Bone-chilling cold and Arctic winds gripped the northeastern U.S. over the past few weeks, straining electricity systems and raising power prices as people cranked up their heat. Now, as the region finally starts to thaw, early data shows how America’s offshore wind farms helped keep electricity flowing during the extreme-weather stretch.

The results demonstrate the bitter irony of the Trump administration’s ongoing — and potentially unlawful — battle against U.S. offshore wind development. Federal officials are calling for additional fossil-fueled power to prevent future winter blackouts, all while trying to block the build-out of offshore wind, one of the most valuable resources for cold-climate coastal states.

“Performance data is showing in real time that offshore wind delivers reliable power when the grid needs it the most … at the scale this region and our country need,” said Liz Burdock, president and CEO of Oceantic Network, which advocates for marine renewable energy sectors.

Burdock was speaking on Tuesday in New York City at the group’s annual International Partnering Forum, where hundreds of offshore wind developers, policy experts, and labor leaders gathered to regroup following President Donald Trump’s yearlong attacks on five in-progress offshore wind farms.

For years, independent energy experts have forecast that offshore wind could deliver substantial amounts of power to densely populated, land-constrained communities along America’s east coast — particularly during winter cold spells, when demand for fossil gas exceeds supply. And grid operators in the region have been banking on offshore wind capacity to come online to meet the rising electricity needs of data centers and electrified homes and vehicles.

The data from January shows that the nation’s two operating utility-scale offshore wind farms — South Fork Wind and Vineyard Wind — performed as well as gas-fired power plants and better than coal-fired facilities, including during last month’s Winter Storm Fern, experts said at the event.

The 132-megawatt South Fork Wind farm, which delivers power to Long Island, New York, had a “capacity factor” of 52% last month. The metric reflects how much electricity the project actually generated compared with the maximum amount it could generate in a given period. That puts South Fork Wind on par with New York state’s most efficient gas plants.

“The wind capacity in the Northeast is absolutely amazing, particularly over the winter,” said Mikkel Mæhlisen, vice president of the Americas Generation division for Ørsted, which jointly owns South Fork Wind with Skyborn Renewables.

The 12-turbine project became America’s first utility-scale offshore wind farm in 2024, when it started providing power to some 70,000 homes. Last winter, it was also a beacon of reliability, notching a 54% capacity factor between December 2024 and March 2025.

Vineyard Wind, meanwhile, can already produce as much as 600 MW of clean electricity off the coast of Massachusetts. The project, which is 95% complete, is one of the five offshore wind farms that were forced to halt construction late last year in response to Trump’s stop-work orders, which cited ambiguous “national security” concerns. Federal judges have allowed all five projects to proceed as the developers’ complaints move through the legal system.

However, Interior Secretary Doug Burgum says the Trump administration plans to appeal those court rulings, Bloomberg reported on Wednesday.

During Winter Storm Fern, Vineyard Wind had a 75% capacity factor, Burdock said. Once fully operational, the project will deliver power at a price of $84.23 per megawatt-hour to the New England grid. That’s markedly less than spot wholesale prices during the storm, which spiked to over $870 per MWh on Jan. 25.

Soaring gas prices and limited supplies pushed utilities in New England to fire up oil-burning power plants in order to avert blackouts, assets that are typically too expensive to justify running. The result will be even higher bills for the region’s residents, who have historically faced some of the highest energy costs in the nation — in part because New England lacks recoverable resources like oil and gas, said Katie Dykes, commissioner of Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection.

Having a more diverse energy mix would help states reduce their reliance on firm, dispatchable, but also costly and dirty power plants during such challenging periods.

“Variable resources like wind and solar, when they’re operating during these cold weather periods, they’re actually helping to keep a lid on prices,” Dykes said during a panel. “It means we can reduce the runtimes of those more expensive oil units. It also means that we can preserve the runtime of those [fossil] resources that are relying on stored fuel.”

Proponents of America’s nascent offshore wind industry said they’re hopeful the five in-progress projects will be completed as planned. In New York, Ørsted’s Sunrise Wind and Equinor’s Empire Wind would together provide 1.7 gigawatts of new capacity — enough to meet more than 10% of the electricity needs in New York City and Long Island.

“The last few weeks have been extremely stressful,” Gary Stephenson, a senior vice president for the Long Island Power Authority, said about the region’s cold snap. The municipal utility, which serves 1.2 million customers, purchases power from South Fork Wind and will connect its grid to Sunrise Wind, which is expected to start operating in 2027.

“I really wish we had that Sunrise facility online. That would have taken so much pressure off the natural gas system,” Stephenson said at the event. “So we’re looking forward to that [coming online] towards the end of next year.”

A correction was made on Feb. 12, 2026: This story originally said Vineyard Wind delivered power at $84.23 per megawatt-hour during Winter Storm Fern, but that is the price the installation will deliver once fully operational.

Canary Media’s “Electrified Life” column shares real-world tales, tips, and insights to demystify what individuals can do to shift their homes and lives to clean electric power.

As Winter Storm Fern was dumping record amounts of snow and ice across the U.S. a couple of weeks ago, Kit Wu sprang into action.

Wu, the founder of the Boston-based heat-pump installation and research startup Laminar Collective, quickly reached out to his customers. He wanted to know how the more than 70 households his startup had installed heat pumps for were faring — and to address any performance issues that might have come up as the city weathered its eighth-biggest snowstorm in history.

The vast majority of heat pumps fared well, Wu’s customers reported. Even as Fern eventually departed and a brutal cold snap gripped the region, more than 90% of heat pump units held up without a hitch. But six did struggle.

Their owners saw dips in indoor temperatures and sent Wu photos of their outdoor units, the parts of heat pump systems that find warmth in even frigid winter air. These appliances had a significant buildup of ice on their backs — up to a half inch thick.

That wasn’t good.

Heat pumps, which provide both heating and cooling, use finned metal coils filled with refrigerant to extract thermal energy from the atmosphere. A stubborn crust of ice throttles airflow, making it tough for a heat pump to scrounge up enough heat to keep residents toasty, Wu explained.

For years, heat pumps have been popular in the warmer U.S. South, but not so much in chillier parts of the country. That’s changing. Tech improvements have made it possible for households in colder climes to embrace the appliances, which are always better for air quality and often cheaper to run than fossil-fueled boilers and furnaces. Even in notoriously frosty states like Maine, they’re taking off.

But with this new territory comes new challenges. While some heat pumps are designed to work in temperatures as low as minus 22 degrees, it’s possible for extreme, prolonged winter weather to dampen their efficiency.

That’s exactly what happened with the struggling heat pumps that Wu encountered: They had accumulated so much ice that they just “couldn’t keep up,” he said.

Thankfully, these challenges are surmountable. Wu was able to return each of the iced-over units to smooth working order in one visit. But it would have been better to avoid the issue in the first place. Here are a few steps you can take to help your heat pump perform at its best even on the worst winter days.

To keep your heat pump humming along in the freezing cold, bring in a heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning technician before the bad weather comes, said Mark Kasdorf, founder and CEO of Forge, a heat-pump installer based in Newton, Massachusetts.

“I think 99% of all issues can be taken care of by just having an expert take a look at the system,” he said.

A professional can perform what’s called a blower-door test to find any big air leaks in your home, which work against a heat pump. And have the technician check for blocked air filters — or do it yourself — particularly if you bought the home with the heat pump already installed.

“Tons of homeowners never change their filters,” Kasdorf noted, even though it’s something most can do on their own. Helpful YouTubers have demonstrated the process for both ductless and ducted systems.

You’ll want to give your heat pump space to breathe, with at least two feet of clearance. If snow or fallen leaves are common in your area, make sure your heat pump is raised off the ground. The appliance needs this space so that, when it goes into defrost mode, water can efficiently drain away, rather than refreeze into ice.

When snow is coming down hard, break out the shovel, Wu added. “If you’re going to dig out your car, you should also dig out your heat pump.”

You could even get a little awning or semi-enclosed hut for your system to give it extra protection from a storm.

A suffocated heat pump is a sad heat pump.

A layer of ice will cause it to run less efficiently and jack up your energy bills. But there are a couple of remedies you could try, Wu said.

One is to run the heat pump in reverse in cooling mode. That will heat up the coils, potentially allowing them to thaw their icy coats.

Another is a manual defrost: pouring room-temperature water over the ice. This trick worked on all the units that he recently tended to, Wu said.

Never use hot water, though, he noted; the metal could crack.

I’ll admit, I was a bit skeptical of this piece of advice. But Kasdorf insisted it has worked for him, so here goes.

If your appliance isn’t pumping out enough heat, then take a picture of the unit, upload it to an AI model — Gemini has worked best for Kasdorf — and describe the weather and your issue.

A large-language model can suggest quick fixes. When I gave Gemini a test case, it offered some of the strategies in this article, as well as warned me to resist the urge to chip at the ice with a sharp object. A misplaced stab could cause a refrigerant leak that takes the heat pump out of commission.

Treat the tool “like a really smart uncle” who’s an HVAC technician, Kasdorf said; the voluble advice may be helpful, if imperfect. It’s also best to think of this exchange as a starting point for some troubleshooting. If it provides anything that seems especially involved — or just weird — call a professional, he noted. And if your problems persist, the same applies: Work with your installer.

That is, after all, what Wu’s customers did, and the results speak for themselves.

Last Friday, 10 days after Fern swept through Boston, area temperatures were still well below freezing, and Wu could see snow piled high outside. But after the simple fixes he employed, every one of his customers’ heat-pump systems was working just fine.

Want more tips on keeping your heat pump humming even in extreme weather? Efficiency Maine has a plethora.

Startup NineDot Energy just raised $431 million to build batteries in New York City’s vacant nooks and crannies — an endeavor that will help the metropolis fend off looming electricity shortages.

The debt financing announced Monday will support the Brooklyn firm’s plan to develop 28 battery projects totaling 494 megawatt-hours of energy storage capacity over the next two years. NineDot estimates that’s enough storage to meet the peak energy needs of about 100,000 households.

