There’s no sugarcoating it: A new North Carolina law unraveling utility Duke Energy’s climate goals is a massive setback for the state’s clean energy transition, and it’s being exacerbated by the Trump administration’s full-scale assault on wind and solar power across the country.

Yet many observers believe that in the short term the renewable energy sector will bend but not break — buoyed by the realities of rising electricity demand and the increasingly bleak economics of fossil fuels.

The Republican-led legislature passed Senate Bill 266 last month, overriding the veto of Gov. Josh Stein, a Democrat. The legislation erases a 2030 deadline by which Duke must cut its carbon emissions by 70% compared to 2005 levels, though it retains a mandate for the utility to decarbonize by midcentury.

Those deadlines were set into state law in resounding bipartisan fashion only four years ago, with just over two dozen “no” votes in the GOP-controlled House and Senate combined.

But it was a different era politically. Democrat Joe Biden had just won the presidency, spurred in part by voters animated by the climate crisis. Then-Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, had made promoting the clean energy economy a signature of his administration, and his party held enough seats in both chambers to sustain his veto.

Elected in 2024, Stein has made no secret of his support for clean energy, but his focus to date has been recovery after Hurricane Helene, which struck the state nearly a year ago. Republicans in the General Assembly are only one vote shy of a supermajority. President Donald Trump’s stunning attack on wind, solar, and climate science has given license to like-minded allies in his party and in powerful state industrial groups to follow his lead.

The utility landscape has also shifted dramatically. In 2021, Duke, ever-influential with lawmakers, was willing to compromise on a wide-ranging energy bill to secure approval for a long-sought multiyear ratemaking scheme. Before a cleantech manufacturing resurgence and the explosion of AI, the company also faced relatively flat electric demand. State utility regulators, all but one appointed by Cooper, appeared inclined toward climate action, even if they sometimes frustrated advocates.

Today, Republican-appointed members — including one with an apparent axe to grind against solar — comprise the majority on the Utilities Commission. After the passage of SB 266, the panel wasted no time in ordering Duke to stop near-term planning for cutting its carbon emissions by 70%.

Duke still must zero out its climate-warming pollution by 2050, and its latest plan for doing so is due Oct. 1. But if predictions from Public Staff, the state-sanctioned customer advocate, are any indication, removing the near-term goal could mean seismic changes to the company’s forecast for the next decade.

With the blessing of regulators, the company was already on pace to miss the interim target by five years. Without any midway goal, Duke could build about 12 fewer gigawatts of new power capacity by 2035 and lean harder on aging fossil-fuel plants and purchased power instead. The forgone generation includes 4.4 gigawatts of solar, 2.8 gigawatts of battery storage, and 4.5 gigawatts of wind, according to Public Staff.

Advocates are working hard to make sure those predictions don’t come true.

One dynamic that may help is the urgency of rising electricity demand. According to June figures from Duke, new economic development projects in the form of data centers and other large customers could require roughly 6 new gigawatts of capacity by 2030.

Yet wait times for new natural gas turbines are as long as seven years, according to S&P Global. And Duke plans to be a so-called second mover on small modular nuclear reactors — meaning it doesn’t foresee becoming the first U.S. utility to put the nascent resource into service. A new reactor won’t come online for at least 10 years, per the company.

Even if the most extreme predictions about new economic development don’t pan out, solar and battery storage, and even onshore wind, are all poised to fill a need left by these delays, advocates say.

“It’s a matter of meeting a deficit — a potential deficit — in energy demand,” said Karly Brownfield, a senior program manager with Southeastern Wind Coalition, a nonprofit that advocates for the industry. With similar development timelines as gas and a well-established and tested permitting process in the state, she said, “I think onshore wind is definitely going to continue to move to the front.”

Another factor favoring renewables: cost. While the tax and spending bill signed by Trump this summer indubitably scrambles the calculus on wind and solar by phasing out tax incentives more quickly than before and making them harder for developers to access, these resources are still cheaper than new fossil-fueled plants — even without subsidies. The cost of battery storage, meanwhile, continues to decline.

At the same time, the specter of rising natural gas prices should loom large, says Josh Brooks, chief of policy strategy and innovation with the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association. “The passage of SB 266 puts into sharp focus retail ratepayer exposure to fuel-price volatility,” he said. “The best and quickest opportunity to address that risk is through distributed renewables — especially solar paired with storage.”

Brownfield is also not giving up on offshore wind, despite the Trump administration’s aggressive antipathy for ocean-based turbines and Duke’s recent decision not to solicit any offshore projects in the near term. The three developers who hold leases off North Carolina’s coast have spent relatively little on their projects so far, Brownfield said. They can bide their time until the politics and the economics become more favorable.

“They’re early enough in the process that they feel like they can mitigate that risk over the next couple of years,” Brownfield said. “The conversation about offshore wind is not going to go away.”

Advocates also point to the colossal economic development impact of renewables in the state — from the farmers who increase their profit margins by leasing land for turbines or solar panels to the county commissioners looking to fund public schools. An analysis released just before lawmakers passed SB 266 showed the law could cut investment in power plant construction by more than $47.2 billion between 2030 and 2035, and reduce tax revenue by more than $1.4 billion — mostly because of forgone renewable energy development.

In hurricane-prone North Carolina, resiliency concerns loom large, too, said Brooks, who noted the success of solar microgrids and other climatetech in the wake of Helene’s devastation. “There’s no doubt about it that that was the quickest way to respond to Helene,” he said. “As incidents like that increase, we’re only going to see more need for the utility to think about decentralized assets.”

Even without the 2030 carbon goal, clean energy advocates will have several chances over the next year to advance these arguments before the Utilities Commission.

An analysis of Duke’s large load growth projections is ongoing, and an expert witness hearing is scheduled for October. The company’s latest draft plan for phasing out climate-warming emissions comes this fall and must be finalized by the end of 2026. What’s more, Duke is proposing to merge its two separate utilities in North Carolina, and could soon proffer another three-year rate increase to begin in 2027.

“There’s going to be tens of billions of dollars of investment decisions made at the regulatory level in the next year,” said Will Scott, Southeast climate and clean energy director for Environmental Defense Fund.

Regulators have also directed the company to test gas-fired plants that can be fueled with hydrogen. If that experiment ultimately proves unworkable, it could force Duke to abandon its apparent plan to convert its fossil-fueled plants to hydrogen at the last minute to comply with the midcentury carbon deadline.

“Given how big a piece hydrogen was in their 2050 plan, in terms of reducing emissions from the new proposed gas units, that’s going to be good to keep an eye on,” Scott said.

