California lawmakers are considering two bills that would slash red tape for households looking to add certain types of clean tech.

Earlier this month, state Sen. Scott Wiener (D), whose district includes San Francisco, introduced legislation that would make it easier for individuals to adopt all-electric, superefficient heat pumps (SB 222) and plug-in solar panels (SB 868).

“The cost of energy is too high,” Wiener told Canary Media. “We want to lower people’s utility bills; we want people to be able to participate in the clean energy economy; and we want people to be able to take control of their energy future. And that’s what these bills do.”

The proposals come as Americans are in the grip of a worsening cost-of-living crisis — of which energy is a key driver.

Electricity costs have grown at about 2.5 times the pace of persistent inflation, and home heating costs are expected to surge this winter. In California, which has the second-highest electricity rates in the nation, the problem is particularly pressing.

Heat pumps and plug-in solar panels could help.

Heat pumps — air conditioners that also provide all-electric heat — are about two to five times as efficient as gas furnaces without those appliances’ planet-warming and health-harming pollution. Even in California, where gas is relatively inexpensive compared with electricity, a heat pump’s high efficiency can enable households to save on their energy bills, especially when tapping the sun for cheap, abundant power.

Enter portable, plug-and-play solar panels. These modest systems, which users can drape over balcony railings or prop up in backyards, allow renters, apartment dwellers, and others who can’t put panels on their roofs to harvest enough of the sun’s rays to power a fridge or a few small appliances for a fraction of the day. A connected battery can save solar energy for use at night.

The tech is booming in Europe. In Germany, for example, where people can order kits via Ikea, as many as 4 million households have hung up Balkonkraftwerke, or “balcony power plants.” There, households can cover as much as one-fifth of their energy needs using these systems.

In the U.S., an 800-watt unit for $1,099 can save a household as much as $450 annually in states with higher electricity prices like California, according to The Washington Post.

But unlike those in Germany, U.S. households typically need to apply for an interconnection agreement with their utility before they can install these systems — just as they would for adding a rooftop solar array. That process often requires fees, permits, and an inspection, and it can take weeks to months. Only one state allows residents to install plug-in solar without a utility’s permission: deep-red Utah.

Lawmakers elsewhere are now stampeding to make plug-in solar available to their constituents.

Besides Utah and now California, legislatures in more than a dozen states want to unleash the tech: Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington have all introduced bills, according to Cora Stryker, co-founder of plug-in solar nonprofit Bright Saver, which has been advising some states on their proposals. Based on conversations the organization has had with state representatives, Stryker said she expects a whopping half of U.S. states to introduce bills this year.

“We should empower people to use this technology,” Wiener said. “And right now, it’s too hard. The idea that you have to get an interconnection agreement with the utility to put … plug-in solar on your balcony — it makes no sense.”

Administrative hurdles are also holding back heat pumps.

“The current permitting process is difficult,” Aaron Gianni, president of Larratt Brothers Plumbing in San Francisco, told state policymakers on Jan. 6. “As a contractor dealing with more than 109 different building departments in the Bay Area, we must navigate the nuances of each: different inspectors, changing paperwork requirements, high fees, and strict setbacks [that] sometimes make installation impossible.”

The situation can be even worse when a customer lives in a unit governed by a homeowners association, Gianni said. “Many HOAs have outright prevented new electric equipment from being installed.”

Wiener, who’s running for U.S. Rep. Nancy Pelosi’s seat and boasts a tongue-in-cheek MAGA fan club, put it bluntly. Permitting in some cities “is way too lengthy and onerous and expensive.”

“The [heat-pump] bill creates a streamlined path to be able to get a quick, automatic permit,” he explained. It would also loosen restrictions on equipment placement, cap permit fees at $200, and make it illegal to ban heat pumps.

Wiener’s heat-pump legislation, which has some industry detractors as well as grassroots supporters, has already passed out of the state Senate’s housing and local-government committees.

The plug-in solar bill has yet to come up for any votes. Still, with energy affordability shaping up to be a decisive issue in the 2026 midterm elections, both proposals “have, I think, a real possibility of passing,” Wiener said.

“These technologies are a win-win-win, and enabling access to them is simply good government.”

The Double Island Volunteer Fire Department in Yancey County, North Carolina, is the beating heart of this remote community in the shadow of Mount Mitchell, about 50 miles northeast of Asheville. Once home to a schoolhouse that doubled as a church, the red-roofed building still hosts weddings, parties, and other events.

“It was built to serve as a community center,” said Dan Buchanan, whose family has lived in the area since 1747 and whose mother attended the school as a young girl. “A place to gather.”

Sixteen months ago, when Hurricane Helene hit this rugged corner of countryside with catastrophic floods, Double Island’s fire department was where locals turned for help.

“This is [our] ‘downtown,’” said Buchanan, who serves as the assistant fire chief. “In the wake of the storm, people were like, ‘Let’s get to the fire station.’ That was the goal of everybody.”

Fresh out of retirement and living back in his hometown to care for his ailing mother, Buchanan drew on his long career in emergency response to spring into action. With the station, powered by generators, serving as their command center, he and his neighbors gathered and distributed food, water, and other provisions to those in need. They hacked through downed limbs and sent out search teams.

“By the end of the fourth day, we had accounted for all the residents of the Double Island community,” Buchanan said. And while no one in the enclave died because of the hurricane, some suffered while they waited for medications like insulin.

A lack of drinking water and limited forms of communication were also huge obstacles. “When we finally got the roads cleared, and people could get in here, we were literally writing down our needs on a notepad and giving it to whomever, and then they would ferry supplies,” Buchanan said. “A carrier pigeon would have been nice.”

Helene was a “once in 10 lifetimes” storm, Buchanan said, with devastation he and the community hope to never see again. But more extreme weather events are all but certain thanks to climate change, and today Double Island is better prepared.

The station is equipped with a microgrid of 32 solar panels and a pair of four-hour batteries. The donated equipment will shave about $100 off the fire department’s monthly electric bill, meaningful savings for an organization with an annual operating budget of just $51,000.

When storms inevitably hit, felling trees and downing power lines, the self-sustaining microgrid can provide some electricity and an internet signal.

“We’ll have at least a way to run our radio equipment, run our well and basic lighting and refrigeration,” Buchanan said, adding that the latter was vital for medication. “It may not seem like much — but that’s the Willy Wonka golden ticket.”

Communication, he stressed, was key. “If you can’t communicate, you can’t get the help you need.”

The microgrid project, called a resilience hub, was made possible by a network of government and nonprofit groups that came together after Helene to help fire departments like Double Island and other community centers with long-term recovery. Now, a state grant program is injecting a burst of funds into their efforts. Using both public and private time, know-how, and money, the program aims to create a model for resilience that can be replicated nationwide.

“We aren’t only preparing for a disaster; we’re also helping utility diversification, cost savings, and normalization of the technology,” said Jamie Trowbridge, a senior program manager at Footprint Project, a leading nonprofit in the initiative. Those benefits aren’t unique to Yancey County, he said. “We’d like to see this be a pilot for us on what scalable microgrid technology could be across all of western North Carolina — and maybe the country.”

The Double Island experience was common in the immediate aftermath of Helene. Across the region, communities isolated by closed roads and mountainous terrain turned to their fire departments for help.

That’s part of how Kristin Stroup got involved in the resilience hub effort. Based in Black Mountain, a popular tourist destination 15 miles east of Asheville, Stroup helped start a corps of volunteers who gathered at the town’s visitor center. In coordination with an emergency operations center based at Black Mountain’s main fire station, she led over 200 volunteers in doing whatever they could, from cooking and doling out food to making the country roads passable.

“People [were] just driving around the town with chain saws,” said Stroup, today a senior manager in energy and climate resilience with the nonprofit Appalachian Voices. The weekend after Helene hit, she said, “Footprint rolled into town with a bunch of solar panels. I became an instant part of their family.”

With founders who cut their teeth in international aid, the New Orleans–based Footprint Project had teamed up with the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, Greentech Renewables Raleigh, and others to pool donations of batteries, solar panels, and other equipment to deploy microgrids to dozens of sites in the region before the end of 2024. From Lake Junaluska to Linville Falls, recipients included fire stations such as the one in Double Island and an art collective in West Asheville.

By February 2025, Footprint had hired Trowbridge and another staff person to work in the area permanently. Footprint continued to cycle microgrid equipment throughout the region from its base of operations in Mars Hill, a tiny college town 20 miles north of Asheville that was virtually untouched by Helene. It launched the WNC Free Store, which donates solar panels and other supplies to residents still far from recovery — like those living out of RVs and school buses after losing their homes.

From the outset, Footprint had a critical local ally in Sara Nichols, the energy and economic development manager at the Land of Sky Regional Council, a local government partnership encompassing four counties that stretch from Tennessee to South Carolina.

“A lot of the other organizations we saw come through in the same way Footprint did, most of them did not stay. They leverage resources to do really important work, and when that work feels done, they go home,” Nichols said. “The fact that Footprint is working thoughtfully to figure out how our recovery and resiliency can be taken care of — while also thinking about their own organizational strategic growth — means a lot to me. They’ve been incredible partners.”

To be sure, assistance and rebuilding in the region are ongoing, and many systemic inequities exacerbated by the storm can’t be solved with a solar panel. But the power is back on. The cell towers are functioning. The roads are open. Piles of debris, from fallen limbs to moldy furniture, have been cleared. In relief parlance, western North Carolina is beginning to see “blue skies.”