NineDot is one of several companies deploying “community battery systems” — grid-tied energy storage installations that can fit into roughly an acre of land or less — in New York City. These systems sop up excess energy from the grid when power is abundant and send it back when demand is high, like on hot summer afternoons when millions of air conditioners crank up. Bigger batteries may be able to store more energy, but community-scale systems can be more realistic to quickly deploy in über-dense places.

The decade-old startup’s latest round of construction finance, led by Natixis Corporate & Investment Banking, brings its total funding to just over $1 billion, said David Arfin, NineDot’s CEO and co-founder.

NineDot already has seven projects operating — including a 12-megawatt-hour battery and solar installation at a former parking lot in the Bronx and a 20-megawatt-hour battery system in Staten Island — or in advanced stages of construction in New York City, he said. By 2028, it plans to have 37 community storage systems with a combined capacity of 1.6 gigawatt-hours up and running across the five boroughs, he said.

It isn’t easy to find spots to build batteries in New York City, said Adam Cohen, NineDot’s chief technology officer and co-founder. It can be even harder to find space on Con Edison’s power grid to connect them, he said.

But the utility is under mounting pressure to expand its energy storage capacity — and that’s driving companies like NineDot to seek out vacant or underused lots in the country’s densest urban environment.

New York law sets a statewide goal of 70% renewable electricity by 2030, and state policy calls for building 6 gigawatts of energy storage by 2030. Upstate New York has plenty of land for utility-scale wind, solar, and battery farms. But downstate New York and New York City are where power demand is greatest and the generation mix is the dirtiest — and there’s not yet enough transmission grid capacity to solve those problems with clean power from the north, Cohen said.

Meanwhile, the New York City area faces an energy crunch as power demand surges and aging fossil-fueled plants in the boroughs prepare to shutter. In October, the state’s grid operator warned that New York City and Long Island might face “reliability violations” as soon as this summer.

Late last year, state regulators ordered Con Edison to seek out “a broad array of potential non-emitting solutions” that could quickly bolster reliability.

“You could solve that with new transmission,” Cohen said — except that’s hard to build. The Champlain Hudson Power Express, a major transmission line from Canada to New York City, is nearing completion and scheduled to start delivering hydropower and wind power in May. But another major transmission line being planned to carry power into the city was canceled in 2024.

Another option is “keeping dirty peaker plants online,” Cohen said. But the fossil-fueled plants that New York City relies on to serve its peak loads are expensive to operate and emit health-harming air pollutants, largely in low-income communities and communities of color.

That’s why state regulators’ order to Con Edison calls for “non-emitting solutions, prioritizing cost-effectiveness and ease of deployment, and minimizing impacts to disadvantaged communities.”

Batteries fit that bill, say proponents of the tech. William Acker, executive director of the New York Battery and Energy Storage Technology Consortium, noted that the utility’s initial report to regulators in January identified a roughly 125-megawatt shortfall for about three hours during peak summer demand starting in 2032. This is “well within the range of the energy storage we expect to be deployed,” he said.

“That’s changing how the state is looking at energy storage deployment in New York City,” Acker said. “It’s one of the most cost-effective ways to address this reliability challenge.”

New York state has struggled to meet its targets for utility-scale clean energy, with supply chain disruptions and rising interest rates undermining the financial prospects for big wind and solar farms. It’s also faced challenges in getting large-scale battery projects up and running, largely because of problematic contract structures that crimped project financing.

But smaller community battery projects, like NineDot’s, have an advantage on that front: They can access the state’s incentives designed to encourage distributed energy resources that deliver power when and where the grid needs it the most. These incentives offer far steadier and more predictable revenue streams than those set up for the state’s larger-scale utility programs, Arfin said.

Community battery projects are also eligible to feed into New York’s Statewide Solar for All program, which provides a portion of revenues from community solar and storage projects to utility customers in disadvantaged communities who are enrolled in energy-affordability programs. NineDot forecasts that the projects it has committed to Statewide Solar for All will deliver more than $60 million in energy credits over the coming decade.

NineDot’s strategy of putting batteries on vacant or underutilized lots is one of several approaches being taken to add energy storage to the New York City grid. For example, Con Edison has deployed batteries at its substations and worked with companies installing them at EV charging stations and electric school bus depots. And some New York City businesses are using small plug-in batteries to cushion their draw on grid power during hours of peak demand.

Meanwhile, larger-scale projects like 174 Power Global’s 400-megawatt-hour battery in Queens are starting to get built, and energy developers, including Summit Ridge Energy and Convergent Energy and Power, have community battery projects underway.

But batteries in the Big Apple aren’t always getting a warm reception from their neighbors. Public opposition, spurred by a spate of grid battery fires, has quashed several projects in Staten Island and has led to an ongoing moratorium on their construction in the Long Island town of Oyster Bay. New York City mayoral candidate Curtis Sliwa railed against battery projects in the waning days of his campaign last year, calling them “mini-Chernobyls.”

But Cohen noted that the Fire Department of New York has spent years developing grid-battery safety rules that may be the most comprehensive in the country. “The FDNY is the global gold standard for approving battery storage technology and sites,” he said. “It’s cumbersome — but it’s trusted and thorough.”

As the Trump administration promotes U.S. natural gas exports, federal analysts warn that shipping massive volumes abroad could raise costs for consumers at home.

The fracking revolution unleashed abundant natural gas in the early 2010s, lowering costs for heating and enabling gas-fired power production to unseat coal as the top electricity source in the United States.

Now, though, homes and power plants compete with a new and growing source of gas consumption: liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals, gargantuan facilities that compress and ship gas to buyers overseas. Eight terminals currently export gas from U.S. shores, sucking up more than all 74 million households on the domestic gas network do. Counting those terminals and pipelines that carry the fossil fuel to Canada and Mexico, the U.S. exports more than 20% of its gas production.

LNG facilities generate immense revenue for the companies that build and supply them, but they come with considerable environmental and climate impacts. The export infrastructure justifies even more fossil-fuel extraction at a time of record U.S. production, and the energy-intensive process required to liquefy, ship, and regasify the fuel releases far more carbon than simply burning gas. Depending on how much of the gas leaks along the way, the fuel can be as bad as coal in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

After a few years of just continuing with the status quo on LNG policy — that is, expand, expand, expand — the Biden administration in January 2024 paused approval of new terminals so that it could rethink how the U.S. evaluates their impacts.

President Donald Trump undid that pause right after taking office last year, as part of a wide-ranging assault on federal climate policies. Now, as the U.S. finds itself in the grip of an affordability crisis, it’s not LNG’s climate implications that have taken center stage but its threat of driving up domestic energy prices when utility rates are already reaching record highs.

Last year was clearly an up year for natural gas prices, which jumped by 56% from a record low in 2024, landing at an annual average of $3.52 per million British thermal units at the Henry Hub, which sets the benchmark gas price. The Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration expects gas prices to stay nearly flat this year but to soar to about $4.60 in 2027. The reason: “because growth in demand — led by expanding liquefied natural gas exports and more natural gas consumption in the electric power sector — will outpace production growth.”

Trump vehemently supports LNG expansion and has pressured foreign leaders to buy more U.S. gas. But even without new approvals, federal regulators from previous administrations have already confirmed enough LNG expansion to double export capacity by 2029. If that trend elevates gas prices, for the reasons the EIA described, it could indeed end up saddling consumers with even higher energy costs.

Over the past year, gas power prices rose enough that coal staged a limited comeback in power markets. This pushed total U.S. carbon emissions up for the year and contributed to electricity bills rising faster than inflation.

“We have exited the era of low natural gas prices and have entered the era of higher gas prices,” said Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program at consumer advocacy group Public Citizen. “The only outcome here is a far more expensive domestic energy bill for Americans.”

Gas advocates, however, reject the view that significantly higher prices are inevitable and argue that LNG exports have grown considerably without a correlated rise in price.

Since 2016, LNG exports have ascended to 15 billion cubic feet per day without a steady year-over-year increase in domestic gas costs. Henry Hub prices rose in 2021 as the economy revived from its Covid-19 torpor and Winter Storm Uri shocked the Texas market. Prices spiked in 2022 after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Europe’s subsequent scramble for non-Russian gas. Then U.S. prices fell below $3.

If gas companies boost production in anticipation of next year’s rising demand, the price escalation predicted by the EIA may not materialize, said Richard Meyer, vice president of energy markets, analysis, and standards for the American Gas Association, which represents gas utilities.

“High prices are never a foregone conclusion — it’s all about the market balance,” Meyer said. “The industry is actually being quite responsive to the price signals.”

As a case in point, he noted that the EIA’s short-term outlook throughout 2025 predicted that gas prices would rise in 2026. Now, 2026 is here, and EIA predicts a 2% annual decrease. If the same dynamic unfolds this year, then the expected price hike in 2027 could vanish, too, as producers drill more to meet demand.

Indeed, when companies are spending $10 billion to $15 billion to build an LNG terminal, they typically secure dedicated gas and pipeline capacity, said Jacques Rousseau, managing director for global oil and gas at the independent data firm ClearView Energy Partners.

“They have all the pieces of the puzzle lined up,” Rousseau said. “LNG companies primarily source gas from new pipeline capacity, since it needs to connect directly with their liquefaction facilities.”

Slocum of Public Citizen, for his part, acknowledges that past LNG expansion was met with more domestic production, but that “production will be challenged to keep up” with the impending demand growth.

After all, it’s not hard to imagine a late-2020s scenario in which AI computing prompts a surge in gas power production just as LNG shipments balloon. New gas exploration could be constrained temporarily — if, say, investment funds dry up or pipeline projects get delayed. Wall Street has already been pushing gas companies to focus on “capital discipline and dividends,” putting a damper on investment in new production, Rousseau noted. Should some constellation of those forces align, a gap could open up between gas supply and demand, sparking the kind of price hikes the EIA is warning about.

Electric utilities can protect their customers from soaring gas prices by diversifying to more wind, solar, and battery power. Slocum, meanwhile, wants the federal government to protect people from higher energy bills by more assertively regulating gas exports.

Per the Natural Gas Act of 1938, companies can build LNG terminals only if the DOE confirms that doing so is in the “public interest.” And while the government has exercised its regulatory power before a terminal gets built — after which the terminal can ship its approved capacity for 25 years — Slocum says that the DOE can and should also put guardrails on export volumes to respond to evolving circumstances.

