to talk about how the power grid didn’t collapse during late January’s Winter Storm Fern.

Some of the things he said were true. Others weren’t. It’s important to know the difference — especially as the Trump administration routinely uses misleading statements to justify decisions that make the power system dirtier, more expensive, and ultimately less reliable.

Wright, a former fossil gas–industry executive who has overseen the administration’s hard turn against clean energy, praised the efforts of utility workers who rallied from across the country and worked around the clock to restore power to more than 1 million people after ice and falling trees took out grid lines. That’s true, and good.

But the centerpiece of Wright’s nearly hourlong presentation was a series of charts, propped up on an easel, that served as a launchpad for the same kind of half-truths and obfuscations that have typified his approach to the job.

His pie charts showed the mix of electricity generation at the peak of wintertime demand across the eastern U.S. and in New England. There was a lot of fossil gas, a big slice of coal and of nuclear, and, in New England, a lot of oil — a key source of emergency generation in wintertime. Meanwhile, wind and solar power, the resources Wright called the “darlings” of the climate movement, were represented by very small slices.

In Wright’s view, these charts tell a story of waste and excess. People had to pay for the construction of all that renewable energy, and the poles and wires required to carry it, only for that power to disappear when the grid needed it most.

Here’s how he put it: “If you can add reliable power at peak demand time, you’re additive to the grid. If you can’t, you’re just … a cost center. You’re not actually helpful for the grid.”

This is a gross oversimplification of the complex ways that different types of power add value to the grid. As Wright well knows, people don’t need electricity on just the hottest or coldest days. They need it every day, all 8,760 hours of the year. And how that power is generated on a daily basis matters just as much as how it gets produced in extreme circumstances — for people’s wallets, their health, and the planet.

The vast majority of the time, wind and solar — and energy storage — reliably provide electricity to the grid. During the first 10 months of 2025, the U.S. got nearly one-fifth of its electricity from these sources.

Why is that? Because the electricity that renewables provide is cheap and plentiful. Nowadays, it is often less expensive than gas-fired power. And renewables are certainly much cheaper than coal power, even as Wright’s Department of Energy has spent the last year propping up the dirty fossil fuel at great cost to consumers.

For the past two years, solar, wind, and storage have made up more than 90% of the new electricity capacity being added in the U.S. — and around the world. And we will need to keep up that pace for the U.S. to meet growing power demand from data centers and electrification without causing already rising electricity costs to soar further.

But Wright casts cheap, clean power as mere empty calories that steal market share from coal, gas, and nuclear power. Energy supplied only when “the weather is mild, when the sun shines or the wind blows, doesn’t add anything to the capacity of our electricity grid,” he said. “It just means we send subsidy checks to those generators, and we tell the other generators, ‘Turn down.’”

Here, Wright mischaracterizes how utilities and grid operators dispatch power plants. Wind and solar often “turn down” when they’re generating more power than the grid needs. But fossil-fueled power plants stop generating when their power is too expensive to compete with what wind and solar generators are offering — market forces in action.

It’s worth mentioning, too, that utilities and grid operators are well aware that wind and solar are weather-dependent and don’t produce all the time. These experts constantly assess the availability of all resources — not just renewables — and plan accordingly.

Wright also neglected to say that fossil fuels themselves can fail during winter storms — and often in less predictable and more harmful ways than when the sun sets or the wind dies down.

That’s what happened during Winter Storm Uri in 2021. That storm swept over the U.S. Southeast — and in particular, Texas — bringing subzero temperatures that froze wellheads and restricted the flow of gas to power plants, which were experiencing their own weather-related failures. The result was catastrophic: More than 200 people died and roughly 4.5 million homes and businesses lost power. Similar gas-system freeze-ups drove winter blackouts across the Southeast in 2022 and during the 2014 “polar vortex” in the Northeast.

During Winter Storm Fern, it was a different story: Generator failures did not force utilities and grid operators to shut off power. One likely reason is that, in the years since Uri, regulators have imposed winterization requirements on owners of gas power plants in Texas and other parts of the country, though just how effective those interventions were is not yet clear.