That’s why it’s all the more important that Footprint, Appalachian Voices, and other local collaborators haven’t let up in their efforts. The web of organizations involved is thick and, seemingly, ever expanding. Last fall, the network announced it was deploying five resilience hubs around the region, including the Double Island project and a permanent microgrid at a community center in Yancey County.

“These projects, driven by a small group of determined partners, have accelerated Appalachia’s long-term resilience and preparedness,” Invest Appalachia, another nonprofit partner, said in a news release.

Now, the local public-private effort is getting a boost from the state of North Carolina. Under the administration of Gov. Josh Stein, a Democrat who has made Helene recovery a centerpiece of his first-term agenda, the State Energy Office will deploy $5 million from the Biden-era Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to install up to 24 microgrids across six western counties impacted by Helene.

The money will also go to two mobile aid units for rural counties on either end of state — one in the east and one in the west. Dubbed “Beehives” by Footprint, these solar-powered portable units will be full of equipment that can be deployed to purify water, set up temporary microgrids, and otherwise respond to storms and extreme weather.

Expected recipients of the stationary microgrids could include first responders like the Double Island Fire Department and second responders like community centers. Peer-to-peer facilities and small businesses are also encouraged to apply.

Land of Sky and other stakeholders are choosing grantees on a rolling basis through next summer. There’s already been an inundation of applicants, and six grantees have been selected, including a community center about a dozen miles up the road from Double Island in Mitchell County. But organizers say they need more interest from outside the Land of Sky region, especially in Avery County, north of Yancey on the Tennessee border; and Rutherford County, east of Asheville, which includes Chimney Rock, a village that was infamously devastated by Helene and is slowly rebuilding.

Geographic distribution isn’t the only problem organizers have faced. Some entities — while undoubtedly deserving of assistance — aren’t appropriate for the government grant because they are located in areas at risk of future flooding.

“A battery underwater is not that useful,” Trowbridge said, “so if your site is in a floodplain, maybe this isn’t the right fit for you. But we definitely want you to know about the Beehive.”

Above all, organizers like Nichols, a passionate promoter of the Appalachian Region, are determined to ensure that the state’s effort is not the be-all and end-all of resilience.

“What we’re being tasked with as recipients of this money is to try and figure out how we make this a much bigger project,” she said. “That means we’ve brought in other partners like Invest Appalachia. We’ve been seeking other kinds of money. We’re using this state money to successfully build what could be a much more comprehensive resiliency hub model.”

She added that communities across the country — even if they think they’re safe from extreme weather and climate disaster — could take cues from the western North Carolina example.

“We were a place that was not supposed to get a storm,” Nichols said. “We were a climate haven.”

Offshore wind developers are back to building three major U.S. projects nearly a month after the Trump administration ordered them to pause construction.

Ørsted, Equinor, and Dominion Energy all got the green light from federal judges last week to resume work on their massive, multibillion-dollar wind farms off America’s east coast. The companies wasted no time restarting the installation of turbines, offshore substations, and other equipment — eager to make up for delays that had cost each of them millions of dollars a day and threatened to tank at least one project that is more than halfway complete.

The developers had been stuck in limbo since receiving the Dec. 22 suspension order from the U.S. Interior Department, which cited unspecified “reasons of national security” — a rationale that failed to convince federal judges as they weighed developers’ requests for relief. Two other in-progress projects remain mired by delays as they await hearings.

The late-December order was the culmination of the Trump administration’s yearlong assault on offshore wind, which has managed to freeze new development but has been less successful in stopping projects already underway. Most of the five projects are in advanced stages of construction and viewed as critical by grid planners for keeping electricity reliable and affordable. These offshore wind farms are likely the only ones that will get built nationwide in the coming years because of Trump’s interventions.

Dominion Energy, which is developing the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project, said it delivered the first batch of turbine components by ship to its leasing area off Virginia Beach, Virginia, last weekend and is now installing the first of its 176 turbines. All the turbine foundations are already in place for the $11.2 billion project, and the utility is working to start producing power in the first quarter of this year.

The wind farm is expected to supply 2.6 gigawatts of clean electricity to the grid when fully completed later this year — power that the region can’t afford to lose, according to the mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM Interconnection.

In a Jan. 13 court brief supporting Dominion Energy, PJM said the offshore wind project would help with the “acute need for new power generation to meet demand” in the 13-state region, much of which is being driven by the boom in AI data centers. “Further delay of the project will cause irreparable harm to the 67 million residents of this region that depend on continued reliable delivery of electricity,” according to PJM’s filing.

Meanwhile, off the coast of Rhode Island, Ørsted has resumed construction on the 704-megawatt Revolution Wind project, which was nearly 90% complete when the federal stop-work order came late last month. The Danish energy giant was hit with a similar order in August, which a federal judge lifted in September given the lack of any “factual findings” by the Trump administration.

Of Revolution Wind’s 65 wind turbines, 58 are already in place, as are the cables and substations needed to bring the power to shore. At the time of the December suspension, the $6.2 billion project had been expected to start generating power as soon as this month, according to Ørsted.

Equinor, which had also previously received a separate stop-work order, is back to work on its 810-MW Empire Wind project off the coast of Long Island, New York.

The developer recently warned that the $5 billion project, which is more than 60% complete, would likely face cancellation if work couldn’t resume by Jan. 16; it won a favorable ruling on Jan. 15. Molly Morris, president of Equinor Renewables America, said the project is using a heavy-lift vessel that is available at the project site only until February, The City reported. After that, Equinor wouldn’t have been able to lease the vessel for another year, creating untenable project delays.

A spokesperson for Equinor said the company now expects to complete work assigned to the vessel, which includes installing an offshore substation, following the injunction ruling.

Continuing construction on America’s offshore wind farms “is good news for stressed power grids on the East Coast,” Hillary Bright, executive director of the advocacy group Turn Forward, said in a statement last week. She added that if projects aren’t allowed to advance, the electricity system in the heavily populated region will be “more likely to experience reliability issues and see ratepayer bills soar.”

Americans’ utility bills are already climbing nationwide, owing in large part to the rising prices and constrained supplies of fossil gas. Residents in colder-climate states are especially feeling the squeeze this winter — though early data shows that existing offshore wind operations are helping reduce electricity costs in some places.

Vineyard Wind, a 800-MW wind farm off the coast of Massachusetts, has been sending power to the grid from 30 of its planned 62 turbines since last October. On Dec. 7, an especially chilly day, the project’s wind output helped displace a significant amount of fossil gas on the wholesale market, resulting in savings of more than $2 million for New England ratepayers over the course of the day, Amanda Barker, the clean energy program manager with Green Energy Consumers Alliance, said on a Jan. 21 press call.

Vineyard Wind is one of the two projects waiting to resume construction in the wake of Interior’s December suspension order. Its developers, Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, sued the federal government on Jan. 15, becoming the last of the affected firms to seek legal relief from the Trump administration’s attacks. Vineyard Wind is now 95% complete, with all but one of its turbines now hovering over the Atlantic Ocean.

The second stalled project, Sunrise Wind, is an Ørsted development off the coast of New York. The 924-MW wind farm is almost 50% complete and, before the stop-work order, was expected to come online in 2026. A court hearing for the development is scheduled for Feb. 2, and the delay is costing Ørsted millions of dollars in the meantime.

Overall, the court orders from last week represent a win for getting more electricity onto the grid during a time of rising demand — and another round of setbacks for Trump’s efforts to destroy the fledgling sector.

Still, it’s hard to say whether this marks the administration’s final attempt to stymie projects or whether more delay tactics are coming for America’s beleaguered offshore wind projects.

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the Week” column.

Clean energy manufacturing was on the upswing in the U.S. Then the first year of Trump 2.0 happened.