“There needs to be actual regulation, where the Department of Energy says it’s a conditional approval subject to revision if Henry Hub or other key benchmarks exceed a certain price,” Slocum said. The regulation could blunt the impact of a future international crisis that pulls gas supply away from the U.S. and spikes prices for domestic consumers.

The idea has some populist appeal. But then again, Slocum noted, Republicans in Congress have been proposing even less regulation — in fact, they want to eliminate the public-interest determination altogether.

Some members of the oil and gas industry have a less-caveated stance on the whole question. In the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank’s December pulse check on the industry, one executive from an exploration and production firm expressed hopes that the Fed would cut interest rates, thereby boosting the economy.

Then, the respondent commented approvingly, “new pipeline projects will improve takeaway from West Texas, and new LNG plants will help to drive natural gas prices upward.”

When I first met John Holbrook at his office in northeastern Kentucky, the region seemed to be on the cusp of a revival. It was a scorching summer day in 2024, and Century Aluminum was considering building an enormous smelter in this corner of Appalachia — one that would create thousands of jobs in an area where employment was steadily drying up.

Holbrook, who heads the Tri-State Building and Construction Trades Council, called the $5 billion project a “life-changing” opportunity. He’d joined a coalition of labor organizers, environmentalists, and local officials who supported Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear’s attempt to hammer out an agreement to supply Century’s new smelter with clean electricity.

Two weeks ago, Century finally announced its plans. The Chicago-based manufacturer said it will build an aluminum plant in Oklahoma instead, in partnership with Emirates Global Aluminium. The jointly developed facility will be America’s first new smelter since 1980 — and the largest in the country — if completed as planned by the end of the decade.

“It’s very disappointing for the Kentucky craftspeople that I represent,” Holbrook said recently on a video call from his office in Ashland, which was blanketed in ice from a major winter storm. “It’s tough,” he added. “But we are resilient people.”

The news of Century’s decision had barely sunk in for Kentuckians when the company made another surprising announcement.

Last week, Century said it had sold its idled Hawesville smelter in western Kentucky to a data center company, squashing any possibility that the aluminum plant would be restarted. The developer, TeraWulf, will now have access to the site’s 480 megawatts of existing grid capacity for bitcoin mining and high-performance computing — tasks that are less sensitive to power prices than smelting aluminum.

When Century shut down production in Hawesville in 2022, cutting more than 600 jobs, the company pointed to “skyrocketing energy costs” as the primary reason.

Energy has always been the Achilles’ heel of smelters.

The facilities consume tremendous amounts of electricity to transform raw materials into a versatile metal that’s used in cars, planes, power cables, solar panels, and beverage cans. Producers must secure long-term contracts with utilities for affordable, reliable power in order to compete in global markets. But those deals are hard to come by, and smelters that rely on fossil fuel–heavy grids are particularly vulnerable to spikes in coal and gas prices.

For its new smelter, Century had been scouting locations where it could access not only competitive rates but also ample supplies of carbon-free electricity. In 2024, the company was awarded up to $500 million from the Biden administration’s Department of Energy to build a “modern, low-emission” facility as part of a broader federal effort to demonstrate cleaner manufacturing technologies for domestic industries.

It’s unclear whether the terms of Century’s grant have changed under the Trump administration, which is propping up aging coal plants as it works to block renewable-energy projects. But Century recently pointed to Oklahoma’s abundant wind generation and solar power potential in explaining its decision to partner with Emirates Global Aluminium on a smelter near Tulsa.

“Oklahoma is very well located, from a total energy perspective,” Matt Aboud, Century’s senior vice president of strategy and business development, said during a Feb. 2 panel at the S&P Global Aluminum Symposium in Miami.

“Yes, this administration is very much promoting fossil fuels and very much de-emphasizing renewables. But you have to take a 30-to-50-year horizon,” he said. “Ultimately, to really operate a smelter here [in the U.S.], you need an energy strategy that incorporates all the different fuel mixes.”

Aboud didn’t mention Kentucky. But for clean energy advocates, the decision to build in Oklahoma and not the Bluegrass State felt like an indictment of Kentucky’s power system. Coal-fired power plants supplied 67% of the state’s electricity generation in 2024, and gas plants generated another 26%. Hydroelectric dams provided most of the rest, though dozens of solar projects are in development, including ones atop old mining sites.

“Kentucky needs to learn from this and understand that our infrastructure, too, is an economic development tool,” said Elisa Owen, a Louisville-based senior energy organizer with the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign. “We cannot remain invested in 19th-century energy if we want to attract 21st-century business. It’s just as simple as that.”

She said her focus now is ensuring that Century’s last smelter in the state, Sebree, continues operating for years to come. That means pressuring state officials and legislators to usher more renewables onto the grid. “If we understand that Century needs clean energy to be viable in the United States, then that is a story we can tell in Kentucky,” she said. “The Oklahoma smelter snafu needs to be a wake-up call.”

Gov. Beshear, a Democrat, stressed the need to diversify Kentucky’s energy mix in response to Century’s Oklahoma pivot. But GOP state legislators in recent years have adopted measures — Senate Bills 4 and 349 — that are designed to prolong the life of fossil-fueled power plants and make it harder to build renewable energy projects in their place. Opponents of the rules, including investor-owned utilities and manufacturing groups, have warned that the restrictions will jeopardize grid reliability and increase energy costs.

The Kentucky Resources Council and a coalition of other nonprofit groups commissioned an independent study to examine the lawmakers’ claims that relying on fossil fuels is the only way to ensure an affordable, reliable grid. The analysis, by Current Energy Group, found that Kentucky is presently pursuing a high-cost, high-risk path by keeping uneconomic coal plants running and hamstringing efforts to pursue alternatives.

Researchers identified the “least-cost” strategy as one that involves building renewable energy capacity, deploying energy storage, and adding demand-side resources like energy-efficiency programs and rooftop solar to reduce pressure on the utility grid. Using these cleaner resources to replace coal-fired power could save Kentucky customers $2.6 billion by 2050, according to the report, published in December.

This approach is also considered the lowest risk, given that a costly, dirty grid threatens to push out more industries, and since it leaves utilities vulnerable should the state or country ever decide to penalize carbon-dioxide emissions, said Byron Gary, an attorney at the Kentucky Resources Council who helped spearhead the report.

He said that the analysis didn’t include Century’s new smelter when modeling the state’s future power demand. But it did assume that some of the data centers proposed for Kentucky will get built, further increasing the need for carbon-free, lower-cost electricity resources — “which Kentucky clearly doesn’t have right now,” Gary said.

Pro-coal policymakers have framed the AI boom as a godsend for Kentucky’s long-suffering mining industry, as the massive facilities will need lots of around-the-clock power. For now, though, the biggest winner seems to be fossil gas. Last fall, state lawmakers gave Kentucky’s largest utility approval to spend $3 billion on building 1.3 gigawatts’ worth of new gas power capacity to serve future hyperscalers.

Still, that power likely won’t be online anytime soon, given order backlogs: Just getting the turbines needed for new gas plants can take three to five years. By contrast, large-scale solar and wind projects represent the lowest-cost and fastest path to add power to the grid, experts say.

Many residents are pushing back against data centers over concerns of how the megaprojects will affect farmland and raise living costs and electricity prices. For environmentalists who were hoping for a new green smelter, or who were surprised by Hawesville’s rebirth as a server farm, the tech infrastructure is little consolation.

Lane Boldman, executive director of the Kentucky Conservation Committee, said she doesn’t think that data centers will revitalize the state’s hard-hit industrial and mining communities in the same way that the Department of Energy had initially intended when awarding Century’s $500 million smelter grant.

“What the Biden administration had been trying to do with a lot of these grants was not just to provide economic development or drive cleaner technology but also to do something to restore communities that had been working in the energy sector before, so that they’re not abandoned,” she said.

“You want to be able to bring the communities along in that transition,” she added. “And what they will now get instead is either nothing or a data center, and that just wasn’t the plan.”

Holbrook, for his part, said he welcomes the potential influx of data centers in Kentucky and the regions of Ohio and West Virginia that his tristate labor council represents. As he sees it, the multibillion-dollar developments could provide well-paying construction jobs for the next decade and beyond as tech companies expand their footprints.

“We’re trying to embrace it, and we want to be at the table and building these campuses,” he said. “You kind of have to dance with the person that brought you. So that’s how we are with this situation.”

Last Friday, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright held a press conference to talk about how the power grid didn’t collapse during late January’s Winter Storm Fern.

Some of the things he said were true. Others weren’t. It’s important to know the difference — especially as the Trump administration routinely uses misleading statements to justify decisions that make the power system dirtier, more expensive, and ultimately less reliable.

Wright, a former fossil gas–industry executive who has overseen the administration’s hard turn against clean energy, praised the efforts of utility workers who rallied from across the country and worked around the clock to restore power to more than 1 million people after ice and falling trees took out grid lines. That’s true, and good.

But the centerpiece of Wright’s nearly hourlong presentation was a series of charts, propped up on an easel, that served as a launchpad for the same kind of half-truths and obfuscations that have typified his approach to the job.

His pie charts showed the mix of electricity generation at the peak of wintertime demand across the eastern U.S. and in New England. There was a lot of fossil gas, a big slice of coal and of nuclear, and, in New England, a lot of oil — a key source of emergency generation in wintertime. Meanwhile, wind and solar power, the resources Wright called the “darlings” of the climate movement, were represented by very small slices.

In Wright’s view, these charts tell a story of waste and excess. People had to pay for the construction of all that renewable energy, and the poles and wires required to carry it, only for that power to disappear when the grid needed it most.

Here’s how he put it: “If you can add reliable power at peak demand time, you’re additive to the grid. If you can’t, you’re just … a cost center. You’re not actually helpful for the grid.”

This is a gross oversimplification of the complex ways that different types of power add value to the grid. As Wright well knows, people don’t need electricity on just the hottest or coldest days. They need it every day, all 8,760 hours of the year. And how that power is generated on a daily basis matters just as much as how it gets produced in extreme circumstances — for people’s wallets, their health, and the planet.