Another probable factor contributing to the grid’s resilience this time around was having a better overall mix of resources. Energy experts agree that portfolios of mutually reinforcing resources are the key to grid reliability. In the Lone Star State, solar and battery storage have surged in recent years. Texas’ grid weathered this January’s cold snap, experts say, because it had an array of fuel sources on hand.

But of course, Wright didn’t acknowledge any of that. He simply railed against renewables, painting them as leeches on the power system.

Fossil-fueled power plants remain vital to the U.S. grid, whether they’re designed to run around the clock or only during emergencies, as is the case for New England’s oil-burning generators — one of the grid’s costliest resources, precisely because they run so infrequently. But renewables are vital, too. In New England, the gigawatts of offshore wind being built from Connecticut to Maine that have been under attack since the first day of the second Trump administration are also one of the most valuable winter resources for the region.

The DOE’s job is not to take a snapshot of the worst 15 minutes of the year and use it to justify policies that freeze in place that exact mix of grid resources. Instead, it’s to assess and manage the grid’s evolving technical, economic, environmental, and climatic realities, and to foster newer, better resources to replace those that aren’t keeping up.

The more Wright pretends otherwise, and uses half-truths to force fossil fuels onto a system that would be better served by cheaper and cleaner alternatives, the worse off we’ll all be.

Startup NineDot Energy just raised $431 million to build batteries in New York City’s vacant nooks and crannies — an endeavor that will help the metropolis fend off looming electricity shortages.

The debt financing announced Monday will support the Brooklyn firm’s plan to develop 28 battery projects totaling 494 megawatt-hours of energy storage capacity over the next two years. NineDot estimates that’s enough storage to meet the peak energy needs of about 100,000 households.

NineDot is one of several companies deploying “community battery systems” — grid-tied energy storage installations that can fit into roughly an acre of land or less — in New York City. These systems sop up excess energy from the grid when power is abundant and send it back when demand is high, like on hot summer afternoons when millions of air conditioners crank up. Bigger batteries may be able to store more energy, but community-scale systems can be more realistic to quickly deploy in über-dense places.

The decade-old startup’s latest round of construction finance, led by Natixis Corporate & Investment Banking, brings its total funding to just over $1 billion, said David Arfin, NineDot’s CEO and co-founder.

NineDot already has seven projects operating — including a 12-megawatt-hour battery and solar installation at a former parking lot in the Bronx and a 20-megawatt-hour battery system in Staten Island — or in advanced stages of construction in New York City, he said. By 2028, it plans to have 37 community storage systems with a combined capacity of 1.6 gigawatt-hours up and running across the five boroughs, he said.

It isn’t easy to find spots to build batteries in New York City, said Adam Cohen, NineDot’s chief technology officer and co-founder. It can be even harder to find space on Con Edison’s power grid to connect them, he said.

But the utility is under mounting pressure to expand its energy storage capacity — and that’s driving companies like NineDot to seek out vacant or underused lots in the country’s densest urban environment.

New York law sets a statewide goal of 70% renewable electricity by 2030, and state policy calls for building 6 gigawatts of energy storage by 2030. Upstate New York has plenty of land for utility-scale wind, solar, and battery farms. But downstate New York and New York City are where power demand is greatest and the generation mix is the dirtiest — and there’s not yet enough transmission grid capacity to solve those problems with clean power from the north, Cohen said.

Meanwhile, the New York City area faces an energy crunch as power demand surges and aging fossil-fueled plants in the boroughs prepare to shutter. In October, the state’s grid operator warned that New York City and Long Island might face “reliability violations” as soon as this summer.

Late last year, state regulators ordered Con Edison to seek out “a broad array of potential non-emitting solutions” that could quickly bolster reliability.

“You could solve that with new transmission,” Cohen said — except that’s hard to build. The Champlain Hudson Power Express, a major transmission line from Canada to New York City, is nearing completion and scheduled to start delivering hydropower and wind power in May. But another major transmission line being planned to carry power into the city was canceled in 2024.

Another option is “keeping dirty peaker plants online,” Cohen said. But the fossil-fueled plants that New York City relies on to serve its peak loads are expensive to operate and emit health-harming air pollutants, largely in low-income communities and communities of color.

That’s why state regulators’ order to Con Edison calls for “non-emitting solutions, prioritizing cost-effectiveness and ease of deployment, and minimizing impacts to disadvantaged communities.”