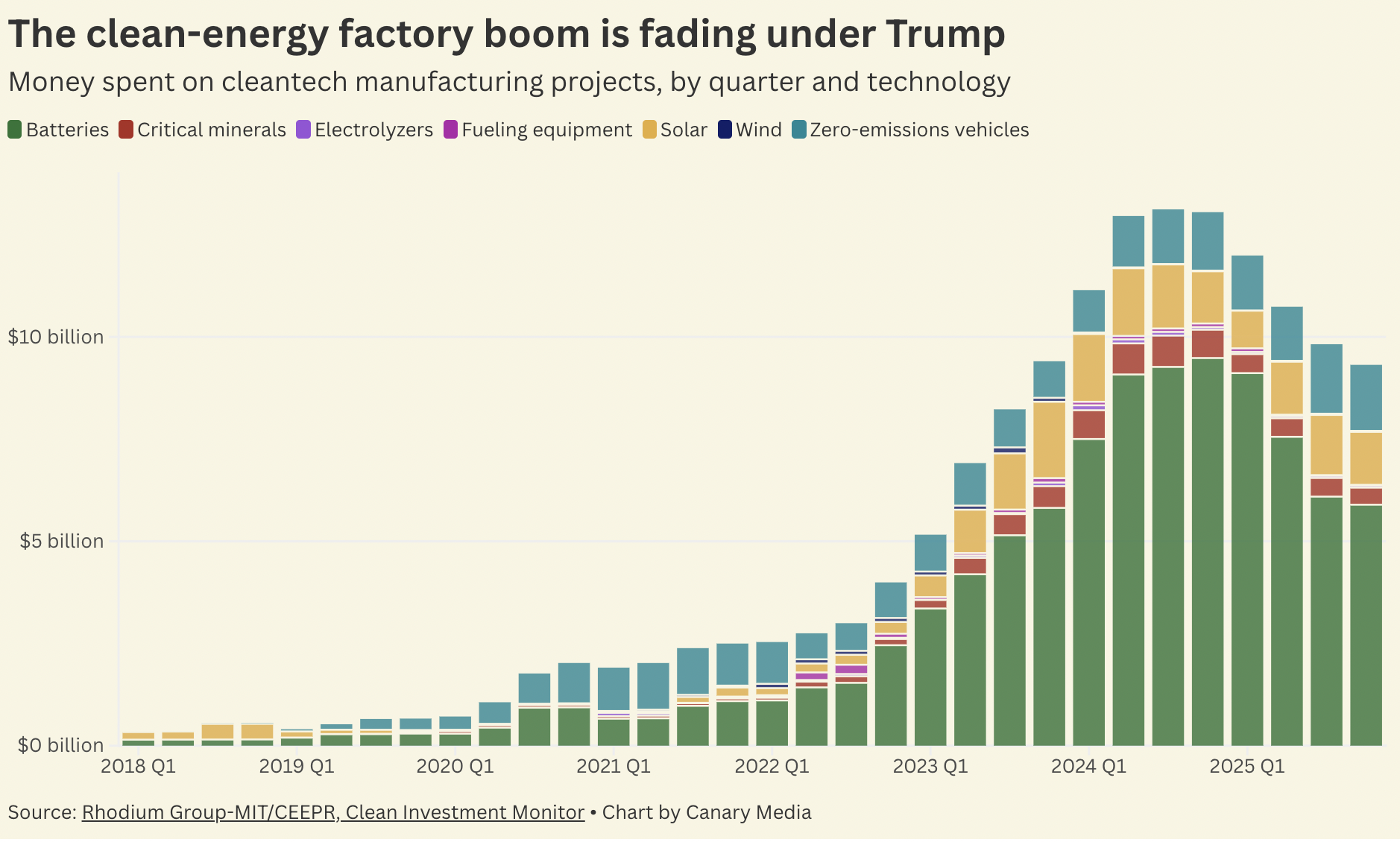

After years of increasing investment in factories to make batteries, electric vehicles, solar panels, and more — a surge prompted by the Inflation Reduction Act — the trend reversed under the Trump administration last year. Companies spent a total of $41.9 billion on cleantech manufacturing facilities in 2025, down from $50.3 billion the year before, per fresh figures from the Clean Investment Monitor, a joint project from Rhodium Group and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research.

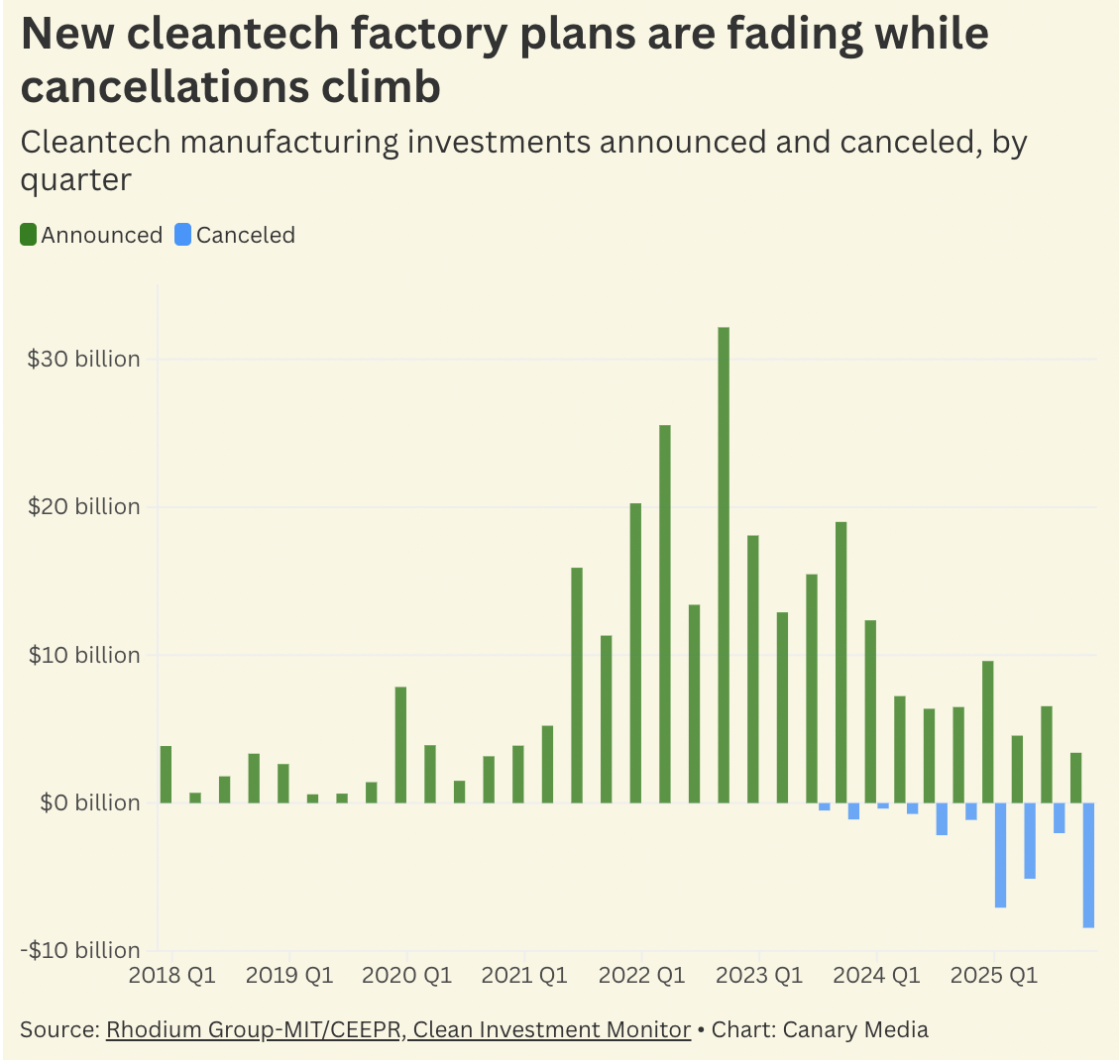

More concerning, however, is the fact that businesses are making fewer new plans to invest in cleantech factories — and a whole lot of companies are backing out of prior commitments.

Cancellations nearly matched factory announcements last year: Firms unveiled a total of $24.1 billion in new cleantech manufacturing projects, but scrapped $22.7 billion worth.

It’s a dramatic reversal. The Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act had spurred well over $100 billion in cleantech manufacturing commitments through incentives for both factories and their customers, be they families in the market for an EV or energy developers building a solar megaproject. The ensuing boom in cleantech factory construction created thousands of jobs and caused overall manufacturing investment to soar. Most of the investment was planned for areas represented by Republicans in Congress.

But last year, the Trump administration put strict stipulations on incentives for factories and repealed many of the tax credits that helped generate demand for American-made cleantech. It also showed an astonishing hostility to clean energy projects — namely offshore wind — and cast a general cloak of uncertainty over the entire economy.

To be fair, other potential factors are at play.

Some of the slowdown in cleantech factory investment could simply be the market maturing. Plenty of projects announced right after the Inflation Reduction Act might already be online, or close to it. Or it could be the result of the gravitational pull of the data center boom, which is attracting gobsmacking amounts of capital that could have otherwise financed more cleantech factories.

But either way, as the new data shows, the Trump administration has weakened the case for investing in expensive projects tied to clean energy. I’m willing to bet that the consequence will be more factory cancellations — and less investment — over this year, too.

This analysis and news roundup come from the Canary Media Weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it every Friday.

When it comes to state politics, 2026 is already in full swing. As legislators reconvene and new governors are sworn in, it’s becoming clear that leaders will focus on one energy issue in particular this year: affordability.

While last year’s elections didn’t bring any major changes to the White House or Congress, skyrocketing energy prices played an undeniable role in propelling Democrats to victory in state elections across the country.

Take a look at New Jersey, where Democratic Gov. Mikie Sherrill was sworn in this week after campaigning on a promise to lower power prices while building out clean energy. She took her first steps in that direction on Tuesday, signing executive orders to accelerate solar and storage development, consider freezing electricity rate hikes, and expand utility bill credits for customers.

Those credits will be funded in part by the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, an East Coast carbon market that saw good news with the inauguration of Virginia Democratic Gov. Abigail Spanberger this past weekend. Spanberger is already moving to rejoin RGGI, with an assist from the state’s Democratic-controlled legislature, after the previous Republican governor pulled Virginia out of the program back in 2023. On her first day in office, Spanberger also directed state agencies to find ways to curb energy and other household costs.

Affordability is sure to continue to dominate politics this year in Virginia, also known as the data center capital of the world, clean energy advocates recently told Canary Media’s Elizabeth Ouzts.

“Oftentimes, I go into a legislative session sort of just guessing what people are going to care about,” said Kendl Kobbervig of Clean Virginia. Not this year.“No. 1 is affordability, and second is data center reform.”

Massachusetts’ legislature shares that priority, reports Canary Media’s Sarah Shemkus. But even though the statehouse remains firmly in Democratic hands, lawmakers aren’t aligned on how to curb costs in the long term. Some are targeting volatile natural gas prices and the cost of replacing aging pipelines, others say clean energy and transmission construction are to blame, and still others are homing in on utility profit margins.