The vast majority of the time, wind and solar — and energy storage — reliably provide electricity to the grid. During the first 10 months of 2025, the U.S. got nearly one-fifth of its electricity from these sources.

Why is that? Because the electricity that renewables provide is cheap and plentiful. Nowadays, it is often less expensive than gas-fired power. And renewables are certainly much cheaper than coal power, even as Wright’s Department of Energy has spent the last year propping up the dirty fossil fuel at great cost to consumers.

For the past two years, solar, wind, and storage have made up more than 90% of the new electricity capacity being added in the U.S. — and around the world. And we will need to keep up that pace for the U.S. to meet growing power demand from data centers and electrification without causing already rising electricity costs to soar further.

But Wright casts cheap, clean power as mere empty calories that steal market share from coal, gas, and nuclear power. Energy supplied only when “the weather is mild, when the sun shines or the wind blows, doesn’t add anything to the capacity of our electricity grid,” he said. “It just means we send subsidy checks to those generators, and we tell the other generators, ‘Turn down.’”

Here, Wright mischaracterizes how utilities and grid operators dispatch power plants. Wind and solar often “turn down” when they’re generating more power than the grid needs. But fossil-fueled power plants stop generating when their power is too expensive to compete with what wind and solar generators are offering — market forces in action.

It’s worth mentioning, too, that utilities and grid operators are well aware that wind and solar are weather-dependent and don’t produce all the time. These experts constantly assess the availability of all resources — not just renewables — and plan accordingly.

Wright also neglected to say that fossil fuels themselves can fail during winter storms — and often in less predictable and more harmful ways than when the sun sets or the wind dies down.

That’s what happened during Winter Storm Uri in 2021. That storm swept over the U.S. Southeast — and in particular, Texas — bringing subzero temperatures that froze wellheads and restricted the flow of gas to power plants, which were experiencing their own weather-related failures. The result was catastrophic: More than 200 people died and roughly 4.5 million homes and businesses lost power. Similar gas-system freeze-ups drove winter blackouts across the Southeast in 2022 and during the 2014 “polar vortex” in the Northeast.

During Winter Storm Fern, it was a different story: Generator failures did not force utilities and grid operators to shut off power. One likely reason is that, in the years since Uri, regulators have imposed winterization requirements on owners of gas power plants in Texas and other parts of the country, though just how effective those interventions were is not yet clear.

Another probable factor contributing to the grid’s resilience this time around was having a better overall mix of resources. Energy experts agree that portfolios of mutually reinforcing resources are the key to grid reliability. In the Lone Star State, solar and battery storage have surged in recent years. Texas’ grid weathered this January’s cold snap, experts say, because it had an array of fuel sources on hand.

But of course, Wright didn’t acknowledge any of that. He simply railed against renewables, painting them as leeches on the power system.

Fossil-fueled power plants remain vital to the U.S. grid, whether they’re designed to run around the clock or only during emergencies, as is the case for New England’s oil-burning generators — one of the grid’s costliest resources, precisely because they run so infrequently. But renewables are vital, too. In New England, the gigawatts of offshore wind being built from Connecticut to Maine that have been under attack since the first day of the second Trump administration are also one of the most valuable winter resources for the region.

The DOE’s job is not to take a snapshot of the worst 15 minutes of the year and use it to justify policies that freeze in place that exact mix of grid resources. Instead, it’s to assess and manage the grid’s evolving technical, economic, environmental, and climatic realities, and to foster newer, better resources to replace those that aren’t keeping up.

The more Wright pretends otherwise, and uses half-truths to force fossil fuels onto a system that would be better served by cheaper and cleaner alternatives, the worse off we’ll all be.

It’s a tough time for U.S. companies trying to make a go of green hydrogen.

The Trump administration is threatening to cut billions of dollars in funding for hydrogen hubs and rapidly phasing out key tax incentives for the fuel. Major projects are getting canceled. Companies banking on the sector are struggling. And the wholesale abandonment of U.S. climate policy has undermined confidence in market prospects for low-carbon hydrogen that were already shaky before President Donald Trump won a second term.

Even so, Raffi Garabedian, CEO of U.S.-based electrolyzer manufacturer Electric Hydrogen, sees a path forward for his firm — and the industry as a whole.

It won’t be nearly as smooth or as fast as he had hoped. And much of it will take place in Europe, where climate policy and fossil fuel costs make green hydrogen more viable. But even in the U.S., there are still some promising prospects for projects that can get built quickly enough, capture ever-cheaper renewable energy, and find motivated buyers, he said.

Take Project Roadrunner, which is being built in West Texas by alternative-fuels startup Infinium to produce “e-fuels” — drop-in replacements for jet fuel and other fossil fuels made by combining low-carbon hydrogen with waste carbon captured from industrial emissions. Infinium plans to start commercial production at the site in 2027. Last May, Infinium selected Electric Hydrogen’s 100-megawatt HYPRPlant electrolyzer system, which uses water and electricity to make the hydrogen.

Infinium is contracting for clean electricity for the site, including 150 megawatts of wind power from NextEra Energy. It has also won long-term offtake commitments from American Airlines, Citibank, and International Airlines Group to pay for Project Roadrunner’s sustainable aviation fuels made with renewable electricity — “eSAF” in industry jargon. That’s a vital step for securing the stable financing required to build first-of-a-kind facilities, particularly in the nascent green-hydrogen field.

To wit, Brookfield Asset Management and Breakthrough Energy Catalyst are providing funding.

“We’re superexcited about eSAF in particular, because there’s strong policy support. And even at the voluntary level, there seems to be strong corporate willingness to pay for air-travel decarbonization,” Garabedian said.

Other orders have followed for his firm. In September, HIF Global announced it will use Electric Hydrogen’s electrolyzers for a plant in Texas that will produce e-fuels. And in December, Synergen Green Energy said it would install two 120-megawatt HYPRPlants for a green ammonia plant it’s developing on the Texas Gulf Coast.

The HIF Global and Synergen projects are in the early stages of development, and seeing them through will depend on securing financing, permits, and buyers for their e-fuels. In today’s post-boom green-hydrogen market, that’s far from a sure thing.

But in Texas, several factors work in their favor. The Gulf Coast has the infrastructure, from its oil and gas industries, to make, store, and transport hydrogen at large scale. It has access to large and growing amounts of solar and wind power to supply electrolyzers that need affordable clean electricity to compete with fossil fuels.

Another key factor in driving down green-hydrogen costs is making cheaper electrolyzers and supporting equipment. And on that front, Electric Hydrogen is relying on proving out its lower-cost claims to win advantage.

The company, which has raised over $600 million, has built a factory in Devens, Massachusetts, to make its electrolyzer stacks — the core parts of the proton exchange membrane (PEM) systems that use electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. It has also partnered with other component manufacturers and engineering firms to streamline and standardize building the many other working parts of a green hydrogen plant — including power conversion, gas processing, water treatment, and thermal management — in a more modular way, Garabedian said.

Overall, Electric Hydrogen claims its total installed costs are less than half those of systems using electrolyzers from PEM competitors such as Germany’s Siemens Energy and Thyssenkrupp Nucera, as well as those of lower-cost alkaline electrolysis systems built by Chinese companies, which make up the majority of installed capacity today.

“The most important thing in our business is cost,” Garabedian said, but “it doesn’t matter what your electrolyzer costs — it’s what your total installed plant costs.”

However, cost comparisons between different electrolyzer manufacturers and fully built green-hydrogen facilities are far from an exact science in this industry, said Pavel Molchanov, an energy analyst at Raymond James.

The world had approximately 2 gigawatts of hydrogen electrolyzers in operation at the end of 2024, according to the International Energy Agency’s “Global 2025 Hydrogen Review.” That amount, Molchanov said, is “a rounding error” compared with global fossil fuel–based hydrogen capacity.

Electrolyzer companies face a tough market, Molchanov added. The International Energy Agency reports that global electrolyzer manufacturing capacity expanded from just over 10 gigawatts in 2022 to more than 50 gigawatts in 2025. But in that time, forecasted demand for green hydrogen has plummeted, which leaves “far more manufacturing capacity available than what’s getting deployed,” Molchanov said. “That’s a lot of underutilized factories.”

That imbalance between electrolyzer supply and demand has taken its toll. Last week, major U.S. engine and generator manufacturer Cummins announced it was halting commercial efforts for its electrolyzer business, which constitutes about 1 gigawatt of manufacturing capacity in the U.S. and Spain. Demand for electrolyzers has “dried up,” Chief Financial Officer Mark Smith said in a November earnings call.

Garabedian conceded that challenge: “We definitely built the company for growth, and we’ve seen growth slower than we anticipated and hoped. As I look at the market, I think we’re looking at another year and a half of muted activity.”

But he also stressed that buyers for green hydrogen and products made from it aren’t likely to be found in the U.S., at least not in the near term. Neither the politics under Trump nor the economics are in its favor.

The country’s cheap and abundant supply of fossil gas means that green hydrogen remains roughly three times more expensive than “gray hydrogen,” which is derived from fossil gas. This is true even for projects that secure the 45V hydrogen tax credits, which expire at the end of next year.

“No one in the U.S. is thinking about deep decarbonization these days,” Garabedian said. “And the price of natural gas is such in the U.S. that it’s hard to impossible for green hydrogen to compete head-to-head economically.”

In Europe, by contrast, gas prices are regularly three to four times as high as they are in the U.S., making green hydrogen more cost competitive, Molchanov noted. And policies set by the European Union and adopted by national governments require major industries to meet carbon-cutting targets, which are expected to spur demand for clean hydrogen.

That’s why the HIF Global and Synergen projects that Electric Hydrogen is supplying electrolyzers to in the U.S. are aimed at exporting their products, primarily to Europe, Garabedian said.

It also explains Electric Hydrogen’s push into Europe for its next wave of electrolyzer deals. In 2024, Germany-based energy company Uniper picked Electric Hydrogen for a 200-megawatt green hydrogen and ammonia plant, set to start production in 2028. Garabedian said the company will soon announce a similarly scaled German project, though he declined to provide more details.