Still, the immediate future of renewables is likely to depend most on Duke itself, whose sway with regulators appears steadfast as ever. And the company’s shareholders, who per one Wall Street firm secured a “more predictable earnings trajectory” from the passage of SB 266, could pull away from wind and solar and toward more robust investments in fossil fuels.

What’s more, the current political climate, as set by the White House, could embolden anti-clean-energy lawmakers to push to eliminate Duke’s carbon goals entirely before possible Republican losses in next year’s midterms.

Advocates are clear-eyed about that risk. But they also point to electric bills that are already rising and predicted to climb even more under SB 266, especially for households. That could create the impetus for bipartisan legislation to course correct.

“I can easily foresee a world where we do not have to engage much to get parts of this bill overturned in a future session once the economic realities of it hit the ratepayers,” Brooks said.

Nippon Steel, the parent company of U.S. Steel, is moving forward with its plans to renovate a giant coal-fueled furnace in Gary, Indiana.

The Japan-based steel manufacturer, which acquired U.S. Steel in June, will begin “relining” its largest blast furnace at the Gary Works steel mill in 2026, U.S. Steel CEO David Burritt said this week at an industry conference in Atlanta, details first reported by the Japanese newspaper Nikkei.

Such an investment can extend a furnace’s operating life by up to 20 years — prolonging the company’s reliance on coal-based steelmaking, and potentially delaying America’s broader transition to low-carbon manufacturing methods.

Nippon Steel has committed to spending around $300 million to revamp Blast Furnace No. 14, the largest of four blast furnaces still operating at the sprawling Gary Works complex on Lake Michigan. The Japanese steelmaker said it will spend a total of $3.1 billion across Gary Works as part of a $11 billion capital investment in U.S. Steel’s footprints through 2028.

“Gary Works supports a large number of jobs and demand in the Midwest, and we are moving forward with numerous investment plans to support the industry,” Burritt said at the conference, adding that U.S. Steel and Nippon Steel expect to announce more specific details about their plans soon. (A spokesperson for U.S. Steel confirmed Burritt’s remarks in an email.)

Blast furnaces make the iron that’s turned into high-strength steel, an essential material found in everything from cars, boats, and planes to buildings, bridges, and roads.

The scorching-hot furnaces combine iron ore with purified coal, or “coke,” and limestone to produce liquid iron, which is then moved into a separate furnace to become steel. Only seven of these integrated iron and steel facilities are currently operating in the United States, accounting for about a quarter of total U.S. steel production. But the steel mills are responsible for around 75% of the industry’s greenhouse gas emissions. They’re also among the biggest sources of toxic air pollution in the communities where they operate.

A recent report by the Environmental Integrity Project found the Gary Works complex is a major source of health-harming pollutants like chromium, which can cause breathing problems and increase the risk of lung cancer.

America’s blast furnaces — among the oldest in the world — use specialized bricks that degrade over time. When that happens, companies can decide to undertake a costly and lengthy maintenance process to replace the bricks and prop up aging plants. Or they can put that money toward building cleaner facilities that make use of “direct reduced iron” technology that doesn’t require coal.

Climate advocates and community groups in Gary, Indiana, are urging Nippon Steel to take the second route.

“Today, the company is at a crossroads,” Toko Tomita, campaigns director at the advocacy group SteelWatch, said in a statement. “If this relining decision goes ahead, it would be a slap in the face for communities, and a coffin-nail for Nippon Steel’s reputation on climate.”

Tomita said that relining the Gary Works furnace is “an extremely short-sighted move” that will leave Nippon Steel with outdated facilities at a time when automakers and other major steel buyers are increasingly signaling their demand for products made using lower-emission methods.

At the moment, however, America’s steelmakers seem committed to keeping their coal-based mills up and running.

Along with its four Gary Works blast furnaces, U.S. Steel operates two blast furnaces at its Edgar Thomson plant in the Mon Valley Works in southwestern Pennsylvania — the same complex that suffered a deadly explosion on Aug. 11 at a coke-producing plant. Nippon Steel has announced plans to schedule all six blast furnaces for relining or major repairs by 2030 in order to “extend their useful lives for many years to come.”

Cleveland-Cliffs, the only other U.S. steelmaker that uses coal-fueled facilities, operates blast furnaces across its steel mills in Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan. The Ohio-based firm has said it plans to reline a furnace at its Burns Harbor steel plant in Indiana in 2027.

On an earnings call last month, Cleveland-Cliffs CEO Lourenco Goncalves confirmed that, in addition to the relining, the company is no longer pursuing a federally supported project to build a new green steel facility in Middletown, Ohio. Cleveland-Cliffs is instead working with the Trump administration to “preserve and enhance” its Middletown steel mill using fossil fuels.

Canary Media’s “Electrified Life” column shares real-world tales, tips, and insights to demystify what individuals can do to shift their homes and lives to clean electric power.

Heard of Earth Day? Get ready for Sun Day.

On Sept. 21, a Sunday of course, thousands of people will gather across the U.S. to spread the message that the clean energy revolution is here. By harnessing the sun — whose thermal energy also gives rise to wind — instead of burning fossil fuels, we can all enjoy cleaner air, lower utility bills, and a host of other benefits.

The day of action is the brainchild of climate journalist and activist Bill McKibben and is being spearheaded by nonprofit communications lab Fossil Free Media. They and a coalition of dozens of advocacy groups are bringing people together on Sun Day to celebrate the progress humanity has made in advancing and adopting renewable energy — and to push for a faster transition away from fossil fuels.

Helping Americans understand all that clean energy has to offer is more urgent than ever, as the Trump administration continues to target renewables, rapidly phasing out tax credits for solar and wind, halting offshore wind development, and maligning battery projects.

Meanwhile solar and wind power are booming globally. And even in the U.S., more than 90% of new power capacity installed last year came from solar, wind, and batteries. Everywhere, the cost of building renewable power is plummeting, making solar and wind the cheapest sources of new electricity.

“We still think of photovoltaic panels and wind turbines as ‘alternative energy,’ as if they were the Whole Foods of power, nice but pricey. In fact — and more so with each passing month — they are the Costco of energy, inexpensive and available in bulk,” writes McKibben in his new book “Here Comes the Sun: A Last Chance for the Climate and a Fresh Chance for Civilization,” which shines a light on the growth of renewables.

“The general public just isn’t aware of how far clean energy has come,” said Jamie Henn, a longtime climate activist and now head of Fossil Free Media.