The reality is that the energy affordability crisis isn’t a problem with just electricity prices or natural gas prices; both are rising at rates higher than inflation across the country. And so it’s going to take strong, and perhaps creative, solutions to keep them in check.

Trump’s year of energy upheaval

It’s been a year since President Donald Trump took office for the second time, and there’s been no shortage of energy-industry shake-ups in the months since.

On his first day in office, Trump called out rising power demand and declared a national emergency on energy, which he has since used to justify keeping aging coal plants open long past their retirement dates.

His signature spending law, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, gutted tons of clean energy tax incentives. And that’s not to mention the administration’s decarbonization funding clawbacks, its holdup of renewables permitting, and its relentless attacks on the nation’s offshore wind industry.

Trump’s year-two agenda is already starting to take shape. Expect to see his administration order more coal plants to stay open, cancel additional clean energy funding, and throw up hurdles we can’t even imagine yet.

Geothermal is having a moment

As clean energy sources like offshore wind and solar struggle to snag a foothold in the new, post–tax credit world, geothermal proved this week that it still has the juice.

A wave of announcements from pioneering geothermal startups began on Wednesday, with Zanskar announcing it had raised $115 million in a Series C funding round. It’ll use the infusion to expand its AI software, which it used to uncover an untapped, invisible geothermal system in Nevada last year. Also on Wednesday, Sage Geosystems announced a more than $97 million Series B round, which will fund its first commercial-scale power generation project, slated to come online this year.

Fervo Energy completed the trifecta as it quietly filed for an IPO, Axios Pro reported on Thursday. The company hasn’t shared details about the filing, but said in December that it had raised about $1.5 billion so far in its quest to build a massive enhanced geothermal system in Utah.

Back to work: Wind farms off the coasts of New York, Rhode Island, and Virginia have all restarted construction after legal wins last week against the Trump administration’s stop-work order, though two other projects remain paused. (Canary Media)

Solar keeps surging: An Energy Information Administration analysis finds utility-scale solar is the fastest-growing power generation source in the U.S., and will continue to expand through 2027 as the shares of coal and gas in the energy mix decline. (EIA)

Rural resilience: North Carolina towns devastated by 2024’s Hurricane Helene are installing solar panels and batteries at community hubs to prepare for future disasters, with help from a program that could become a national model. (Canary Media)

Clean-steel influencers: A new report shows automakers buy at least 60% of the primary steel made in the U.S., which gives them leverage to push steelmakers to clean up production. (Canary Media)

Batteries at breakfast: A Brooklyn bagel shop is cutting its power bills by using suitcase-size batteries to run its oven and fridges when electricity demand is high. (Canary Media)

Renewables’ European win: Wind and solar generated 30% of the EU’s electricity last year, while fossil fuels provided 29%, marking the first time renewables have beaten coal, oil, and gas. (The Guardian)

Clawback consequences: Some communities that lost federal climate grants last year have sued to reclaim them, while others have had to move on from projects that would’ve helped them curb pollution and adverse health effects. (Grist)