Batteries fit that bill, say proponents of the tech. William Acker, executive director of the New York Battery and Energy Storage Technology Consortium, noted that the utility’s initial report to regulators in January identified a roughly 125-megawatt shortfall for about three hours during peak summer demand starting in 2032. This is “well within the range of the energy storage we expect to be deployed,” he said.

“That’s changing how the state is looking at energy storage deployment in New York City,” Acker said. “It’s one of the most cost-effective ways to address this reliability challenge.”

New York state has struggled to meet its targets for utility-scale clean energy, with supply chain disruptions and rising interest rates undermining the financial prospects for big wind and solar farms. It’s also faced challenges in getting large-scale battery projects up and running, largely because of problematic contract structures that crimped project financing.

But smaller community battery projects, like NineDot’s, have an advantage on that front: They can access the state’s incentives designed to encourage distributed energy resources that deliver power when and where the grid needs it the most. These incentives offer far steadier and more predictable revenue streams than those set up for the state’s larger-scale utility programs, Arfin said.

Community battery projects are also eligible to feed into New York’s Statewide Solar for All program, which provides a portion of revenues from community solar and storage projects to utility customers in disadvantaged communities who are enrolled in energy-affordability programs. NineDot forecasts that the projects it has committed to Statewide Solar for All will deliver more than $60 million in energy credits over the coming decade.

NineDot’s strategy of putting batteries on vacant or underutilized lots is one of several approaches being taken to add energy storage to the New York City grid. For example, Con Edison has deployed batteries at its substations and worked with companies installing them at EV charging stations and electric school bus depots. And some New York City businesses are using small plug-in batteries to cushion their draw on grid power during hours of peak demand.

Meanwhile, larger-scale projects like 174 Power Global’s 400-megawatt-hour battery in Queens are starting to get built, and energy developers, including Summit Ridge Energy and Convergent Energy and Power, have community battery projects underway.

But batteries in the Big Apple aren’t always getting a warm reception from their neighbors. Public opposition, spurred by a spate of grid battery fires, has quashed several projects in Staten Island and has led to an ongoing moratorium on their construction in the Long Island town of Oyster Bay. New York City mayoral candidate Curtis Sliwa railed against battery projects in the waning days of his campaign last year, calling them “mini-Chernobyls.”

But Cohen noted that the Fire Department of New York has spent years developing grid-battery safety rules that may be the most comprehensive in the country. “The FDNY is the global gold standard for approving battery storage technology and sites,” he said. “It’s cumbersome — but it’s trusted and thorough.”

A decade ago, North Carolina boasted more solar power than any other state in the country but California — a distinction owed to scores of large projects built under a suite of clean energy–friendly policies that the Tar Heel State has since repealed or amended.

Now, many of those solar farms are staring down the end of their initial agreements with Duke Energy, the state’s predominant utility. But under a new proposal before North Carolina regulators, project owners could lock in favorable long-term renewals pending one main condition: They have to add batteries.

The scheme was proffered by Duke and is backed by clean energy businesses and advocates. If it’s green-lit by the North Carolina Utilities Commission, it would represent the first systematic move toward “repowering” large-scale solar facilities in the state. The potential is enormous: Contracts expiring in the next five years total 1.9 gigawatts — an amount equal to more than a quarter of North Carolina’s entire utility-scale solar fleet.

Since battery storage will benefit from federal tax credits with few strings attached for at least another six years, and Duke faces daunting power demands from coming data centers and other large electricity users, this form of repowering could support reliability and affordability. In large swaths of rural North Carolina, extending the life of these older projects also makes more sense than decommissioning them.

“Adding batteries to a system that’s already out there makes it immensely more valuable to the grid,” said Steve Kalland, executive director of the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center. “In North Carolina, that’s going to be significant.”

More so than its ample sunshine or abundant open space, state policy propelled North Carolina to become a national solar leader back in 2016.

A decades-old state tax credit supplemented federal incentives, and in 2007, lawmakers adopted a modest but meaningful renewable energy requirement. But perhaps most important was the state’s implementation of a federal law designed to encourage small power producers independent of utility monopolies. North Carolina’s rules under the Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act, or PURPA, were among the most favorable in the country, with standard offer, 15-year contracts available for projects with up to 5 megawatts of capacity.