Individuals and groups have planned more than 150 community events around the country for Sun Day so far. In New York City, organizers are hosting a festival with informational booths, performances, and face-painting. Around Clemson, South Carolina, residents with homes powered by rooftop solar are throwing open their doors to public tours. In Moscow, Idaho, people will be able to test-drive their neighbors’ zero-emissions cars at an electric-vehicle fair.

“It’s going to be a beautiful day,” said Antonique Smith, a Grammy-nominated singer and actress who cofounded the nonprofit Climate Revival and has assumed the role of Sun Day ambassador.

Inspired by Martin Luther King Jr.’s organizing in churches for the Civil Rights Movement, Smith visits houses of worship to explain that there’s an alternative to the fossil fuel plants that spew cancer-causing pollution disproportionately in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

“Clean energy and solar are so important, especially to communities of color and poor communities,” Smith told Canary Media. “How wonderful is it that we have this solution? … It’s not a luxury anymore.”

At climate events, Smith often sings a slowed-down version of The Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” to honor the power of activism and clean energy. Her rendition is also the anthem for the upcoming day of action, and she’ll be performing the song at Sun Day extravaganzas in Brooklyn and Times Square, she said.

Sun Day will also give people a chance to reflect on the risks of a rapidly warming world, according to the Rev. Fletcher Harper, executive director of GreenFaith, a global interfaith environmental coalition. GreenFaith is working with more than 30 partner groups, representing a couple hundred congregations, that are hosting Sun Day gatherings, including a climate-justice pilgrimage in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

“When you look at the impacts of climate change — dangerous levels of heat, drought that forces small farmers around the world off of land that sustained their families for generations, fires that destroy people’s homes, and floods from severe storms — it’s the destruction of the environment that creates enormous human suffering,” Harper said. “It’s just wrong. … And the crime is that it’s preventable.”

The fossil fuel industry, having peddled its products while knowing the existential threat they pose, is a candidate for “one of Dante’s inner circles,” he noted wryly.

Sun Day’s organizers aim to spark a widespread popular movement whose influence is felt long after the day of action.

“People power is just this incredible way to unlock progress more quickly,” Henn said. “And that’s what we need to meet the kind of climate targets that we have in place.”

With all of its economic and societal advantages, clean energy might be inevitable, but “we can’t let this take 40 years,” he noted. “We need it to happen over the next five to 10 years, [which] will require a real mobilization.”

Solar and wind projects are increasingly hitting resistance at the local level.

“We’re just getting completely outplayed,” Henn said. The fossil fuel industry has “invested in front groups [and] field campaigns” to spread misinformation through Facebook and organize people against clean energy, he noted.

Sun Day will bring together people who can call on local leaders, regulators, and representatives to deliver clean energy now. Indeed, Fossil Free Media is already helping build those local grassroots networks, said Deirdre Shelly, who’s leading organizing efforts for the big day.

Want to participate but not sure where to jump in? Start by checking out Sun Day’s map to see if an event is already scheduled in your area. If you want to plan your own shindig, organizers have pulled together a toolkit to help you realize your vision, be it a solar-panel show-and-tell, an e-bike parade, or a clean energy rally turned block party. You can also tap one of the dozens of climate, justice, and grassroots groups that are core partners for the day of action, including 350.org, EcoMadres, Sierra Club, Solar United Neighbors, and Third Act, to see if they’re looking for Sun Day volunteers.

“We definitely will need everyone to be a part of this fight,” Shelly said. “Join us for Sun Day.”

Eager to hear more about Sun Day and the meteoric rise of clean energy? I’ll be interviewing McKibben about both in our discussion of his new book, “Here Comes the Sun.” Register to join us on Wednesday, Aug. 27, at 2:30 pm ET — and bring your questions!

The U.S. is still on track to build a record amount of new solar capacity this year, even as the Trump administration works to obstruct renewables.

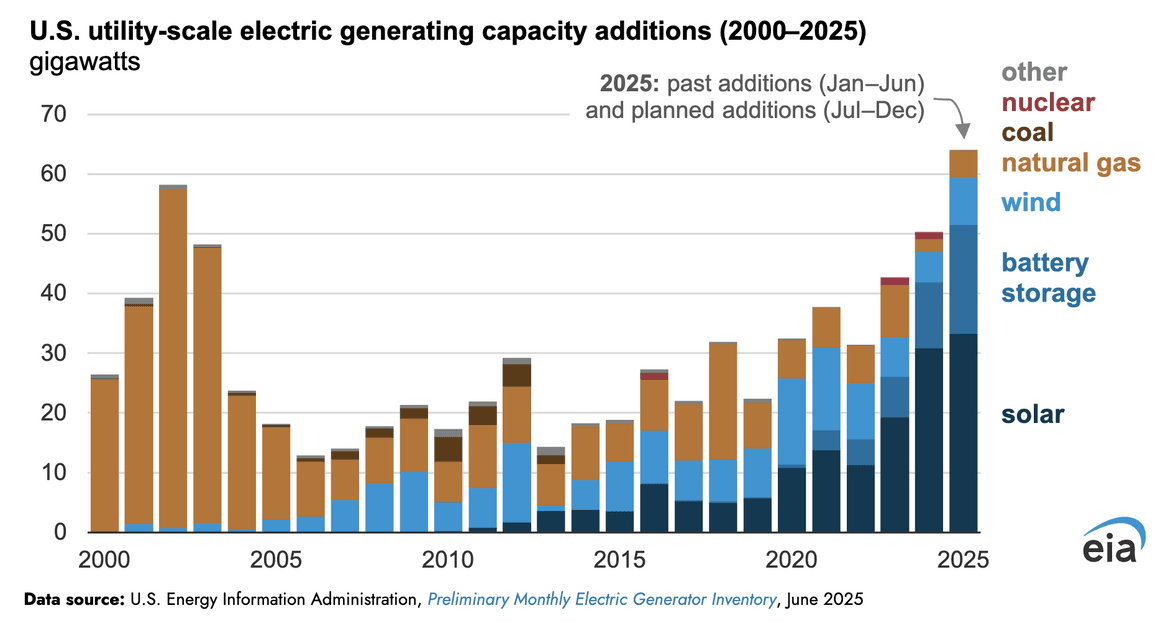

As it stands, the power industry is building more solar than any other type of power plant, which has been the case for several years running. Roughly 12 gigawatts of new solar capacity joined the grid in the first half of the year, and 21 gigawatts more are slated for completion by the end of the year, according to a recent survey by the federal Energy Information Administration.

Solar thus will contribute more than half of the expected 64 gigawatts of new power capacity additions this year. Adding in battery storage and wind installations, clean energy is on track to deliver 93% of new power-plant capacity this year, the EIA predicted in February. Moreover, 2025 could set the U.S. record for new power-plant construction, beating the 58 gigawatts added in 2002 at the height of a natural-gas plant boom.