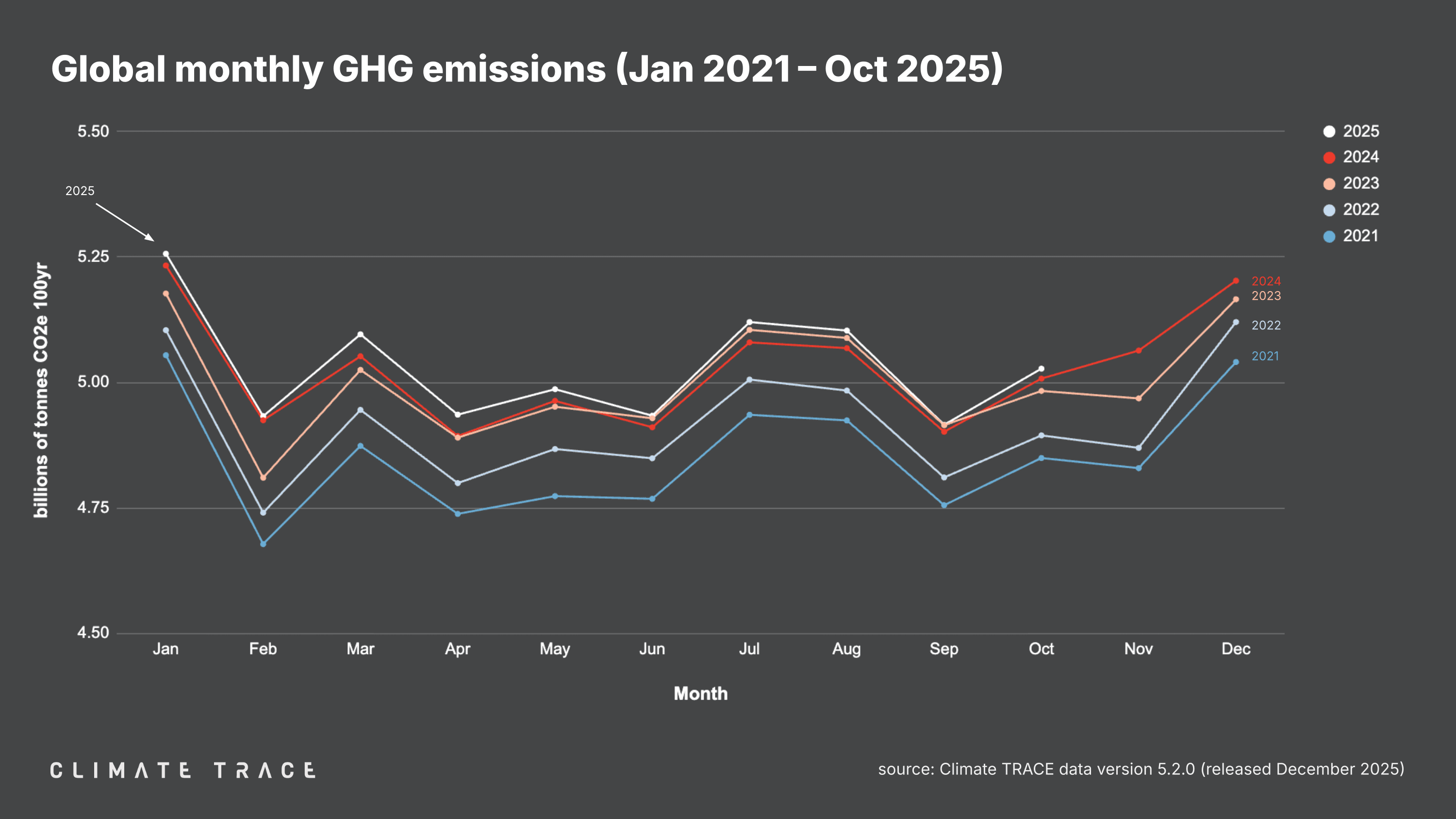

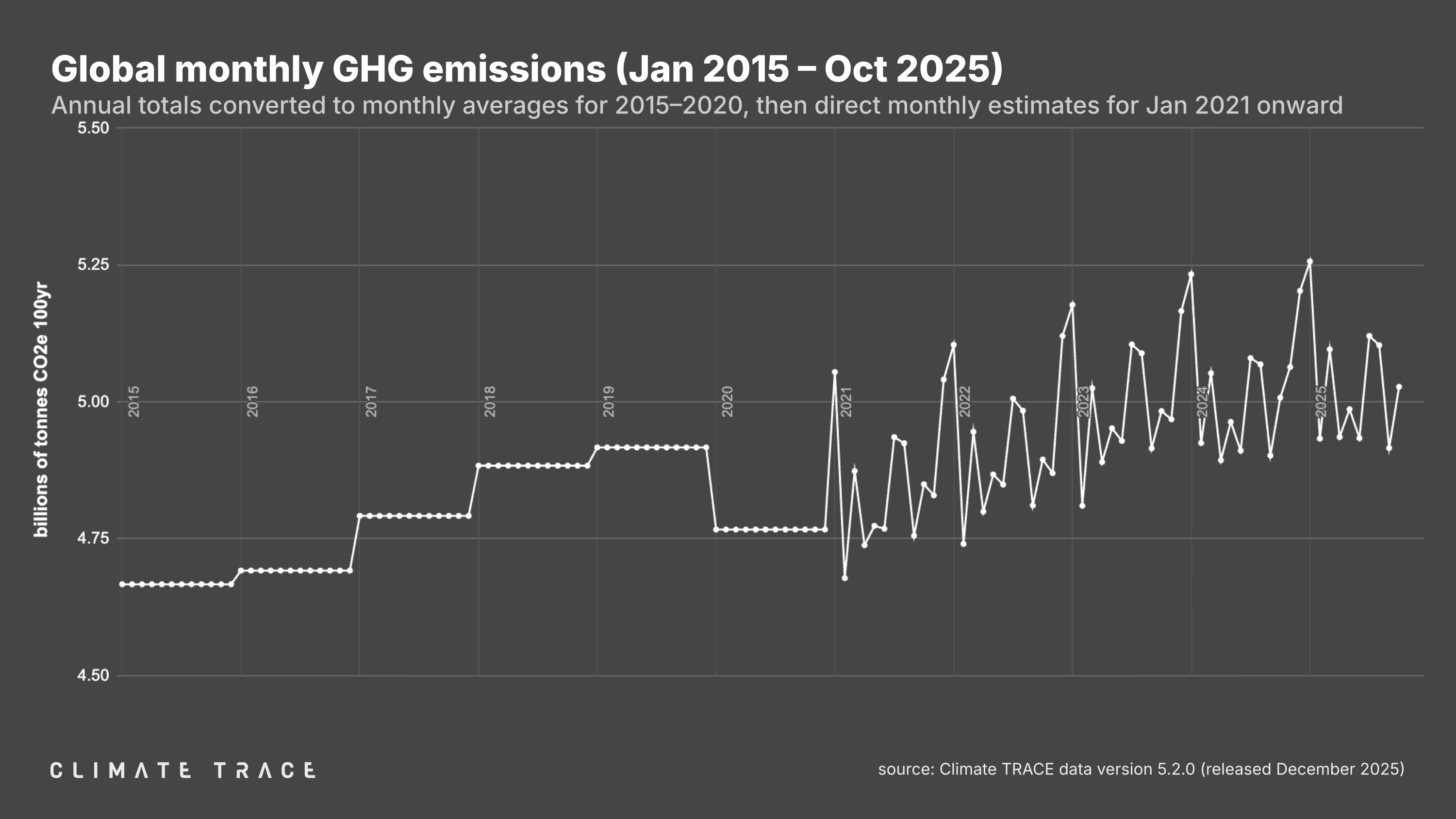

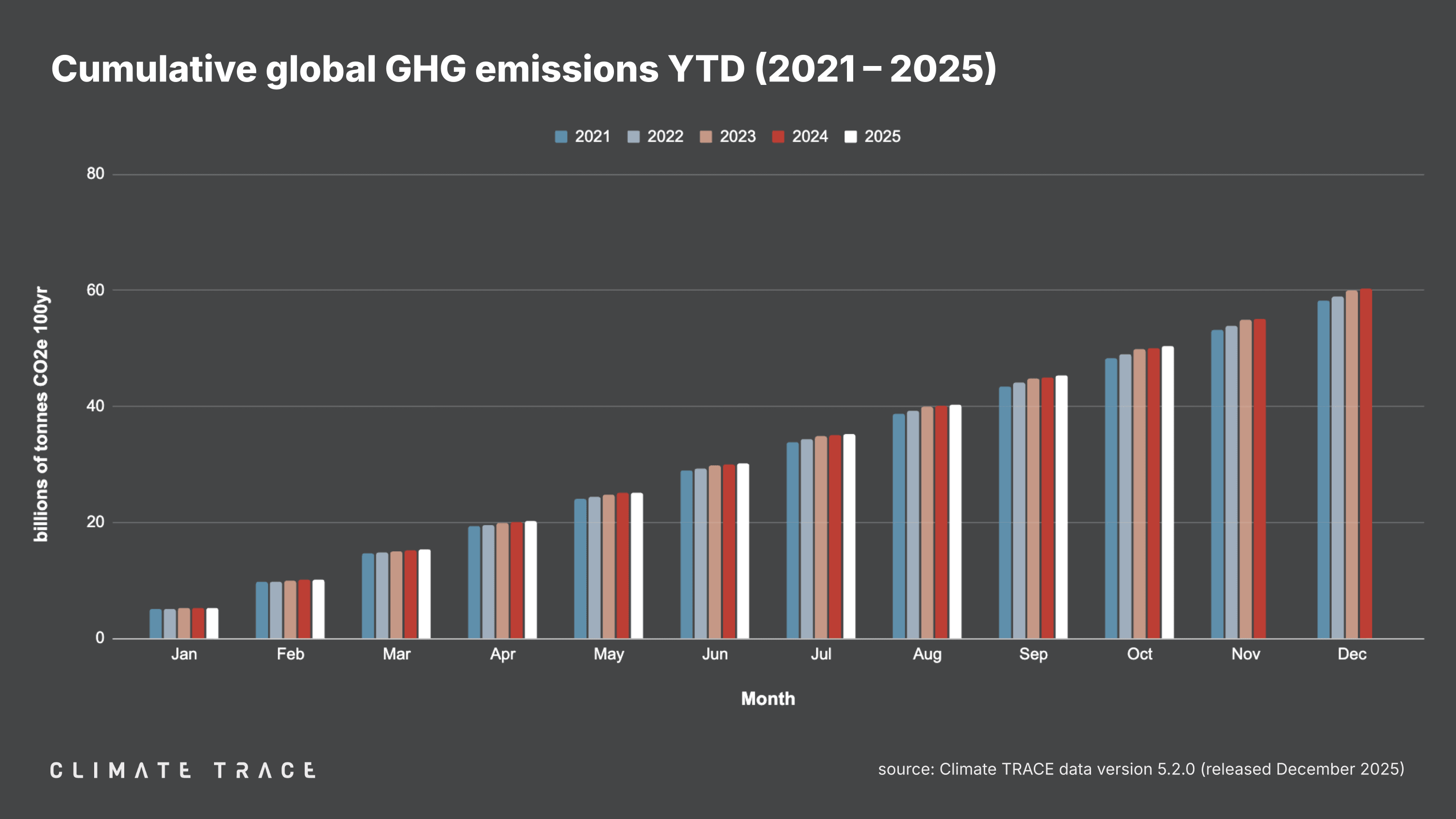

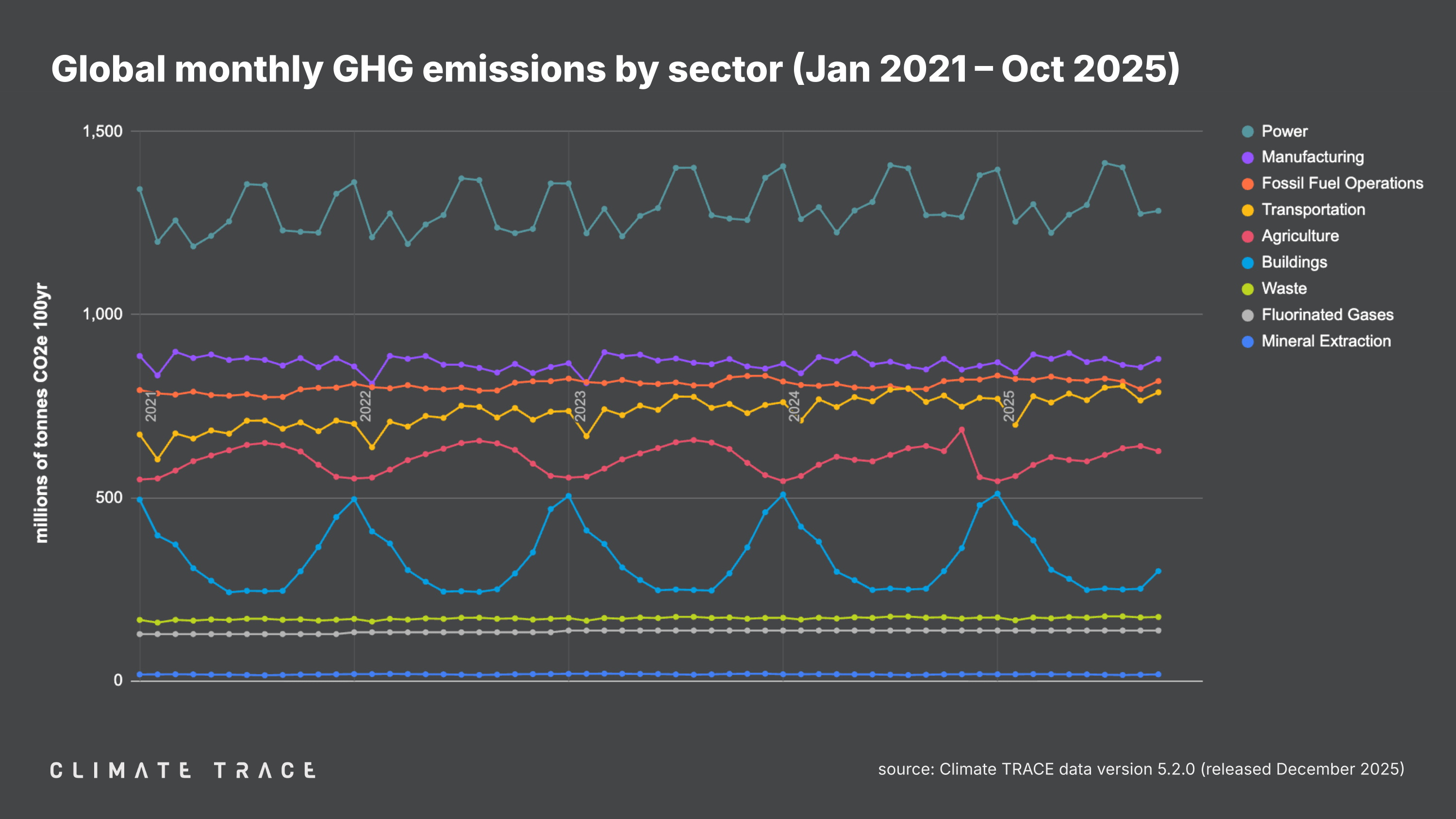

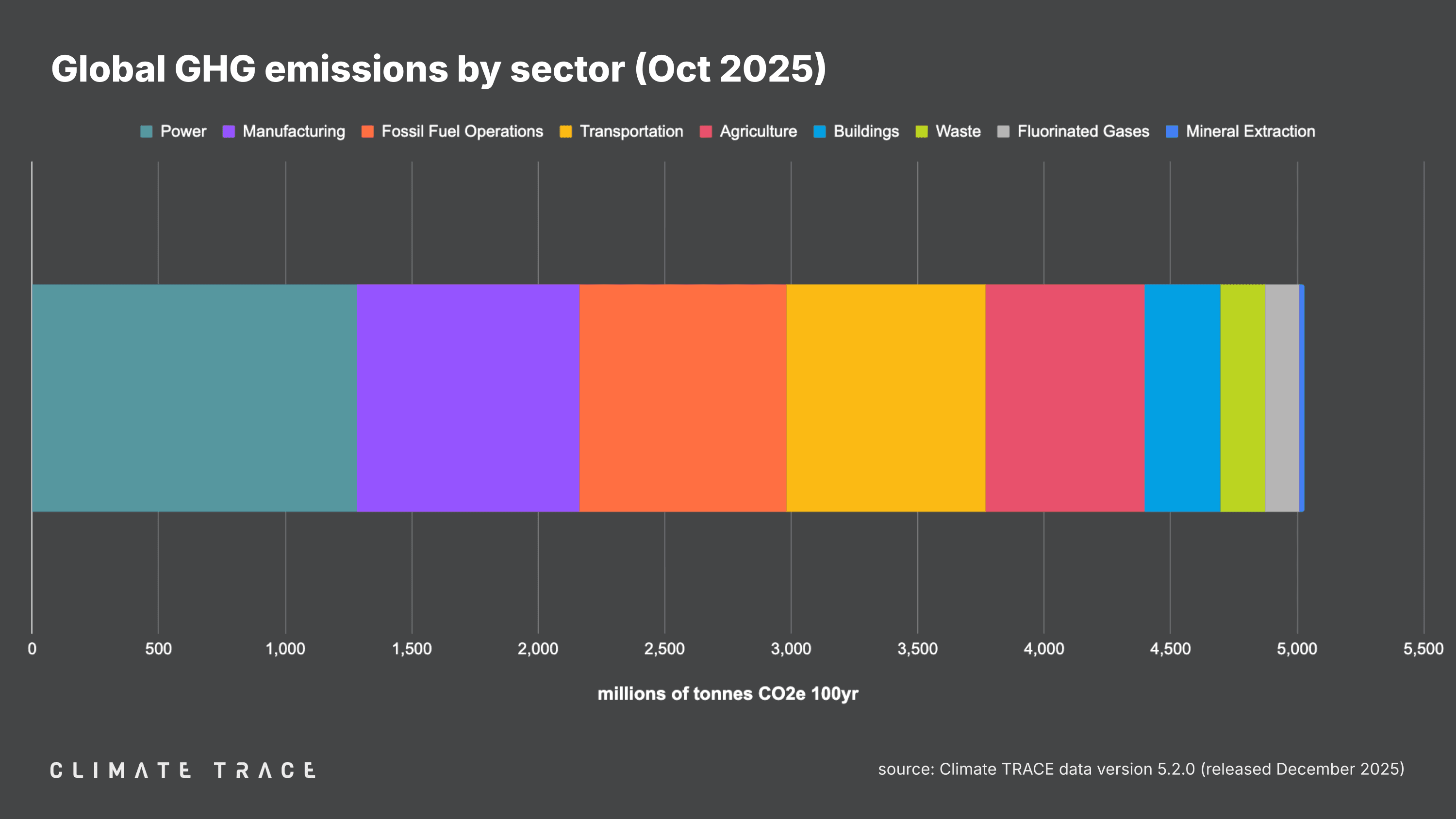

December 18, 2025 – Today, Climate TRACE reported that global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for the month of October 2025 totaled 5.03 billion tonnes CO₂e. This represents an increase of 0.40% vs. October 2024. Total global year-to-date emissions are 50.31 billion tonnes CO₂e. This is 0.55% higher than 2024's year-to-date total. Global methane emissions in October 2025 were 33.83 million tonnes CH₄, an increase of 0.07% vs. October 2024.

Data tables summarizing GHG and primary particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions totals by sector and country, and GHG emissions for the top 100 urban areas for October 2025 are available for download here.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Country: October 2025

Climate TRACE's preliminary estimate of October 2025 emissions in China, the world's top emitting country, is 1.42 billion tonnes CO₂e, an increase of 8.46 million tonnes of CO₂e, or 0.60% vs. October 2024.

Of the other top five emitting countries:

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector: October 2025

Greenhouse gas emissions increased in October 2025 vs. October 2024 in power, transportation, and waste, and did not decrease in any major sectors. Transportation saw the greatest change in emissions year over year, with emissions increasing by 1.13% as compared to October 2024.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by City: October 2025

The urban areas with the highest total GHG emissions in October 2025 were Shanghai, China; Tokyo, Japan; Houston, United States; New York, United States; and Los Angeles, United States.

The urban areas with the greatest increases in absolute emissions in October 2025 as compared to October 2024 were Ramagundam, India; Obra, India; Newcastle, Australia; Toranagallu, India; and Owensboro, United States. Those with the largest absolute emissions declines between this October and last October were Waidhan, India; Korba, India; Anpara, India; Rotterdam [The Hague], Netherlands; and UNNAMED, India.

The urban areas with the greatest increases in emissions as a percentage of their total emissions were Butibori, India; Uruguaiana, Brazil; Shitang, China; Obra, India; and Shostka, Ukraine. Those with the greatest decreases by percentage were Heilbronn, Germany; UNNAMED, India; Santaldih, India; Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Russia; and Alotau, Papua New Guinea.

RELEASE NOTES

Revisions to existing Climate TRACE data are common and expected. They allow us to take the most up-to-date and accurate information into account. As new information becomes available, Climate TRACE will update its emissions totals (potentially including historical estimates) to reflect new data inputs, methodologies, and revisions.

With the addition of October 2025 data, the Climate TRACE database is now updated to version V5.2.0. This release expands asset coverage to include 245 additional power plants (globally) and 2,287 additional cattle operations (all in Japan). It includes non-greenhouse gas emissions for petrochemical steam cracking facilities in Asia Pacific and the Middle East. The waste sector has updated modeling for its landfill emissions: emissions are now modeled natively for each month, where previously, annual estimates were disaggregated into monthly estimates. The release also includes data fixes within transportation and waste sectors.

A detailed description of data updates is available in our changelog here.

To learn more about what is included in our monthly data releases and for frequently asked questions, click here.

All methodologies for Climate TRACE data estimates are available to view and download here.

For any further technical questions about data updates, please contact: coalition@ClimateTRACE.org.

To sign up for monthly updates from Climate TRACE, click here.

Emissions data for November 2025 are scheduled for release on January 29, 2026.