This cocktail of rules and mandates caused PURPA-qualified solar projects to soar, with over 450 large-scale developments coming online in the state from 2010 to 2017, according to the nonprofit North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, with a capacity of over 3.3 gigawatts.

But by 2017, Duke was on pace to easily meet the clean energy mandate, and Republican state lawmakers had repealed the tax incentive. What’s more, the utility said the surge in solar was creating interconnection bottlenecks and the need for expensive grid upgrades.

So the company helped draft a new state law that year meant to clear the backlog and move most new solar into a competitive procurement process. The standard offer contracts under PURPA survived but were reduced to 10 years for projects with up to 1 megawatt.

In part due to the PURPA changes, annual solar installations in the state have slowed, dropping from a peak of 985 megawatts in 2017 to an average of just under 500 megawatts in the years that followed.

How much should data centers pay for the massive amounts of new power infrastructure they require? Wisconsin’s largest utility, We Energies, has offered its answer to that question in what is the first major proposal before state regulators on the issue.

Under the proposal, currently open for public comment, data centers would pay most or all of the price to construct new power plants or renewables needed to serve them, and the utility says the benefits that other customers receive would outweigh any costs they shoulder for building and running this new generation.

But environmental and consumer advocates fear the utility’s plan will actually saddle customers with payments for generation, including polluting natural gas plants, that wouldn’t otherwise be needed.

States nationwide face similar dilemmas around data centers’ energy use. But who pays for the new power plants and transmission is an especially controversial question in Wisconsin and other “vertically integrated” energy markets, where utilities charge their customers for the investments they make in such infrastructure — with a profit, called “rate of return,” baked in. In states with competitive energy markets, like Illinois, by contrast, utilities buy power on the open market and don’t make a rate of return on building generation.

Although seven big data-center projects are underway in Wisconsin, the state has no laws governing how the computing facilities get their power. Lawmakers in the Republican-controlled state Legislature are debating two bills this session. The Assembly passed the GOP-backed proposal on Jan. 20, which, even if it makes it through the Senate, is unlikely to get Democratic Gov. Tony Evers’ signature. According to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, a spokesperson for Evers said on Jan. 14 that “the one thing environmentalists, labor, utilities, and data center companies can all agree on right now is how bad Republican lawmakers’ data center bill is.” Until a measure is passed, individual decisions by the state Public Service Commission will determine how utilities supply energy to data centers.

The We Energies case is high stakes because two data centers proposed in the utility’s southeast Wisconsin territory promise to double its total demand. One of those facilities is a Microsoft complex that the tech giant says will be “the world’s most powerful AI datacenter.”

The utility’s proposal could also be precedent-setting as other Wisconsin utilities plan for data centers, said Bryan Rogers, environmental justice director for the Milwaukee community organization Walnut Way Conservation Corp.

“As goes We Energies,” Rogers said, “so goes the rest of the state.”

We Energies’ proposal — first filed last spring — would let data centers choose between two options for paying for new generation infrastructure to ensure the utility has enough capacity to meet grid operator requirements that the added electricity demand doesn’t interfere with reliability.

In both cases, the utility will acquire that capacity through “bespoke resources” built specifically for the data center. The computing facilities technically would not get their energy directly from these power plants or renewables but rather from We Energies at market prices.

Under the first option, called “full benefits,” data centers would pay the full price of constructing, maintaining, and operating the new generation, and would cover the profit guaranteed to We Energies. The data centers would also get revenue from the sale of the electricity on the market as well as from renewable energy credits for solar and wind arrays; renewable energy credits are basically certificates that can be sold to other entities looking to meet sustainability goals.

The second option, called “capacity only,” would have data centers paying 75% of the cost of building the generation. Other customers would pick up the tab for the remaining 25% of the construction and pay for fuel and other costs. In this case, both data centers and other customers would pay for the profit guaranteed to We Energies as part of the project, though the data centers would pay a different — and possibly lower — rate than other customers.

Developers of both data centers being built in We Energies’ territory support the utility’s proposal, saying in testimony that it will help them get online faster and sufficiently protect other customers from unfair costs.