Those facts reflect a set of hopeful trends: The U.S. is building power plants at a record pace; nearly all of those new plants will not emit carbon emissions; and, since renewables and batteries cost far less to operate than fossil fuel plants, they exert downward pressure on electricity costs. These are all good things to see at a time when demand for new power production is soaring — thanks to electrification, industrial growth, and an AI computing bubble — and consumers are grappling with steadily rising electricity rates.

Of course, these trends could prove short-lived, because the Trump administration is actively working to obstruct the buildout of clean and cheap energy.

This summer’s signature Republican domestic policy law targeted wind and solar with early termination of their tax credits, effectively raising the cost to deploy these types of power plants. The executive branch has sought to halt or inhibit offshore wind and renewable development on public lands. Simultaneously, the Trump administration is giving an artificial boost to fossil-fuel plants. The Department of Energy is invoking emergency powers to block the planned shutdown of the J.H. Cambpell coal-fired plant in Michigan, forcing customers to pay millions of dollars extra to preserve an outdated, uneconomical facility. Analysts fear the DOE could repeat this tactic with other uneconomic fossil-burning plants that are scheduled to retire.

Any clean power plants coming online this year were planned, permitted, and undergoing construction before Trump’s policy shifts took effect (though his officials have found ways to interrupt construction that was fully permitted, like the Empire Wind project off the coast of New York). In that sense, this year’s buildout offers the last snapshot of what it looks like when the electricity industry serves market demand with modern technologies absent active resistance from the U.S. government.

It’s still possible that momentum will carry the solar industry to another record year in 2026. Developers effectively need to start construction by the first half of 2026 to claim the full tax credit, and the administration recently tightened the longstanding tax rules on what counts as “starting,” further upping the pressure to get going. Historically, an impending tax-credit cliff incites a temporary rush to begin solar projects in time to qualify.

It will take a few years, then, for the Trump-era energy policies to fully remake the market landscape for solar. There’s little hope that the pace of gas-plant construction will match the current one for solar installations. Absent some reworking of U.S. energy policy, the country is heading for a time of decreasing power-plant construction just when we desperately need it to accelerate.

For years, anti-renewable-energy advocates have opposed solar and wind projects on the grounds that they take up too much land. Now those talking points, popularized by groups linked to the fossil-fuel industry, have made their way into a sweeping new directive from the Trump administration.

On Aug. 1, Interior Secretary Doug Burgum mandated that federal leasing decisions factor in “capacity density” for solar and wind projects.

His order defines “capacity density” as the amount of electricity a proposed facility is expected to produce, as a share of the maximum “nameplate” amount, divided by the site’s total acres. An appendix to the order shows that nuclear and combined-cycle gas plants rank highest on this measure, while renewables come in last.

The Interior Department will now have to consider the density measure in environmental reviews. With that in mind, the order questions whether the law allows any federal land use for wind and solar projects, “given these projects’ encumbrance on other land uses, as well as their disproportionate land use.”

Only a small portion of solar and wind projects are located on areas owned and managed by the U.S. government, but there is vast potential for development. A January 2025 report from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that 1,300 gigawatts of solar and 60 GW of onshore wind could be cost-effectively built on public lands, and that significant deployment in those spaces would be needed to meet grid-decarbonization goals.

It’s unclear whether the order might also block some projects on private property if they require reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act.

The directive is yet another example of the Trump administration’s push to slow the development of solar and wind, which together with batteries will account for more than 90% of new utility-scale energy-capacity additions this year. But more broadly, it illustrates how the administration is elevating fossil-fuel-backed misinformation about land use into federal energy policy.

“This is the latest sign that the Trump administration is really just relying on political talking points to push back on renewable energy that have little or no basis in fact,” said Dave Anderson, policy and communications manager for the Energy and Policy Institute, a watchdog group that focuses on the fossil-fuel and utility industries.

Before “capacity density” became a factor in federal leasing decisions, anti-renewable-energy groups were using the argument to build local opposition to utility-scale clean-power projects across the country.

The battle over a now-approved solar project in central Ohio provides a case in point.

In November 2023, a group called Knox Smart Development held a town-hall meeting to stoke opposition to the proposed 120-megawatt Frasier agrivoltaics project.

Canary Media (then the Energy News Network) confirmed last year that one of the main funders of the group was Tom Rastin, former vice president of Ariel Corp., which makes compressors for the oil and gas industry. Rastin and his wife, Karen Buchwald Wright, who is the company’s board chair, also play large roles in The Empowerment Alliance, a pro-natural-gas group.

Steve Goreham, a policy advisor to conservative think tank The Heartland Institute, was one of the speakers at the 2023 event.

In addition to denying that climate change requires a shift away from fossil fuels, Goreham told people at the Knox County meeting that solar farms require much more land than nuclear, gas, and coal-fired power plants. He also focused on “power density” in a 2023 opinion piece for the conservative-leaning Western Journal, warning that “environmental devastation” will result from policies that aim to accomplish net-zero carbon emissions. Goreham repeated this land-use argument in a Real Clear Energy post in March.

A Heartland Institute policy brief released this spring also relied on information about the land areas needed for solar and wind energy to conclude that large-scale electricity production from those sources “requires substantial ecological damage and impact.” The institute’s funders have included Exxon Mobil, coal-mining company Murray Energy (now American Consolidated Natural Resources), and foundations supported by the Koch brothers.

Another speaker at Knox Smart Development’s town hall, a lobbyist named Mitch Given, had previously represented The Empowerment Alliance in a 2023 presentation to the Ohio legislature’s Business First Caucus. His slides on the “nonsense of turning corn fields into solar fields” compared 6,050 acres for an Ohio solar project to just 5 acres for a similar-sized combined-cycle gas power plant.

A 2024 rally against the Frasier agrivoltaics project then brought in Robert Bryce, a former Manhattan Institute fellow who spent an entire chapter of his 2010 book arguing that wind and solar energy are not green because of their land use and power density. The argument is also featured in an anti-solar video he released this month.

The Manhattan Institute has received funding from fossil-fuel interests, such as Exxon Mobil and organizations linked to the Koch brothers. The Checks and Balances Project, a pro-clean-energy watchdog group, has criticized Bryce multiple times for failing to disclose those links. Bryce did not respond to Canary Media’s request for comment for this story.