“It is a complicated global market. And we, as an American supplier, have a strategy to address that,” he said. “Unfortunately, it does mean moving a lot of our supply chain to Europe for European suppliers.”

When music superstar Bad Bunny climbed an electric pole during the Super Bowl halftime show on Sunday, he showcased a painful reality during what was otherwise a joyous celebration of Puerto Rican culture.

Puerto Rico’s power grid has been crumbling for nearly a decade, ever since Hurricanes Irma and Maria battered the U.S. territory in 2017 and all but destroyed its centralized electricity system. Bad Bunny highlights the ailing grid in his 2022 song “El Apagón” (“The Blackout”), which he sang yesterday from a sparking utility pole in a show seen by perhaps 135 million viewers.

Despite billions of federal recovery dollars and post-hurricane repairs, Puerto Rico’s 3.2 million residents continue to endure widespread disruptions, electrical surges, and soaring electricity rates — even on storm-free days. Utility customers in Puerto Rico experienced an average of 27 hours of power grid interruptions not related to major events like hurricanes per year between 2021 and 2024. By contrast, people living on the U.S. mainland lacked power for an average of just two hours per year, according to federal data.

Yet rather than invest in Puerto Rico’s recovery, the Trump administration is clawing back key federal funding meant to modernize and decarbonize the territory’s electricity system.

In January, the Department of Energy canceled $450 million for grid resilience programs in Puerto Rico, Latitude Media recently reported. The clawback effectively marks the end of the $1 billion Puerto Rico Energy Resilience Fund that the Biden administration launched in 2023 to help keep people’s lights on and their schools open, hospitals running, and supermarkets stocked.

President Donald Trump’s DOE had previously redirected $365 million of that funding meant for rooftop solar and battery storage projects toward “practical fixes and emergency activities.” To the administration, that means doubling down on the old model: far-flung power plants fueled by coal, oil, and gas, which send electricity along transmission lines that crisscross the island — and which were mercilessly mowed down during last decade’s hurricanes.

But some energy experts and community leaders say that approach is impractical. They argue that building clean and distributed energy systems close to population centers is the best way to supply Puerto Ricans with reliable, affordable power that can withstand natural disasters.

Rooftop solar systems with batteries have already become a lifeline for residents and community groups across the archipelago. Amid a power-generation shortfall last July, Puerto Rico’s grid operator relied on customers’ batteries to prevent the grid from collapsing.

As of June 2025, 1.2 gigawatts of grid-connected rooftop solar were installed on homes and businesses, supplying more than 10% of the total energy used, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. That tally doesn’t include the many off-grid systems that people have installed to shore up their own resiliency.

Still, many low- and moderate-income households aren’t able to access the benefits of clean, distributed energy, a challenge that the federal programs were meant to help address. Advocates are still pressing ahead. Casa Pueblo, a community organization in Puerto Rico, recently released a study that outlines how more people can be brought into the fold with “microgrids” — groups of solar panels and batteries that serve entire districts or neighborhoods, not just individual buildings.

In 2023, Casa Pueblo launched one of Puerto Rico’s first microgrids in the tranquil mountain town of Adjuntas. The initiative has since expanded to include five small systems in Adjuntas that serve a handful of residences and 15 businesses, including La Conquista Laundry. Nicky Vázquez, who owns the laundromat, said he’s seen an 80% reduction in his electricity bill and had no power outages since joining the microgrid in mid-2025.

“Now I have stability, I don’t run out of power, and I can continue to provide service,” Vázquez said in a statement provided by Casa Pueblo.

Yesterday’s Super Bowl was hardly the first time that Bad Bunny, whose real name is Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, has spoken out about Puerto Rico’s power struggles. Last April, when the territory was once again plunged into darkness, he asked on social media: “¿Cuando vamos a hacer algo?” When are we going to do something?

Technological advances are expanding where geothermal electricity canbe produced - making it a cost-competitive, secure alternative to gas forindustry and other power-intensive users.

This analysis examines how advances in geothermal technology are changingthe prospects for geothermal electricity in Europe: its resource potential, costsand deployment trends. The report considers how policy conditions shape thepace of new projects and geothermal’s role in evolving electricity systems.

Modern geothermal is pushing the energy transition to new depths, opening up clean power resources that were long considered out of reach and too expensive. But today, geothermal electricity can be cheaper than gas. It’s also cleaner and reduces Europe’s reliance on fossil imports. The challenge for Europe is no longer whether the resource exists, but whether technological progress is matched by policies that enable scale and reduce early-stage risk.

Tatiana Mindekova

Policy Advisor, Ember

The EU’s Geothermal Action Plan must include clear commitments to liberate Europe’s power sector from costly fossil fuel dependency. The potential to replace 42% of coal and gas generation with geothermal is simply too significant to ignore. Ember’s report highlights the crucial role geothermal plays in delivering affordable energy, security, and competitiveness. With Energy Ministers and the European Parliament calling for concrete action, it is now up to the European Commission to remove the barriers to mass geothermal deployment.

Sanjeev Kumar

Policy Director, European Geothermal Energy Council

Europe has far more geothermal potential than is commonly accounted for. Next-generation geothermal strengthens Europe’s heat sector and extends its impact to clean, secure, and reliable electricity across much of the continent. Continued investment in innovation and supportive policy can turn this resource into a major pillar of EU’s clean firm power system.

Jenna Hill

Superhot Rock Geothermal Innovation Manager, Clean Air Task Force

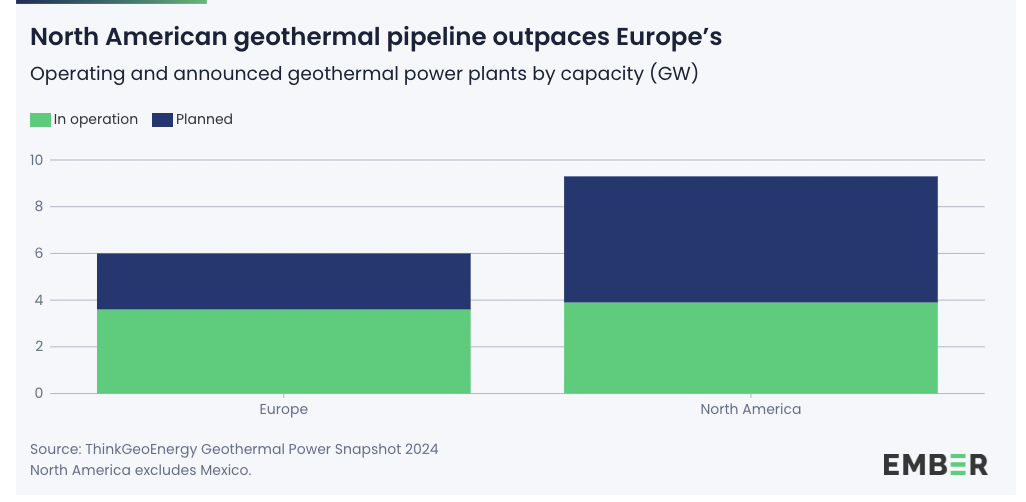

Technologies allow geothermal to deliver scalable and clean power across much of Europe. Not just in volcanic regions. Across the European Union, around 43 GW of enhanced geothermal capacity could be developed at costs below 100 €/MWh, placing geothermal firmly within reach as a competitive source of firm, low-carbon electricity. Yet much of this technological progress has gone largely unnoticed and geothermal is still widely viewed as unavailable across much of Europe.