About Climate TRACE

The Climate TRACE coalition was formed by a group of AI specialists, data scientists, researchers, and nongovernmental organizations. Current members include Carbon Yield; Carnegie Mellon University's CREATE Lab; CTrees; Duke University's Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment & Sustainability; Earth Genome; Former Vice President Al Gore; Global Energy Monitor; Global Fishing Watch/emLab; Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab; OceanMind; RMI; TransitionZero; and WattTime. Climate TRACE is also supported by more than 100 other contributing organizations and researchers, including key data and analysis contributors: Arboretica, Michigan State University, Ode Partners, Open Supply Hub, Saint Louis University's Remote Sensing Lab, and University of Malaysia Terengganu. For more information about the coalition and a list of contributors, click here.

Media Contacts

Fae Jencks and Nikki Arnone for Climate TRACE media@climatetrace.org

This analysis and news roundup come from the Canary Media Weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it every Friday.

President Donald Trump’s sweeping freeze on offshore wind construction is starting to hurt his own party’s energy ambitions.

Just days before Christmas, the Trump administration halted work on all five large-scale offshore wind farms under construction in the U.S, citing unspecified national security concerns. The order may have come as a shock to the project developers, who received letters from the Interior Department only after Fox News publicly reported on the move, as Canary Media’s Clare Fieseler reported at the time.

All but one of the targeted developers have since sued the Trump administration. Danish developer Ørsted filed two separate suits over pauses to its nearly complete Revolution Wind — which the Interior already halted for a month last fall — and to Sunrise Wind. In another lawsuit, Equinor warned that the freeze would result in the “likely termination” of its Empire Wind project off New York, which also suffered a monthlong stop-work order last spring. And Dominion Energy is asking a judge to let construction resume on the utility’s Virginia project, once considered safe because it had the backing of the state’s outgoing Republican governor.

The halts are also sparking backlash on Capitol Hill that could derail some of the White House’s other energy plans. In the weeks leading up to the holidays, Congress had taken up what seemed like the millionth round of negotiations to reform energy-project permitting. Reforms are essential to Republicans’ goal of speeding fossil-fuel construction, and this time around, they’d actually made progress with the House’s passage of the SPEED Act, which had support from a handful of Democrats.

That bill requires 60 votes to clear the Senate, but with Republicans holding just 53 seats, it would need significant Democratic support. That won’t happen while the Interior’s stop-work order remains in place, two high-ranking Senate Democrats say.

“The illegal attacks on fully permitted renewable energy projects must be reversed if there is to be any chance that permitting talks resume,” Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) and Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) said in a late December statement calling out the offshore wind halts. “There is no path to permitting reform if this administration refuses to follow the law.”

Congress reconvened this week, but Whitehouse affirmed that permitting talks won’t go anywhere until offshore wind construction is free to proceed.

Venezuela is dominating the energy discussion

While the Trump administration used allegations of narcoterrorism to justify its invasion of Venezuela and seizure of leader Nicolás Maduro, pretty much every conversation since has revolved around the country’s oil resources. In his first news conference after Maduro’s capture, President Donald Trump said the U.S. would “run” Venezuela and control its oil production, and he has been pressuring American oil companies to reinvest in the South American nation.