“Everybody needs to come to this debate with a full picture of who they’re talking to and why they’re saying what they’re saying,” said Ray Locker, executive director for the Checks and Balances Project. Companies in the fossil-fuel industry “have a vested interest in preserving their business,” so when they present renewable energy “as somehow dirty, then that furthers their interest.”

This month’s Interior Department order is not the only recent federal attack on clean energy based on the land-use argument. Last week, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said that the agency’s longstanding Rural Energy for America Program would no longer fund large solar projects on “prime farmland,” a major shift for a program whose main use case has been helping farmers install solar energy.

Burgum’s order to the Department of the Interior is “really implementing an ideological agenda,” said Brendan Pierpont, director of electricity modeling at think tank Energy Innovation. In his view, the mandate’s definition of capacity density is an “absurd metric,” with multiple flaws.

Among other things, the capacity-density measurement does not capture the full picture of what it takes to produce electricity from a fossil-fueled or nuclear power plant.

The metric focuses only on the step where electricity is generated. A full life-cycle analysis would consider all stages for producing equipment, obtaining and transporting fuel, and dealing with waste. The Interior Department’s recent order is “entirely designed to make these [renewable] resources they don’t like look bad,” Pierpont said.

The definition of capacity density also fails to account for the fact that renewable projects can coexist with other activities, such as livestock grazing or farming certain crops, noted Matthias Fripp, global policy research director at Energy Innovation.

Additionally, land used for solar or wind energy can produce electricity for decades, he said, unlike fossil fuels, where the industry must “keep finding new land” for resource extraction. Researchers made a similar point in a 2016 study in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS One, which found the land requirements for coal-fired electricity could equal or exceed those for renewable energy within two to 31 years.

Anderson at the Energy and Policy Institute called the rationale for the Interior Department’s order “a red-herring argument to focus on just one of the impacts of different energy sources.”

Nowhere does the order address environmental and health concerns about mining for coal or uranium, drilling for oil and gas, or transporting and burning those fuels. Waste disposal, particularly for coal and nuclear plants, also poses a challenge.

Renewables “are obviously leaps and bounds ahead of fossil fuels in terms of their net benefits,” Anderson said.

Electricity costs are going up in the U.S. — and the Trump administration’s attempts to choke off clean energy development are only going to make matters worse.

The average price of electricity for residential consumers is set to hit 17 cents per kilowatt-hour this year and could climb to 18 cents per kilowatt-hour in 2026, per a new report from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Electricity prices are rising at more than twice the rate of inflation. Just five years ago, in 2020, average U.S. power prices were only 13.15 cents per kilowatt-hour — 23% lower than they are today.

The difference may seem small, but even one additional cent would tack on roughly $108 to the average U.S. home’s expenses each year. It’s taking a toll on people’s wallets: A survey conducted this spring found that three in four Americans said they’re worried about rising utility bills.

Republican leaders — most recently U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright — have tried to blame the trend on the large amounts of clean energy hitting the grid, but that’s not the problem. Solar, wind, and batteries are the cheapest form of power, and a 2024 report from research group Energy Innovation found no correlation between renewable energy adoption and utility rate increases.

Numerous reports and studies reveal that the core drivers of rising prices include an aging distribution grid that requires expensive repairs, and damage to the system from the wildfires and storms exacerbated by climate change. Then there’s the volatile price of natural gas, which produces about 40% of U.S. electricity. Skyrocketing demand for power is also increasingly a factor, as people electrify their homes, businesses, and cars, and in particular as data-center developers snap up as much energy as they can to support their AI ambitions.

In January, President Donald Trump took office promising a great many things — including to make energy more affordable. But since then, household electric bills have risen another 10%, and the policies he’s enacted are set to exacerbate the problems at hand.

Due to the GOP megalaw signed by Trump last month, the U.S. could install as much as 62% less clean energy over the next decade, per Rhodium Group estimates. That’s a huge deal: It’s expected that 93% of the new electricity capacity built this year will be solar, wind, or batteries.

If renewable energy construction slows at the same time data centers and consumers require more power, it will create a clear dynamic of too much demand and not enough supply. The result will be even higher energy bills for Americans, Rhodium and others forecast — the exact opposite of Trump’s grand vow to rein in costs.

If your power bills are getting higher and higher, you’re not alone. That’s probably little comfort, but here’s some proof anyway: Utilities requested or were granted a total of $29 billion in rate increases in the first half of 2025, according to a study from advocacy group PowerLines. That’s more than double the total in the same period last year.

The biggest reason for these rising prices stems from the piece of the grid you can see from your window, as Heatmap reports. Utility poles and wires, also known as the distribution grid, shuttle power from high-voltage transmission infrastructure into homes and businesses. Over the last few years, building and maintaining these lines has become the biggest source of costs that utilities recoup via power bills, according to a December report from the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab.

Natural disasters are also driving up expenses as they force utilities to repair and harden their grid for future weather events. California utilities, for instance, have to rebuild after wildfires and in some cases are spending even more money to underground lines. In the Southeast, utilities routinely look to raise rates to cover post-hurricane restoration costs.

Then there’s the fact that natural gas remains the U.S.’s dominant energy source and that prices for that fuel remain higher than they were over much of the last two years.

Now for the second big question: Will things get better anytime soon? Probably not, for a few reasons.

For starters, power demand is on the rise, stemming in large part from the construction of energy-hungry data centers. Tech giants plan to keep building facilities to run their AI operations, and how they’re powered — and how that demand is managed — could end up making everyone else’s electricity more expensive.

That demand could be largely satiated by new solar and wind farms, which are typically quicker and cheaper to stand up than fossil-fueled and especially nuclear power plants. But the One Big Beautiful Bill Act that Republicans passed in July will soon wipe out federal tax credits that incentivized clean energy construction.

Instead, the Trump administration is pushing to keep aging fossil-fuel power plants online past their retirement dates — a mission that could end up costing utility customers as much as $6 billion each year by the end of President Donald Trump’s term. A federal order that kept a Michigan coal plant open past its planned closure cost its operator $29 million in its first five weeks, and just this week the Energy Department reupped the facility’s extension until November.

Treasury rules tighten access to clean energy tax credits

The U.S. Treasury Department has released guidance that will make it harder to access wind and solar tax credits before their ultimate expiration, Canary Media’s Jeff St. John reports. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act gives wind and solar developers two options to tap the credits: They must either put their project in service by the end of 2027 or begin construction by July 2026. The Treasury’s new guidance narrows the federal government’s longstanding definition of what marks the start of construction.

Still, things could’ve been a lot worse, experts told Jeff — deadlines to finish work could’ve been accelerated, for example. And with these rules, developers have the clarity they’ve been waiting for to make decisions and get building.