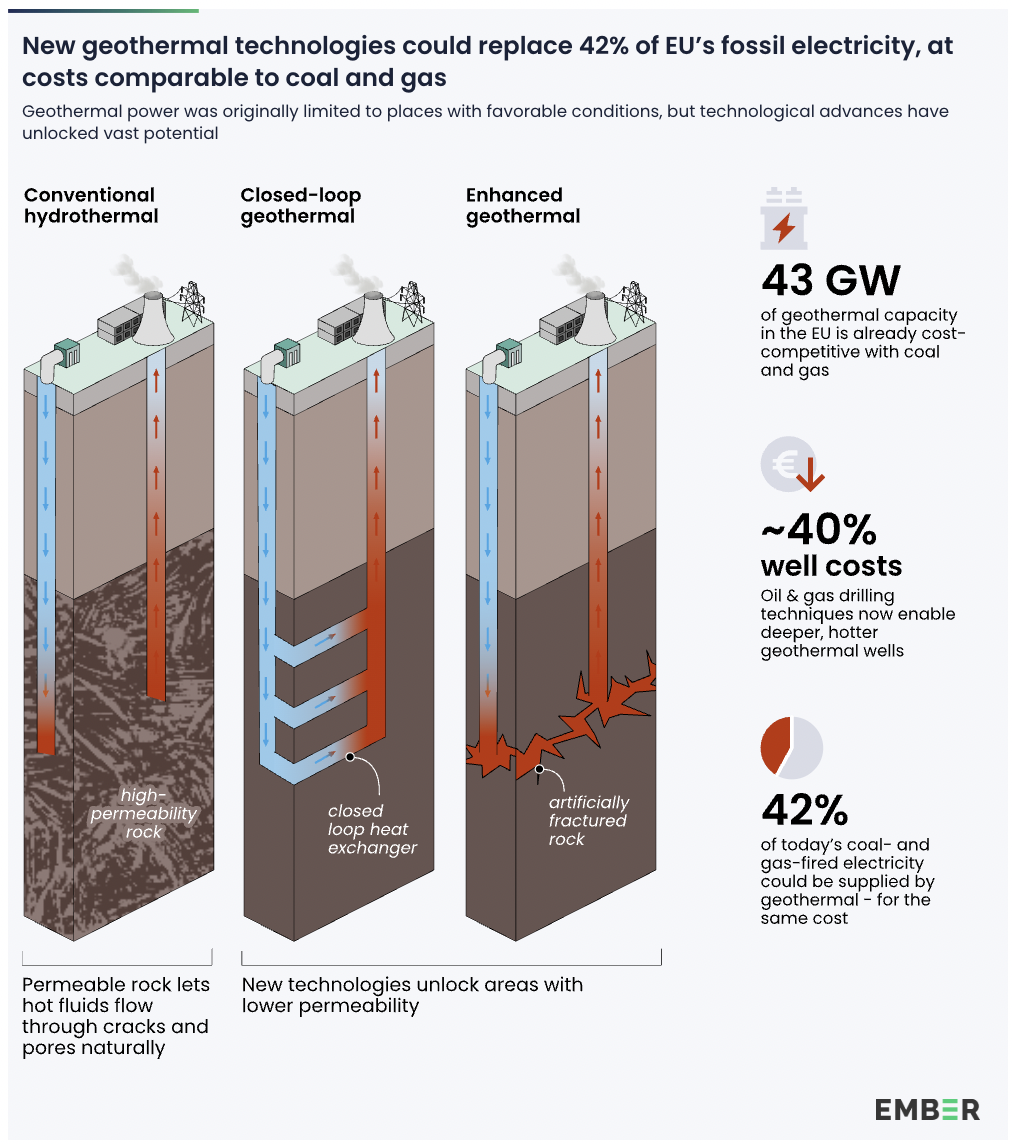

Geothermal power generation was long considered viable only in volcanic regions such as Iceland or Indonesia. Conventional geothermal relied on underground rock formations that were both hot and naturally permeable, allowing water already present at depth to circulate and transport heat. These rare conditions confined large-scale deployment to a limited number of regions worldwide. As a result, geothermal energy remained a niche contributor to global electricity generation (99TWh or less than 0,5% in 2024) despite its dispatchable nature and low emissions profile.

During the last decade, progress in geothermal technologies – often referred to as ‘next generation geothermal’ – has removed the need for naturally occurring permeability, meaning the presence of open pores in rock that allow fluids to flow. New approaches can now create or enhance these flow pathways artificially. Combined with more cost-effective deep drilling and advances in power-conversion systems that enable electricity generation at lower temperatures, significantly expanding the range of geological settings suitable for geothermal power generation. As a result, geothermal deployment is expected to accelerate rapidly: by 2030, nearly 1.5 GW of new capacity is expected to come online each year globally, three times the level added in 2024. At the global level, geothermal could meet up to 15% of the growth in electricity demand by 2050.

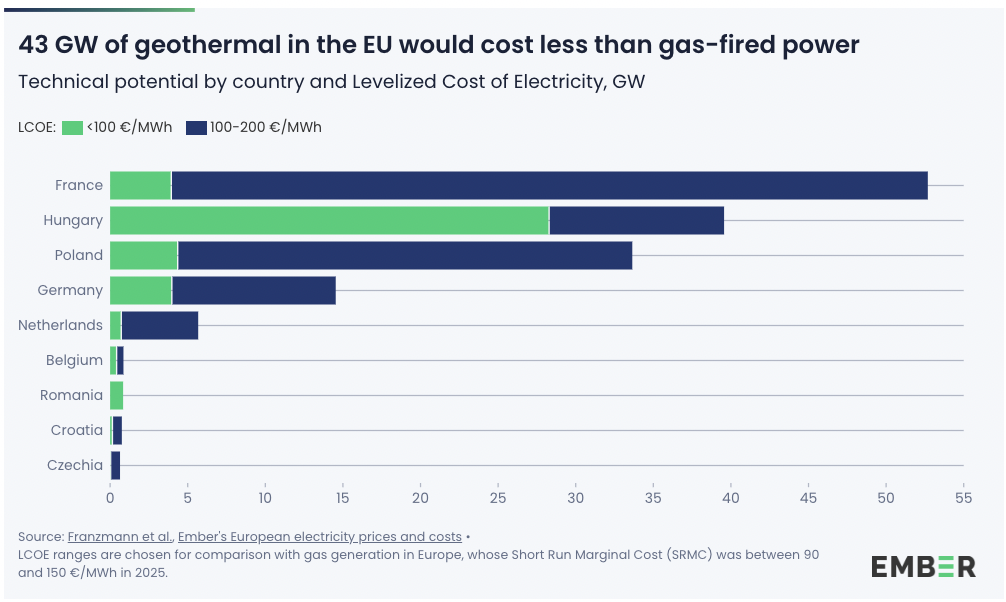

Recent advances in geothermal systems mean that geothermal electricity can now be produced at prices comparable to coal- and gas-fired generation, even outside traditionally high-temperature zones. Focusing on projects with estimated costs below 100 €/MWh – consistent with prices (short-run marginal costs) set by coal- and gas-fired generation in European power markets – and accounting for reservoir behaviour, plant performance and drilling depth, the techno-economic potential for geothermal power in continental Europe reaches around 50 GW.

Under this threshold, Hungary accounts for the largest share, with around 28 GW, followed by Türkiye with almost 6 GW and Poland, Germany, and France with around 4 GW each.

For EU member states alone, this corresponds to around 43 GW of deployable geothermal capacity, capable of generating approximately 301.3 TWh of electricity per year given geothermal’s high capacity factor. This is equivalent to around 42% of all coal- and gas-fired electricity generation in the EU in 2025.

At these cost levels, geothermal power would be competitive with the prices set by coal- and gas-fired generation in European power markets, where short-run marginal cost has been oscillating between 90 and 150 €/MWh in 2025. Not only can geothermal power capacity be developed at low prices, but as a technology with no fuel costs, it brings the additional benefit of being insulated from fuel price volatility and exposure to rising carbon costs, strengthening its role as a stable source of firm, low-carbon electricity over time.

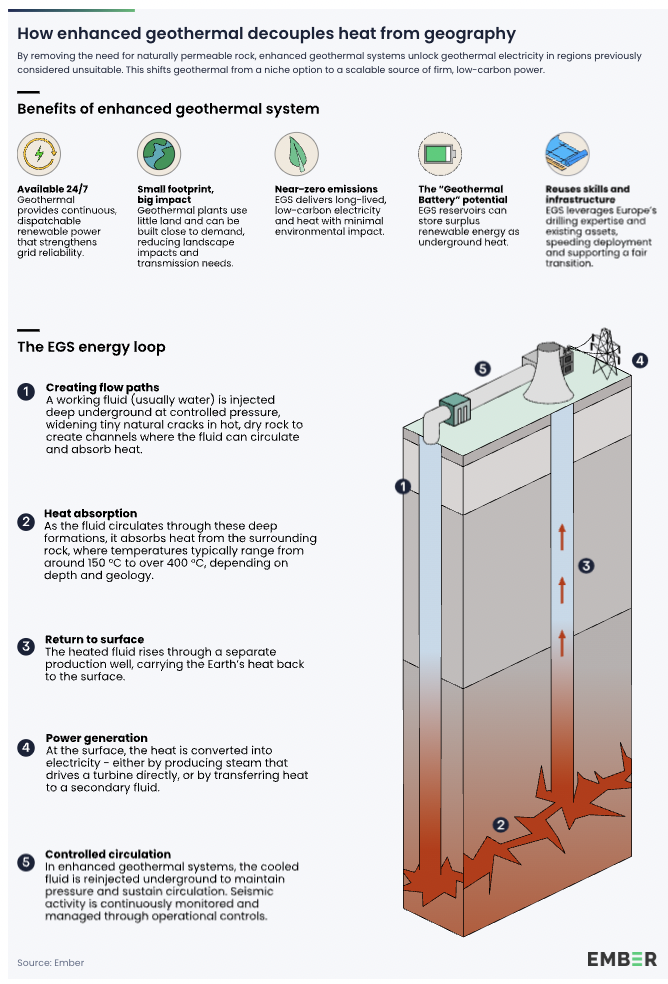

The potential of geothermal energy for electricity generation is expanded by changes in the design of geothermal projects. The term next-generation geothermal encompasses several design improvements to geothermal systems. These include accessing underground heat without relying on natural heat pathways, using artificial heat carriers, or creating closed-loop systems. A type of next generation technology most commonly deployed is Enhanced Geothermal System(s) (EGS). EGS can engineer reservoirs in deep, hot rock where natural water or permeability is low or absent, unlocking potential beyond traditional hotspots.

In EGS projects, wells are drilled into hot rock and permeability is created or enhanced to allow a working fluid to circulate and extract heat. The heated fluid is brought to the surface through these artificial cracks to generate electricity. Experience from recent projects shows that seismic risks resulting from such drilling can be managed through monitoring and operational controls.

Geothermal reservoirs can be operated flexibly to absorb surplus wind or solar electricity indirectly, primarily through increased pumping and injection, and later the release of stored thermal and pressure energy to generate additional power. By varying injection and production rates, operators can “charge” the reservoir and later “discharge” it to increase output during high-value periods. Simulations show that heat can be stored for several days with efficiencies comparable to lithium-ion batteries. Because this capability is built into the same infrastructure used for power generation, it adds flexibility at low additional cost.

In addition, geothermal operations can generate value beyond electricity through the recovery of critical minerals from produced brines. Lithium concentrations in geothermal brines typically range in levels that can be commercially viable using new direct lithium extraction techniques. These methods recover up to 95 % of the lithium contained in the brine, compared with roughly 60 % from hard-rock mining, while using far less water and generating almost no carbon emissions.

Geothermal electricity is already cost-competitive with fossil fuels in Europe. The levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) of geothermal power – the cost of producing one unit of electricity based on the construction and operating costs of a power plant over its lifetime – is already low, at around USD 60 /MWh, placing it below most fossil-fuel generation (~ USD 100 / MWh in Europe). This reflects geothermal’s high capacity factors and the fact that existing projects have largely been developed in favourable geological conditions using conventional designs, with average depth of well between 1 to 3km.

Drilling and reservoir development remain the dominant drivers of capital expenditure, making early-stage investment risk a central barrier for deeper and more complex projects. Over the past decade, however, drilling and reservoir-engineering techniques adapted from the oil and gas sector have reduced well costs by roughly 40%, enabling economically viable access to hotter and deeper resources. As these capabilities scale, they expand the share of geothermal resources that can be developed at competitive cost.