But it’s not just oil that the White House is eyeing. An administration official told Latitude Media that Trump and the private sector may also target Venezuela’s critical mineral resources, though experts warn that little reliable data exists on those deposits and that the country’s mining sectors are in disarray.

More delayed coal-plant retirements

The U.S Department of Energy issued a wave of orders in the waning days of 2025 to keep coal power plants running past their retirement dates. The first targeted a plant in Centralia, Washington, which its owner had been planning to close since 2011. Next up came orders to keep two Indiana coal plants open until at least late March. And just before year’s end came another, this one targeting Unit 1 at Colorado’s Craig power plant.

Both the Craig facility and one of the units in Indiana have been out of commission due to mechanical failures since earlier in 2025, meaning their owners will now have to shoulder potentially huge repair costs to comply with the federal mandate, Canary Media’s Jeff St. John reports.

And the U.S. EPA may soon throw another lifeline to coal power. The agency plans to let 11 plants dump toxic coal ash into unlined pits years after current federal rules allow, Canary Media’s Kari Lydersen reports. Without the extension, those plants would likely shutter.

A just transition? As the European Union shifts off coal, advocates and leaders are working to ensure Poland’s powerhouse mining region isn’t left behind. (Canary Media)

It’s electrifying: The rising cost of natural gas and growing popularity of heat pumps and induction cooking indicate a bright future ahead for building electrification in the U.S. (Canary Media)

State of the emergency: In the year since Trump declared a national emergency on energy, experts say an actual electricity-supply crisis has emerged, and the White House is discouraging renewable energy development that could help solve it. (Canary Media)

A new EV champion: Tesla’s sales fell year-over-year in 2025, finishing at 1.64 million deliveries, putting the company’s sales totals behind emerging Chinese company BYD, which sold 2.26 million EVs. (AFP)

Back from the dead: Nearly obsolete fossil-fuel-fired peaker plants are being forced back into service thanks to rising electricity demand from AI data centers. (Reuters)

Solar’s bigger in Texas: Data shows that solar arrays provided more power to Texas’ standalone grid in 2025 than did coal-fired power plants, marking the first time that has happened. (Houston Chronicle)

Out in the fertile yet water-constrained farmlands of California’s western Central Valley, a massive solar, battery, and power grid project that could provide a quarter of the state’s clean energy needs by 2035 has taken a critical step forward.

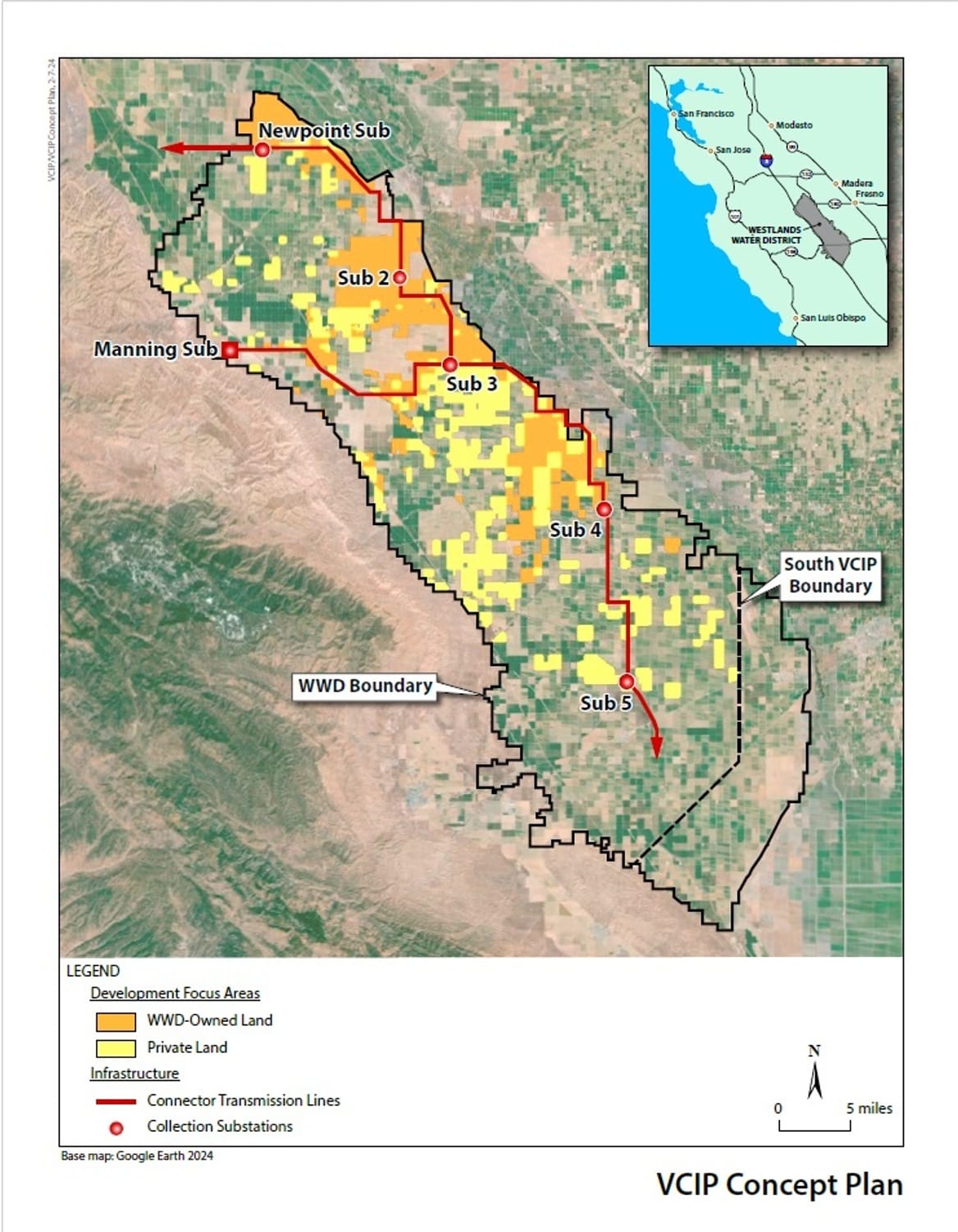

In December, the board of directors of the Westlands Water District, the agency that manages water delivery to more than 600,000 acres in California’s agricultural heartland, approved the Valley Clean Infrastructure Plan. VCIP calls for building up to 21 gigawatts of solar energy and an equivalent amount of battery storage across up to 136,000 acres, along with a series of high-voltage transmission lines to connect the electricity generated to the state’s grid.

That would be the largest solar and battery project in the country, and it will take up to a decade to be completed. But Patrick Mealoy, a partner and chief operating officer of Golden State Clean Energy, the company developing the master plan in partnership with the district, said it’s expected to move quickly, with the first construction work potentially happening within the next two years.

Golden State Clean Energy will carry out only a small part of the project, Mealoy said. It will mostly seek third-party solar and battery developers, with individual installations ranging in size from 100 to 1,150 megawatts.

Mealoy, a 30-year solar veteran, codeveloped Westlands Solar Park, the first major solar farm in the district. When fully completed, that project will be one of the largest in the Central Valley and produce 2.7 gigawatts — a fraction of VCIP’s scope.

The VCIP is designed to manage the multiple challenges that can stymie piecemeal solar and battery projects, such as winning environmental approvals, securing buy-in from landowners and communities, and interconnecting to the state’s congested transmission grid, Mealoy said.

“We’re doing the transmission studies, the environmental impact studies, and outreach to communities, all at the same time, to make sure there are no showstoppers.”

The VCIP is as much about preserving the region’s agriculture industry as it is about generating clean electrons, said Allison Febbo, the district’s general manager. That’s because the plan will allow the district’s more than 700 growers to redirect increasingly limited water supplies from land slated for clean energy development to land that remains under cultivation.

“The real benefit to us is that it gives our growers another crop to grow, which is the sun,” she said. “Our growers have this issue: ‘I have 100 acres of land but only enough water to irrigate 50 of those acres. What do I do with the remainder of those acres?’”

For decades, California’s Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta has delivered water via the Central Valley Project’s system to irrigate the Westland Water District, the largest water district in the country. But in recent years, restrictions brought on by environmental and endangered species regulations for the delta have forced Westlands to fallow an increasing amount of farmland, expanding to more than one-third of its total acreage. And under the state’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, farmers will soon face stringent restrictions on how much water they can pump from the region’s long-stressed aquifers.

As more and more land has been left uncultivated, farm employment and property tax revenues have declined in the region. “The schools can’t be supported, the businesses can’t be supported,” Febbo said. “This is a way to maintain economic viability and support our communities.”

Mealoy said the VCIP could revitalize the region’s economy. “The cost of building solar is well north of $1 million per megawatt, probably closer to $1.5 million,” he said. Spread across 21 gigawatts of planned development, “that’s billions and billions of dollars that could be built on fallowed ag land, creating jobs and creating an enormous tax base for Fresno County,” which encompasses the land being set aside for development.

The economic benefits would extend beyond the region. An analysis commissioned by Golden State Clean Energy last year found that the clean energy and transmission congestion relief the plan would deliver could yield annual electricity cost savings of about $850 million and reduce the state’s power-sector carbon emissions by 15% through 2050.

The plan will also help reduce the grid congestion that’s created yearslong interconnection delays for large-scale solar and battery projects throughout the state, Mealoy said. In 2024, state lawmakers passed Assembly Bill 2661, a law that allows the Westlands Water District to develop its own transmission grid to get solar to market.