USDA pulls support from solar, wind on farmland

Federal assistance for solar and wind power on farmland is fading. On Tuesday, the U.S. Agriculture Department announced that it will “no longer fund taxpayer dollars for solar panels on productive farmland or allow solar panels manufactured by foreign adversaries to be used in USDA projects.” It will also render wind and solar projects ineligible for the agency’s Business and Industry loan program, and bar Rural Energy for America Program loans from being used for ground-mounted solar projects larger than 50 kW.

The Trump administration has already taken multiple shots at REAP, Canary Media’s Kari Lydersen reported in July, freezing nearly $1 billion in funding for farmers and closing a window for new applications before it even opened.

“Come to America and lose $1B”: Foreign offshore wind developers have faced steep financial losses over the past few years, and they’ve only intensified under the Trump administration’s anti-wind policies. (Canary Media)

Polluting the post: Republican U.S. senators move to strip federal funding for the U.S. Postal Service’s transition to an EV fleet to save taxpayer money, though industry observers say the move would have the opposite effect. (Associated Press)

Steel’s dangerous warning: Last week’s fatal explosion at Pennsylvania’s Clairton Coke Works underscores the urgent need to decarbonize the coal-reliant steelmaking industry. (Canary Media)

Solar still rises: The Energy Information Administration estimates the U.S. will add 33 gigawatts of solar power to the grid this year, amounting to half of all new generation brought online in 2025. (EIA)

A red flag for gas stoves: A new Colorado law will require gas stoves to come with labels that warn buyers about the carcinogens and pollution the appliances emit, though a lawsuit has delayed its implementation for now. (Canary Media)

Cruising to electrification: New York City debuts its first hybrid-electric ferry, which is making trips from Manhattan to an emerging climate-change research hub on Governors Island. (Canary Media)

Counting on cleanup: California advocates worry Phillips 66 may shirk its responsibilities to clean up a “lake of hydrocarbons” that has accumulated under a Los Angeles-area refinery slated for closure later this year. (Capital & Main)

China’s dominance of the battery supply chain is uncontested. Many U.S. storage companies have tried to catch up by replicating the technologies already in mass production there. But a smaller cohort is taking a different tack: building factories for next-generation batteries that could give American manufacturers more of a competitive edge.

Peak Energy is one of the newest members of that cohort. The startup, which appeared on the scene in 2023, took a big step this summer when it shipped its first sodium-based grid-battery system for installation in the field. The 875-kilowatt/3.5-megawatt-hour battery is now being completed in Watkins, Colorado, at a testing facility known as the Solar Technology Acceleration Center.

In fairness, the battery cells were imported from China, but Peak designed and built a new enclosure for them in Burlingame, California. Since the sodium batteries are especially rugged, Peak could forgo the temperature-control equipment needed for the current favorite chemistry for grid storage, lithium ferrous phosphate (LFP). If this first installation works well and the cost savings are as consequential as promised, Peak plans to build U.S. manufacturing for the whole package, cells and all.

The installation is a rare bright spot as the storage industry at large grapples with the impacts of Trump administration energy policy. President Donald Trump’s unpredictably shifting tariffs on China have raised the costs of imported batteries and made it hard to plan. The White House’s signature budget law ripped up some — but not all — tax credits meant to support domestic manufacturing of batteries, and added dense new bureaucratic requirements around components from China. New investment in domestic clean-energy manufacturing has plummeted since Trump took office.

But the power sector still wants to build grid batteries at record pace, especially as supersized data centers clamor for electricity supply as soon as possible.

Upstart battery-makers often jockey over how much energy density they can pack into their cells, or how they can reduce the fire risks that follow from squeezing so much energy into a tight footprint. Peak Energy brags more about what its technology doesn’t need: heavy-duty climate control.

“If you think about it, an LFP [energy storage system] is essentially a giant refrigerator that has to operate flawlessly for 20 years in the desert,” said Cameron Dales, Peak’s chief commercial officer and cofounder. That’s because that particular chemistry ideally needs to stay within a few degrees of 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees Fahrenheit) to preserve its useful life; serious deviations from that safe zone could lead to declining performance or even dangerous failures. A handful of dramatic battery fires has already inspired community pushback against storage plants, making safety a crucial part of the industry’s social license. Indeed, this week U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin pledged to support communities resisting nearby battery installations.

The sodium-ion cells that Peak favors — technically called sodium iron pyrophosphate or NFPP — can withstand a much broader range of temperatures, from minus 20 degrees C (minus 4 degrees F) to 45 degrees C (113 degrees F). Peak’s engineers thus dispensed with the usual battery-cooling systems, relying instead on what Dales calls “clever engineering” around how the cells fit into the broader package. “There’s no moving parts, no fans, no liquids, no pumps, no nothing,” he said. The container does include a solid-state heater to ensure the cells never get too cold to charge.

This saves money by reducing the cost of materials and cutting auxiliary power usage up to 90% over the life of the project. But axing the conventional safety equipment brings one more major benefit, because that hardware has paradoxically caused several of the recent high-profile grid-battery fires (by, for example, erroneously spraying water on live batteries, which can make a fire where there wasn’t one).

Plenty of cleantech startups have pitched themselves as safer alternatives to dominant strains of lithium-ion batteries, only to be crushed mercilessly by the lithium-ion manufacturing juggernaut. Overwhelming scale and a wealth of industrial expertise keep pushing mainstream batteries to lower prices and superior performance. However, the up-front costs of the batteries themselves are now just a small piece of the overall bill.

“What has not really been addressed is the construction and installation of a project, and then, even more importantly, the long-term operating costs associated with running that power plant,” Dales said.

According to Dales’ calculations, the energy savings from the passive cooling of Peak Energy’s battery enclosure over a period of 20 years more than cover the initial cost of the battery cells. That’s one way to lure customers to a type of battery they haven’t seen before.

“How can a startup, who’s just getting up to speed and their costs are high and volume is not there yet, compete and win on a project like that?” he said. “It’s because these project economics are so good that even today, we can win on cost relative to … a Chinese LFP system.”

Flipping the switch on the Colorado project is just the start. Then Peak Energy needs to find paying customers interested in much bigger versions of the technology. But the startup has an innovative plan for that next step.

The founders of many battery startups focus on a technology that they find interesting (maybe they chose it for their doctoral research years ago), and then at some point have to convince customers to buy it. This typically leads to what Dales identified as “a classic failure mode, to get piloted to death.” The eager startup spends its precious time developing insignificant yet money-losing pilot installations with lukewarm customers, who try it for a few years and decline to make a follow-up purchase. Then the startup runs out of cash and collapses.