Consumer and environmental advocacy groups, however, are pushing back on the capacity-only option, arguing that it is unfair to make regular customers pay a quarter of the price for building new generation that might not have been necessary without data centers in the picture.

“Nobody asked for this,” said Rogers of Walnut Way. The Sierra Club told regulators to scrap the capacity-only option. The advocacy group Clean Wisconsin similarly opposes that option, as noted in testimony to regulators.

But We Energies says everyone will benefit from building more power sources.

“These capacity-only plants will serve all of our customers, especially on the hottest and coldest days of the year,” We Energies spokesperson Brendan Conway wrote in an email. “We expect that customers will receive benefits from these plants that exceed the costs that are proposed to be allocated to them.”

We Energies has offered no proof of this promise, according to testimony filed by the Wisconsin Industrial Energy Group, which represents factories and other large operations. The trade association’s energy adviser, Jeffry Pollock, told regulators that the utility’s own modeling of the capacity-only approach showed scenarios in which the costs borne by customers outweigh the benefits to them.

Clean energy is another sticking point. Clean Wisconsin and the Environmental Law and Policy Center want the utility’s plan to more explicitly encourage data centers to meet capacity requirements in part through their own on-site renewables, and to participate in demand-response programs. Customers enrolled in such programs agree to dial down energy use during moments of peak demand, reducing the need for as many new power plants.

“It’s really important to make sure that this tariff contemplates as much clean energy and avoids using as much energy as possible, so we can avoid that incremental fossil fuel build-out that would otherwise potentially be needed to meet this demand,” said Clean Wisconsin staff attorney Brett Korte.

And advocates want the utility to include smaller data centers in its proposal, which in its current form would apply only to data centers requiring 500 megawatts of power or more.

We Energies’ response to stakeholder testimony is due on Jan. 28, and the utility and regulators will also consider public comments that are being submitted. After that, the regulatory commission may hold hearings, and advocates can file additional briefs. Eventually, the utility will reach an agreement with commissioners on how to charge data centers.

Looming large over this debate is the mounting concern that the artificial-intelligence boom is a bubble. If that bubble pops, it could mean far less power demand from data centers than utilities currently expect.

In November, We Energies announced plans to build almost 3 gigawatts of natural gas plants, renewables, and battery storage. Conway said much of this new construction will be paid for by data centers as their bespoke resources.

But some worry that utility customers could be left paying too much for these investments if data centers don’t materialize or don’t use as much energy as predicted. Wisconsin consumers are already on the hook for almost $1 billion for “stranded assets,” mostly expensive coal plants that closed earlier than originally planned, as Wisconsin Watch recently tabulated.

“The reason we bring up the worst-case scenario is it’s not just theoretical,” said Tom Content, executive director of the Citizens Utility Board of Wisconsin, the state’s primary consumer advocacy organization. “There’s been so many headlines about the AI bubble. Will business plans change? Will new AI chips require data centers to use a lot less energy?”

We Energies’ proposal has data centers paying promised costs even if they go out of business or otherwise prematurely curtail their demand. But developers do not have to put up collateral for this purpose if they have a positive credit rating. That means if such data center companies went bankrupt or otherwise couldn’t meet their financial obligations, utility customers may end up paying the bill.

Steven Kihm, the Citizens Utility Board’s regulatory strategist and chief economist, gave examples of companies that had stellar credit until they didn’t, in testimony to regulators. The company that made BlackBerry handheld devices saw its stock skyrocket in the mid-2000s, only to lose most of its value with the rise of smartphones, he noted. Energy company Enron, meanwhile, had a top credit rating until a month before its 2001 collapse, Kihm warned. He advised regulators that data center developers should have to put up adequate collateral regardless of their credit rating.

The Wisconsin Industrial Energy Group echoed concerns about risk if data centers struggle financially.

“The unprecedented growth in capital spending will subject [We Energies] to elevated financial and credit risks,” Pollock told regulators. “Customers will ultimately provide the financial backstop if [the utility] is unable to fully enforce the terms” of its tariff.

Jeremy Fisher, Sierra Club’s principal adviser on climate and energy, equated the risk to co-signing “a loan on a mansion next door, with just the vague assurance that the neighbors will almost certainly be able to cover their loan.”