The project’s transmission infrastructure will be constructed under a project labor agreement using 100% union labor. That has won it the backing of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 1245, which represents workers at Pacific Gas & Electric, the state’s largest utility.

Westland Water District’s approval of VCIP’s programmatic environmental impact report last month will allow the next big phases of the project to move ahead, Febbo said.

“With this master-planned approach, we’ll have one set of guidance, one set of rules. We’ll be able to handle how land is managed, how pests are managed, dust control — all of those things can be dealt with on a large scale.”

The project should deliver other benefits to the surrounding communities as well. Westlands Water District is bound by state law to develop community benefits agreements to provide funding for job training, environmental remediation, economic development, and other community needs for the roughly 15,000 people living nearby.

Those residents don’t want energy extraction to come at their expense, said José Antonio Ramírez, city manager of the town of Livingston and acting director of Rural Communities Rising, a newly formed collaborative of unincorporated communities. An earlier endeavor, the Darden Clean Energy Project, to be built on land to be purchased from Westlands Water District, has been criticized for having an inadequate community benefits plan.

Febbo said the district is “committed to a community benefit program, so tax revenues and other revenues will be spent on the communities that need it,” but that this work has only just begun.

Ramírez said his group is pressing for the unincorporated communities it represents to have a say in how that plan is shaped. “A lot of people out here are just making ends meet on a day-by-day scenario,” he said. “I don’t think our communities know the opportunities before them — and that these opportunities can go south if they don’t speak for themselves.”

A federal judge has ruled that Ørsted can resume the construction of its nearly complete, 704-megawatt Revolution Wind project off the coast of Rhode Island.

The decision on Monday comes after the Trump administration issued stop-work orders to all five of the offshore wind projects under development in the U.S. in late December, the culmination of President Donald Trump’s yearlong war against the renewable energy source.

Revolution Wind, a $6.2 billion project that is nearly 90% complete, was hit with an earlier federal stop-work order in August from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, a division of the Interior Department. A federal judge ruled in favor of Ørsted in September, allowing the project to move forward until December’s order, which cited unspecified issues of “national security.”

On Monday, the Danish developer said it will “resume construction work as soon as possible” while its complaint against the Trump administration is heard by the courts.

Judge Royce Lamberth of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, who issued the injunction, said from the bench on Monday that the bureau’s August suspension order was “the height of arbitrary and capricious” and that the December order’s vague claims of national security risks did “not constitute a sufficient explanation for the bureau’s decision to entirely stop work on the Revolution Wind project.” He noted that the government’s argument for halting construction was “unreasonable and seemingly unjustified.”

Each offshore wind project has been repeatedly vetted by the Department of Defense since being proposed, and developers said they were blindsided by the Trump administration’s latest security concerns.

Ørsted and two other offshore-wind developers, Equinor and Dominion Energy Virginia, all sued to vacate the Trump administration’s 90-day construction freeze from December. Ørsted’s court hearing was the first, and judges are set to consider the fate of the other in-progress offshore wind projects this week.

On Wednesday, a court could decide on Equinor’s 810-MW Empire Wind project, which also previously received and defeated a stop-work order. A hearing for Dominion Energy’s massive 2.6-gigawatt Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project is scheduled for Friday. In addition to energy developers, the states of Connecticut, New York, and Rhode Island have all sued to get the projects going again.

The stakes are high: In total, the five offshore wind farms affected by the Trump administration’s December order would bring nearly 6 GW of capacity to the grid, or enough to power roughly 2.5 million homes across the East Coast.

The U.S. can’t afford to lose any of these projects. Energy demand is climbing across the nation, causing household utility bills to soar. More power plants are needed to keep bills from rising even further — especially in regions swamped with power-hungry data centers, like Virginia.

In addition, grid operators have been banking on the arrival of these large-scale offshore wind projects, several of which are more than halfway complete. In August, ISO-New England issued an unprecedented warning that the Trump administration’s first pause on Revolution Wind created “unpredictable risks” that could “undermine the power grid’s reliability and the region’s economy now and in the future.”

At least one project could be abandoned imminently. Equinor, which already lost nearly $1 billion because of the first stop-work order on Empire Wind, says the beleaguered project faces “likely termination” if it can’t continue work by this Friday.

Meanwhile, industry groups applauded Monday’s decision.

Kat Burnham, the New England policy lead for Advanced Energy United, said the D.C. court “rightly saw through a politically motivated stop-work order that would have caused real harm: driving up costs, delaying power for Rhode Island and Connecticut, and putting good-paying jobs at risk.” In a statement, she said the decision is “good news for workers, ratepayers, and anyone who recognizes the need for a fair energy market.”

The latest skirmish over offshore wind comes after a year of assault from the Trump administration. Trump has gummed up the build-out of onshore wind and solar power, too — but no energy source has been targeted like offshore wind.

The impact of Trump’s war on the sector is profound.

When he was reelected in 2024, BloombergNEF expected 39 GW of offshore wind capacity to come online in America by 2035. The research group hedged that number to 21.5 GW if Trump managed to repeal wind tax credits during his term. He did. As of October, BNEF expected just 6 GW to get online by 2035 — a number that will be even lower if any of the in-progress projects buckle under the weight of the latest order.

Sergio Mendez was tired of earning a living by working security in nightclubs. So the 22-year-old resident of Chicago’s Southwest Side decided to make a big change, enrolling in a 10-week program that promised to teach him the fundamental skills needed to pursue a career in the solar industry.

“I was just dealing with a lot of drunk people. I wanted to get out of it,” Mendez said of his former job. Now he envisions a future as a solar salesperson or installer. In late December, he graduated alongside six other young adults enrolled in the course, run by Elevate, a national clean-energy nonprofit based in Chicago.

The cohort is stepping into an industry that experts say is going strong in Illinois, even as the Trump administration cancels clean-energy tax credits, claws back funding for pollution-reducing projects, and enacts other policies that make it harder to build renewable energy.

Illinois has emerged as a solar leader in recent years, thanks in large part to its robust incentives and its mandates that utilities get an increasing amount of electricity from renewables. In 2024, the state ranked fourth nationwide in terms of new solar capacity, with over 2,800 megawatts installed, and it added another 815 megawatts in the first three quarters of 2025, according to a December report by consultancy Wood Mackenzie and the Solar Energy Industries Association.

The industry’s momentum translates to lots of employment opportunities: The Solar Energy Industries Association counted almost 6,000 solar jobs in Illinois in 2025, and it projects that the state will add close to another 15,000 megawatts of solar over the next five years.

“With energy demand growing — some would say, out of control — solar is the fastest [generation source] to deploy,” said J.D. Smith, a spokesperson for the Wisconsin-based solar installer Arch Electric. “From a technical standpoint, if you’re trying to power the grid, [solar] is such a good decision. You can get it cheap and fast, and it’s repeatable.”

Companies expanding to meet that demand are eager to snap up graduates of workforce development programs.

In the past year, Arch — one of the employers at a December job fair for Mendez and his peers — has hired 14 graduates of training programs run by Elevate and other Chicago-area nonprofits. Seven of those individuals are already in apprenticeships to become certified electricians.

“If you know at least 50% of the people you hire from these organizations will want to be an apprentice and invest in their future with your organization, that makes it a business no-brainer,” Smith said.

Solar companies also rely on training programs to produce qualified candidates from what the state has defined as “equity” communities, he explained. Under Illinois’ 2021 clean-energy law, firms can access incentives for hiring individuals from these areas, which face disproportionate amounts of pollution and have historically been excluded from economic opportunities.

“There is an enormous demand for these programs,” Smith said. “We will take everyone we can get who is willing to invest their time and learn.”

The course that Mendez graduated from marks Elevate’s first solar training aimed specifically at adults between the ages of 18 and 24.

Many of the participants, including Mendez, are alumni of the Academy for Global Citizenship, a K–8 charter school on Chicago’s Southwest Side that hosted the course in two geodesic domes built specifically for the program. The school’s campus boasts both ground-mounted and rooftop solar panels, as well as a geothermal heating and cooling system.

“When you’re around it since you’re young, it’s just normal,” Mendez said of solar.

Solar training in session on Dec. 4, 2025, inside one of the geodesic domes at Chicago’s Academy for Global Citizenship (Kari Lydersen/Canary Media)

Over the course of Elevate’s training, students learned about everything from the basics of electricity to solar system installation. They got hands-on practice with panels and wiring and took a field trip to see one of Illinois’ many community solar arrays. And they prepared for the North American Board of Certified Energy Practitioners exam; a certification like the one issued by NABCEP is required to install solar on buildings in most states, including Illinois.

“We see how to set up a solar panel system, how all the parts work, how we make sure not to blow anyone up,” said student Josh Paz, age 23, another alumnus of the charter school. Before enrolling in Elevate’s training, he had worked in retail stores, in warehouses, and as a landscaper.

“I’ve always liked to work with my hands, so it’s pretty fun,” he said of solar. “And we’re building a cleaner future. America’s a little behind the rest of the world, but it’s good to see solar growing exponentially.”

Other graduates of the Elevate program are similarly bullish about building a career in clean energy — and using it to address societal injustices in Chicago and beyond.

“You see the discrimination, the amount of residential areas near power plants, all Black and brown people,” said 21-year-old Matthias Hunter. “The race for renewable energy in America is going to be a challenge, especially with this administration. But there’s light at the end of the tunnel. This is the future. It’s not optional.”