Peak Energy’s founders decided on a different strategy: develop a product in conversation with prospective customers, so they actually want to buy it when it’s ready.

The Colorado project, paid for by Peak, will be scrutinized by a consortium of nine utilities and independent power producers, who have signed on to receive exclusive performance data. If the project meets agreed-upon metrics, these companies will buy Peak’s product for their own use.

“If we do what we say we’re going to do, and the economics are what we think they are, then you should sign up for doing a real project, because it actually makes sense for you,” Dales explained. “That’s how these companies have entered the program, and now we’re in the ‘proof is in the pudding’ phase.”

Some of those consortium members have requested batteries for demonstration projects in 2026, in the storage range of 10 MWh to 50 MWh, Dales said. One large power developer is working on a 2027 project that would deploy nearly one gigawatt-hour of Peak’s sodium batteries to support a hyperscaler data center.

The path from initial installation to giga-scale projects always takes longer than battery startups initially pledge. In fact, only lithium-ion batteries have crossed that threshold, while more unusual variants languish in the minor leagues.

But Peak doesn’t have to invent the core technology — it’s piggybacking off an emerging field of China’s battery industry — and it’s coming to market at a time of propulsive growth in grid storage demand. Its task might not be quite so daunting as it has been for other battery innovators.

California’s premier “virtual power plant” program is already reducing the state’s reliance on polluting, costly fossil-fueled power plants. And that’s just the start of what the scattered network of solar and batteries could do to stymie rising utility costs — if the state Legislature can stave off funding cuts to the program, that is.

So finds a new analysis from consultancy The Brattle Group on the potential of the statewide Demand Side Grid Support (DSGS) program to help California’s stressed-out grid keep up with growing electricity demand. The program pays households and businesses that already own solar panels and batteries to send their stored-up clean power back to the grid during times of peak demand, like hot summer evenings.

Continuing the program’s payments to those customers to make their stored energy available could save all California utility customers anywhere from $28 million to $206 million over the next four years, the report found.

The findings come as state lawmakers attempt to rescue the DSGS program from a new round of funding cuts. Last year, California lawmakers slashed DSGS spending to deal with an unexpected budget shortfall. The situation is still troubled this year, and Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom has proposed defunding the program further, leaving it little money to pay participants beyond this year.

But the program could regain its financial footing if newly introduced legislation becomes law.

This week, California Assemblymember Jacqui Irwin, a Democrat, released draft legislation that would allocate money to DSGS from the state’s much-contested Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, which is supported by payments from polluting companies. That draft legislation calls for depositing 5% of revenue collected by electric utilities for that fund into a new account to finance DSGS from 2026 to 2034. Lawmakers don’t have much time to move the proposal forward, with the state’s legislative session ending Sept. 12.

Saving the program would be a win for reducing the state’s sky-high utility costs, according to Ryan Hledik, a principal at Brattle and coauthor of the report. “It’s cheaper to pay customers to provide grid resources from technology they’ve already adopted than it is to go invest capital in new stuff,” he said, including the fossil-fueled generators now used to meet peak grid needs.

California has already committed billions of dollars on emergency backup generators and on keeping aging fossil-gas-fired power plants open past their planned closure dates, he noted. The high end of the savings DSGS could provide is based on the assumption that it “would be a substitute for spending money on more expensive emergency resources,” he said.

At the same time, DSGS could also bring down the “resource adequacy” payments shelled out by California utilities, community choice aggregators, and other power providers to secure enough grid resources to meet peak demand in future years. Those costs have been rising in California, though not as drastically as they have in other parts of the country.

Since its launch in 2023, the battery program Brattle analyzed, which is one of the four options for customers to participate in DSGS, has grown to a collective 700 megawatts of capacity. The report forecasts the program could nearly double its current capacity to reach 1.3 gigawatts by 2028, covering roughly half the total residential distributed-battery capacity expected to be online in the state by then.

That won’t happen without state funding for the program, however — and though some state lawmakers are attempting to save DSGS’s funding, it remains unclear if the money will be there for future years.

If Irwin’s proposed provision becomes law, it would supply roughly $70 million to $90 million per year to DSGS over the next five years, said Brad Heavner, executive director of the California Solar and Storage Association. DSGS needs at least $75 million this year to operate in 2026, according to a letter sent to California lawmakers on Tuesday by 35 companies, trade groups, and advocacy organizations active in solar, batteries, on-site generators, and demand response, including Heavner’s group.

The amount of funding dedicated under the proposed legislation “won’t be enough for all the program activity we expect — but it will be enough to have a core program,” he said.

DSGS’s cost-effectiveness, demonstrated by the Brattle analysis, should give lawmakers confidence that the money isn’t being wasted, Heavner said. “It’s great that the Brattle study finds there’s a two-for-one benefit — every dollar spent here saves two dollars” for utility customers across the state, he said.

Brattle’s research was funded by Sunrun and Tesla, two companies with longtime programs that sign up customers to make their excess battery capacity available for grid services. Both firms benefit from initiatives that boost the value of the rooftop solar and battery systems they sell to households in California and beyond.

But the study also matches broader research on how virtual power plants can reduce blackout risks and electricity price spikes on U.S. grids. VPPs are collections of homes and businesses with smart thermostats, grid-responsive EV chargers, water heaters, and other appliances that can reduce how much power they’re using, as well as rooftop solar-charged batteries or generators that can push power back to the grid as needed.

Under the Biden administration, the U.S. Department of Energy found that the hundreds of billions of dollars that consumers spend on EVs, rooftop solar systems, batteries, smart thermostats, and other appliances could provide 80 to 160 gigawatts of VPP capacity by 2030, enough to meet 10% to 20% of U.S. peak grid needs and save about $10 billion in annual utility costs. (The Trump administration has removed this DOE report from the internet, but archived versions are available.)

VPPs also pass the eye test: They’ve helped avoid blackouts in Puerto Rico, New England, and California this summer. States including Colorado and Virginia have passed laws or created regulations requiring utilities to expand VPPs.

DSGS, for its part, has “scaled in a way that folks can no longer poke holes in its reliability,” said Lauren Nevitt, Sunrun’s senior director of public policy. Sunrun has dispatched hundreds of megawatts from its customers’ batteries in California so far this summer, all during hours of the evening when wholesale electricity prices spike above $200 per megawatt-hour.

In a two-hour experiment last month, Sunrun and Tesla dispatched 535 megawatts of battery power to the grid in what utility Pacific Gas & Electric called “the largest test of its kind ever done in California — and maybe the world.”