Geothermal electricity potential increases as drilling reaches deeper, higher-temperature resources, but the depth at which suitable temperatures occur varies significantly across countries. In the European Union, assessments limited to resources accessible at depths of up to 2,000 m — where sufficiently high temperatures are available only in a subset of locations — yield a relatively constrained level of technical potential (139GW). As access extends to deeper and hotter resources, geothermal conditions become more widely available across the EU. Extending the depth range to 5,000 m increases the estimated potential by more than 50 times, while access to resources down to 7,000 m results in an increase of roughly 180 times.

In the EU, projects that take advantage of the newly accessible resources are already under construction, reaching depths beyond 4000m. Moreover, there are existing projects that have already reached depths close to 5000m, demonstrating that utilising geothermal resources at these depths commercially is already achievable with today’s technology.

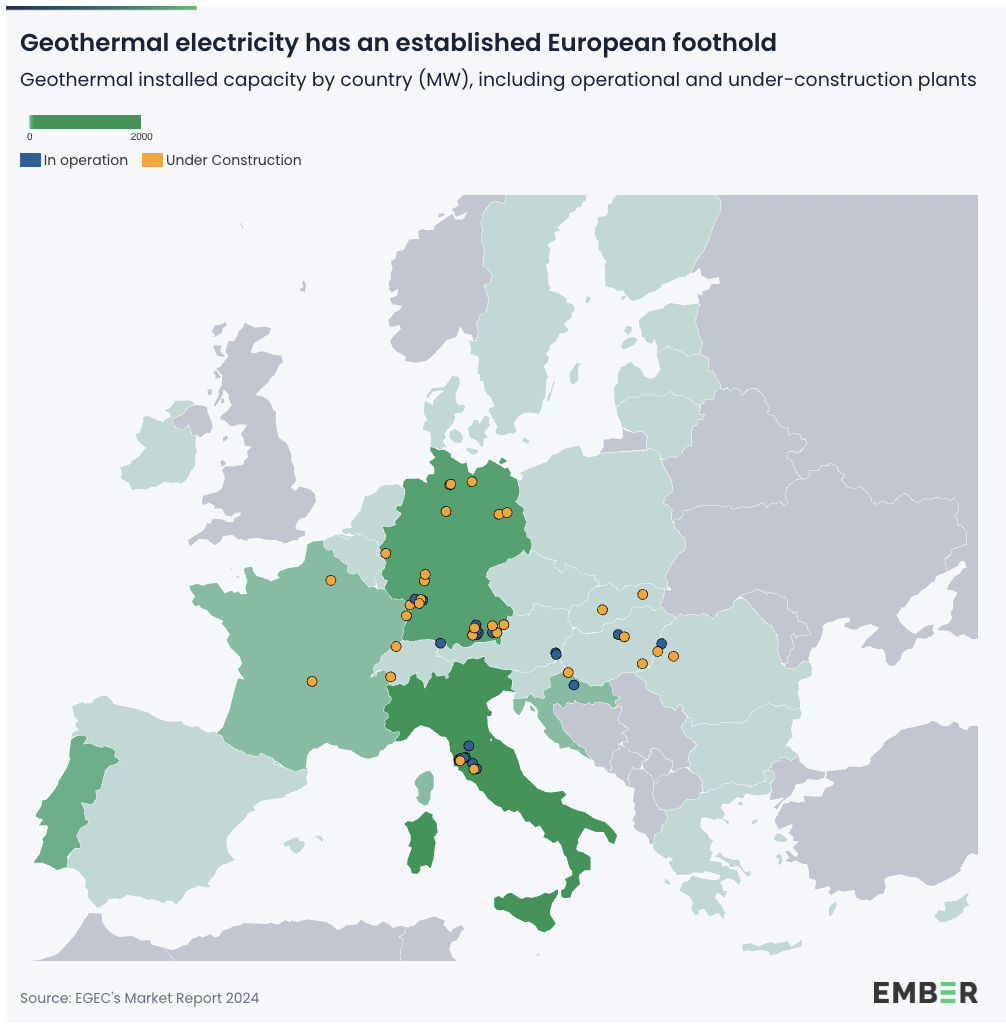

Europe played a central role in the development of geothermal energy. The world’s first geothermal electricity was produced in Italy, in 1904, and as of 2024, Europe had 147 geothermal power plants in operation. Of these, 21 have been producing electricity for more than 25 years, underscoring the long-term value of geothermal investments. In 2024, these plants produced around 20 TWh of electricity from just over 3.5 GW of installed capacity (roughly one-fifth of global geothermal capacity).

Geothermal generation in Europe remains highly concentrated. The majority of its output came from Türkiye, Italy and Iceland, which together accounted for nearly all geothermal generation in the region. Beyond these established markets, activity is spreading: several countries already produce geothermal electricity, including Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Austria and Portugal, while new capacity is under development in Belgium, Slovakia and Greece. Across Europe, around 50 geothermal power plants are currently moving through development, from early exploration to grid connection, with Germany leading in active projects.

Pilot EGS projects launched in France, Germany and Switzerland in the 2000s demonstrated that hot, impermeable rock could be converted into productive reservoirs. More than 100 EGS projects have now been carried out worldwide, with Europe accounting for the largest share (42), followed by the United States (33), Asia (15), and Oceania (12). More recently, EGS projects have moved from commercial demonstration to full scale development. Advanced geothermal systems are also progressing, with Europe’s first closed-loop project now operating as a grid-connected power plant in Germany.

Despite this progress, Europe is at risk of losing ground. Lengthy permitting processes, inconsistent national support and the absence of a coordinated EU strategy and accompanying policies have slowed commercial deployment. In contrast, projects in the United States and Canada are now scaling up many of the methods first tested in Europe, supported by targeted policy incentives and private investment. Delayed deployment also risks shifting learning effects, supply-chain development and cost reductions to other regions, increasing future costs for European projects even where resources are available. Without a stronger focus on market-scale financing, Europe may miss the economic and industrial benefits of technologies it helped pioneer.

Geothermal power plants could play a crucial role in meeting the fast-growing electricity demand of data centres, whose global consumption could more than double by the early 2030s. As data-centre capacity expands, geothermal offers a stable, always-available source of electricity that can be developed alongside these sites. Its continuous output helps balance the wider power system and reliably serves data centres energy-intensive operations over the long term.

Recent research by Project InnerSpace shows that if current clustering trends continue, geothermal could economically meet up to 64 percent of new data centre demand in the US by the early 2030s and even more when developments are located near optimal resources.

At the same time, AI is reshaping geothermal development. By analysing seismic and geological data, it helps identify promising sites, streamline drilling and improve performance – creating a feedback loop in which each technology accelerates the other.

Major technology companies are no longer experimenting with geothermal – they are deploying it. Announced in 2021 and now fully operational, Google’s partnership with Fevro marked the world’s first enhanced geothermal project built for a data centre. Others are following suit, with Meta signing a 150-megawatt deal with Sage Geosystems in the United States. In Europe, no similar cooperations were announced.

In the United States, geothermal power is now firmly within the clean-energy toolkit. Federal legislation such as the Inflation Reduction Act has expanded investment and production tax credits to include geothermal electricity, establishing clearer economic signals for developers. Meanwhile, geothermal enjoys bipartisan backing because it leverages drilling and subsurface expertise tied to familiar industries and offers around-the-clock output.

In Europe, several Member States, including Austria, Croatia, France, Hungary, Ireland, and Poland, have developed national geothermal road maps aimed at supporting subsurface investment, demonstration wells and domestic supply chains, in some cases backed by dedicated financing and targets.

Only more recently has momentum begun to build at the EU level. In 2024, both the EU Council and the Parliament voiced their support for accelerating geothermal and proposed a European Geothermal Alliance, to be set up by the Commission. As geothermal strongly aligns with the EU’s priorities on competitiveness, energy security and industrial decarbonisation, the forthcoming European Geothermal Action Plan is a much-needed and timely development.

However, translating strategic recognition into deployment will depend on how geothermal is integrated across broader EU policy instruments. As preparations for the next Multiannual Financial Framework advance, and initiatives such as the Industrial Decarbonisation Accelerator Act aim to strengthen permitting and demand signals for clean solutions, geothermal’s high upfront risk, long asset lifetimes and system value as a source of firm capacity make coordinated EU action particularly important. In practice, the effectiveness of European geothermal framework will hinge on progress in three areas at EU level:

Download the report here.

Hot stuff: geothermal energy in Europe [PDF]

Techno-economic geothermal capacity potentials for power in the EU are aggregated from data presented in the paper “Global geothermal electricity potentials: A technical, economic, and thermal renewability assessment” by Franzmann et al., whose cost curves are limited to the “Gringarten approach” for reservoir modelling (please refer to the original publication for further details).

Raw geothermal energy surface densities in Europe are computed starting from Global Volumetric Potential (GVP) data from the Geomap tool by Project Innerspace, in particular from the modules with 150 °C cutoff temperature (minimum for power applications) and depths of 2000 m, 5000 m and 7000 m.

GVP data points, reported on a geographical grid with 0.17×0.17 degrees latitude-longitude resolution, are then averaged over the surface of each analysed country to obtain national energy values, expressed in PJ/km2.

The conversion to useful electrical energy is then performed by multiplying each country’s total by exergy efficiency (~30%, based on a 150 °C temperature for hot rock and on a 25 °C temperature for ambient) and utilization (~20%, based on conservative ranges out of the GEOPHIRES v2.0 simulation tool) factors. Capacity equivalents are calculated assuming an 80% load factor and a 25-years lifetime for a modern geothermal power plant. Results from the steps in this paragraph were used to validate the methodology through benchmarking with aggregated values from “The Future of Geothermal Energy” report by IEA.

The extraction of the original GVP data by Project Innerspace was performed in November 2025. Features and availability of modules within the Geomap tool might have changed since then.

Estimates for electricity generation in the EU are based on an 80% load factor, consistent with the rest of the methodology and representative of modern geothermal power plants. While cumulative generation and capacity estimates for 2025 only would yield a load factor of around 65%, future technological (improvements in plant operations) and market (increases in electrification and grid availability) conditions can justify assumptions for utilization of geothermal power capacity at or above this level.