Lining up a steady source of funding for years to come would give these participating companies confidence that their investments in DSGS won’t be left stranded by future budget cuts, Heavner said — and encourage even more investment going forward.

Pressure to curb energy costs is particularly acute in California, where residential customers of the state’s three major utilities now pay roughly twice the national average for their power and where rates rose 47% from 2019 to 2023.

It is also among the best-positioned states to take advantage of VPPs to rein in those costs. California leads the country in rooftop solar, backup battery, and EV adoption, and a 2024 Brattle analysis found that VPPs could provide more than 15% of the state’s peak grid demand by 2035, delivering $550 million in annual utility customer savings.

DSGS is only one of a number of VPP options available in California. But advocates say it’s by far the most successful in a state that’s seen mixed progress on VPPs to date. In the past five years, stop-and-start policies from the California Public Utilities Commission have reduced overall capacity from demand-response programs that pay utility customers to turn down their electricity use to relieve grid stress.

DSGS, which is run by the California Energy Commission, has grown rapidly due to a combination of factors, said Edson Perez, who leads California legislative and political engagement for clean-energy trade group Advanced Energy United. It’s available to residents across the state, rather than being limited to individual utility territories and programs. It also has relatively simple enrollment and participation rules compared to many other programs, he said.

It can be tricky to quantify the costs and benefits of these kinds of programs compared to traditional utility investments in power plants or large-scale solar and battery systems. But Brattle’s new report is the “first analysis of what its value is out in the field,” he said, and the results show “it’s very cost-effective.”

Solar-charged batteries are also much less polluting than the state’s other emergency grid-relief resources, he said. DSGS is one of a set of emergency programs launched after California experienced rolling blackouts during summer heat waves in 2020 and more heat-wave-driven grid emergencies in 2022.

But most of the billions of dollars in emergency funding have gone to fossil-fueled generators. California had spent about $443 million on state-managed generators that burn fossil gas or diesel fuel as of December 2024, and has committed about $1.2 billion to keep fossil-gas-fired “peaker” plants in Southern California open until 2026, well past their scheduled 2020 closure date.

“We’re in a statewide affordability crisis,” Perez said. “Leveraging existing resources out there drives down costs for everyone.”

The Trump administration has extended its order to keep a Michigan coal-fired power plant running until November, well past its planned closure in the spring. It’s the latest move in a push to force dirty, expensive power plants to keep operating, which experts warn could saddle Americans with billions of dollars in unnecessary electricity costs.

Just days before the J.H. Campbell plant was set to shutter in May, the administration ordered it to stay open for 90 days — an unprecedented federal intervention in state-regulated utility operations. That order has already cost Midwest utility customers millions, and Michigan’s top utility regulator estimates that keeping the aging plant open longer could burden consumers with more than $100 million in unnecessary costs.

The Department of Energy’s Wednesday extension adds weight to concerns from states, environmental advocates, and clean-energy industry groups that the administration intends to wield emergency powers meant to address true threats to grid reliability to prevent any fossil-fueled power plant from closing nationwide. Doing so would cost consumers between $3 billion and nearly $6 billion per year by the end of President Donald Trump’s term, per an August report from consultancy Grid Strategies.

“The order purports to override the considered judgment and careful work of many federal, state, and regional bodies who actually have authority to keep the lights on,” Michael Lenoff, senior attorney for nonprofit Earthjustice, said in a Thursday statement.

Lenoff is leading litigation against the DOE’s initial order from May. Michigan’s Attorney General Dana Nessel has also challenged that order in court, after the agency failed to respond to requests from environmental groups and eight state utility commissions seeking a rehearing of the decision.

To keep fossil-fueled plants running, the Trump administration is taking advantage of Section 202(c) of the Federal Power Act, which gives the DOE the authority to take temporary action to address nearterm grid-reliability emergencies. But many groups say there is no such crisis: Wednesday’s order from Energy Secretary Chris Wright, a former gas industry executive and well-known denier of the climate-change crisis, “points to no evidence of an imminent emergency requiring Campbell to keep racking up the bills paid by customers in Michigan and nearby states,” Lenoff said.

“Despite already forcing the plant to run for 90 days, [Wright] points to not a single instance where the plant was needed to keep the lights on,” Lenoff said.

Consumers Energy, the utility that owns J.H. Campbell, reported in late July that it cost $29 million to operate the plant in the first five weeks of the DOE’s stay-open order.

“The coal-fired J.H. Campbell plant has reached the end of its life. Michigan cannot afford to let political interference prolong its operation,” Justin Carpenter, policy director for the Michigan Energy Innovation Business Council, said in a Thursday statement. “So-called temporary extensions only keep an unnecessary, inefficient plant alive, extending its pollution and high costs.”

Later in May, the DOE also used its Section 202(c) authority to order the Eddystone oil- and gas-burning plant in Pennsylvania to stay open through the summer. It was set to close this year too, and, as with the J.H. Campbell plant, utility regulators and regional grid operators had determined that shutting it down would not threaten grid reliability. The DOE’s 90-day order for the Eddystone plant is set to expire in late August.

Lawmakers, advocates, and industry experts are increasingly concerned that the Trump administration intends to apply its Section 202(c) authority more broadly. In particular, critics fear a DOE report issued in July will be used to justify future orders — even though its methodology is severely flawed.

The document was written to comply with an April executive order from Trump that tasks the agency with taking unilateral authority over power-plant closures, circumventing decades-old structures that utilities, state and federal regulators, and regional grid operators follow to determine when power plants can close or when they must stay open.

Earlier this month, clean-energy trade groups and nine Democrat-led states filed rehearing requests with the DOE asking it to redo the July grid-reliability report. They argue the study uses cherry-picked data and flawed assumptions to declare that the U.S. faces a hundredfold increase in grid blackout risks absent federal intervention in power plant operations.

Running aging power plants is expensive for utility customers, both in terms of direct costs on energy bills and the indirect costs of crowding out new, cheaper renewables. Utilities and independent energy developers will build less solar, batteries, and wind power if those plants stay online.

The DOE’s moves come as electricity prices are rising at more than twice the rate of inflation across the country. Wright and Trump have falsely claimed that renewable energy is to blame for that trend.

“By illegally extending this sham emergency order, Donald Trump and Chris Wright are costing hardworking Americans more money every single day for a coal plant that is unnecessary, deadly, and extremely expensive,” Laurie Williams, director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign, said in a Thursday statement. “While Donald Trump and Chris Wright decry this made-up ‘energy emergency,’ they are simultaneously limiting our access to cheap, reliable, renewable energy.”