Throughout the report, “Europe” refers to the European Union plus Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom and Western Balkan countries, reflecting the geographical scope of geological resource assessments and existing geothermal deployment. Where analysis refers specifically to the European Union, this is stated explicitly.

The authors would like to thank several Ember colleagues for their valuable contributions and comments, including Elisabeth Cremona, Pawel Czyzak, Reynaldo Dizon, Burcu Unal Kurban, Eli Terry, and others.

We would also like to extend our gratitude to our partners Clean Air Task Force and European Geothermal Energy Council for providing external review as well as valuable data and insights.

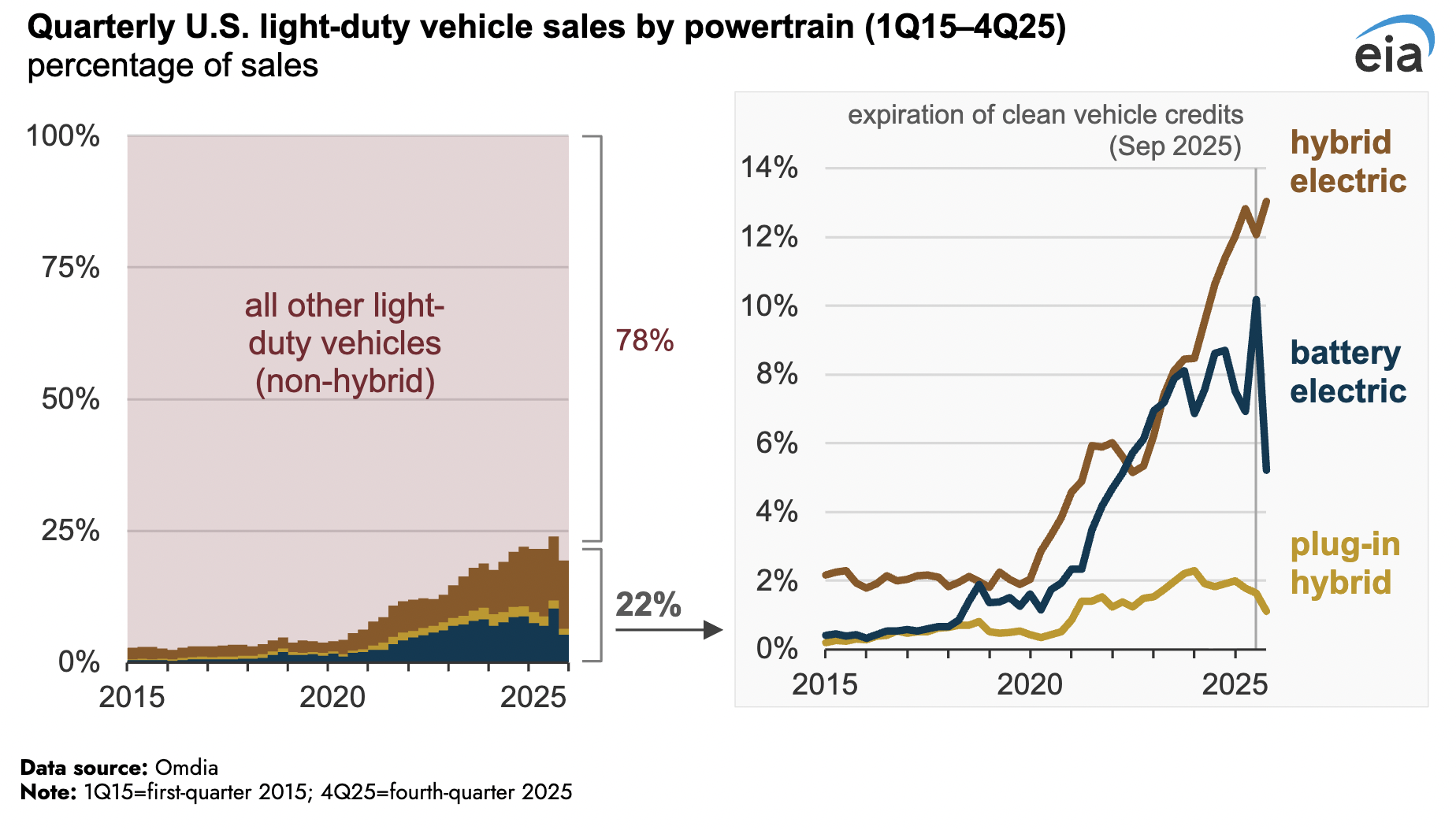

About 22% of light-duty vehicles sold in 2025 in the United States were hybrid, battery electric, or plug-in hybrid vehicles, up from 20% in 2024. Among those categories, hybrid electric vehicles have continued to gain market share while battery electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid vehicles decreased, according to estimates from Omdia. In the second half of 2025, battery electric vehicle sales increased before sharply declining in response to the expiration of tax credits at the end of September.

These different vehicle types affect the broader energy sector in different ways. Battery electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid vehicles can consume electricity from isolated power sources or, more commonly, from the grid. So, their use can affect electricity demand. By comparison, hybrid electric vehicles do not have plugs, so they don’t directly affect grid-delivered electricity demand and were not eligible for any of the federal tax credits that expired in September.

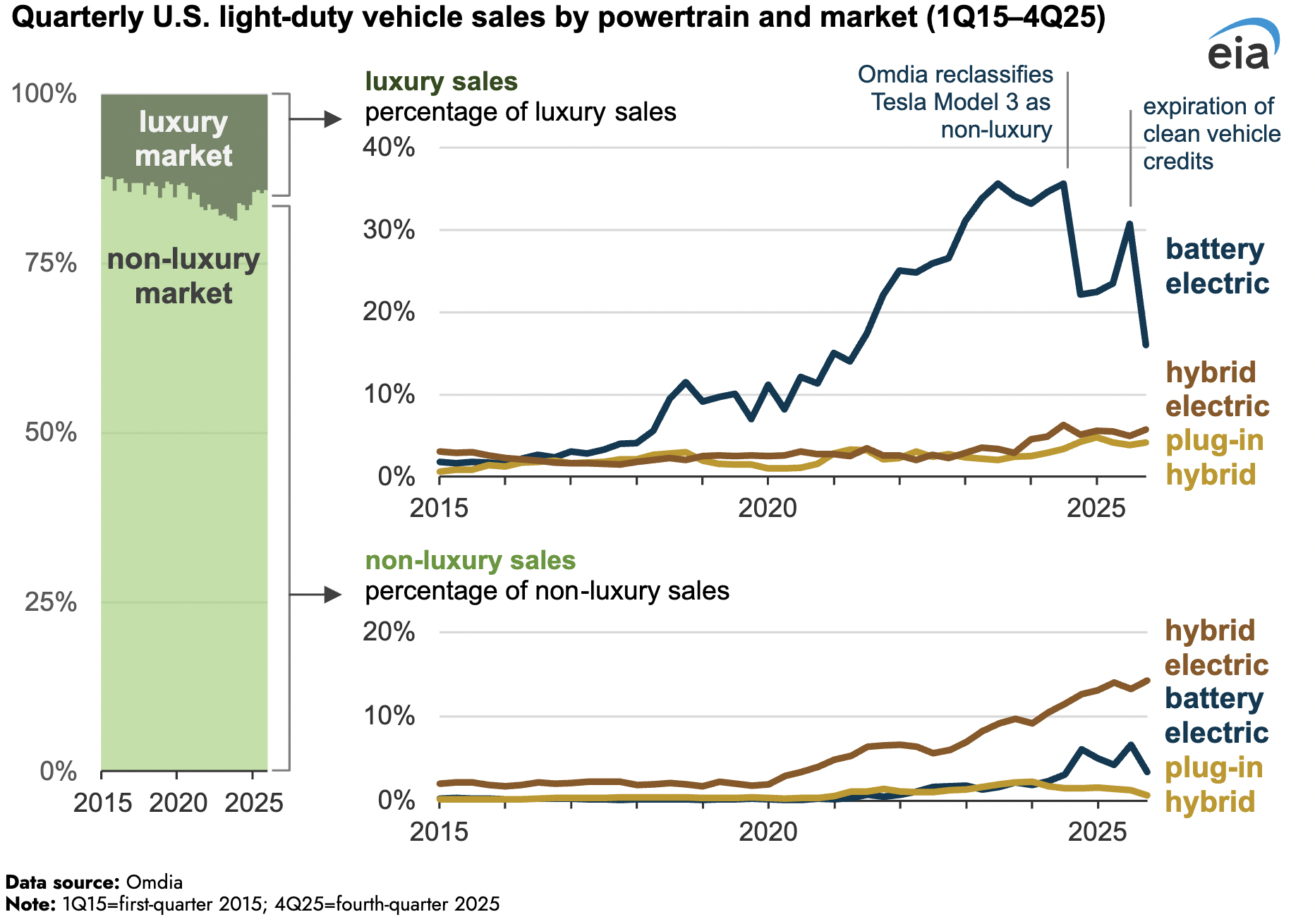

Two tax credits for purchasing or leasing new electric vehicles both expired on September 30, 2025: the New Clean Vehicle Credit and the Qualified Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit. Battery electric vehicle market share reached record highs immediately before the credits expired: 12% of light-duty vehicles sold in September. Battery electric vehicle sales then fell to less than 6% of the market in each of the remaining months of 2025. Last year marked the first year where annual sales and market share of battery electric vehicles declined.

Battery electric vehicle sales in particular are more common in the luxury vehicle market. U.S. luxury vehicles accounted for 14% of the total light-duty vehicle market in 2025, and within luxury sales, battery electric vehicles accounted for 23%. The expiration of the clean vehicle tax credits affected sales of luxury and non-luxury battery electric vehicles in similar ways.

Because sales figures in any year are relatively small compared with the total number of vehicles on the road, electric vehicles’ share of the total light-duty vehicle fleet is much less than the recent 9% sales share (7.5% battery electric vehicles and 1.6% plug-in hybrids). In our Monthly Energy Review, we maintain annual data series on light-duty vehicles, battery electric vehicles, plug-in hybrid vehicles, and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles based on data from S&P Global. In 2024, the most recent data year, electric vehicles accounted for 2% of all registered light-duty vehicles in the United States.