Connecticut environmental officials are pushing for legislation that would grant condo owners and renters the right to install their own car chargers, part of a broader effort to dramatically expand the state’s electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

The so-called right-to-charge legislation would prevent condominium and homeowners’ associations, as well as landlords, from prohibiting or “unreasonably” restricting residents who have a designated parking space from installing charging equipment.

Individual residents would be responsible for paying all of the costs associated with the purchase and installation of a charger, which can easily exceed $1,000. But a new state incentive program launched in January could help defray the expense.

Homeowners can receive rebates of up to $500 for a Level 2 charger, as well as up to $500 for any electrical upgrades that might be needed. Various incentives are available for multi-unit rentals, either through the landlord or tenants. Participants can also receive additional credits for charging their vehicles in off-peak hours under demand response programs administered by Eversource and United Illuminating.

A right-to-charge law will help ensure that “the opportunities available to single-family home dwellers to own electric vehicles and participate in demand response programs are also available to those who live in multi-unit dwellings,” about 11% of Connecticut residents, said state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Commissioner Katie Dykes in testimony submitted to the legislature’s Energy and Technology Committee.

At least eight states have similar laws in place: New York, New Jersey, California, Hawaii, Virginia, Oregon, Maryland and Florida.

But at a recent public hearing on the Connecticut bill, organizations representing condominium associations and landlords opposed the measure, saying it is a “one size fits all” approach to housing developments that vary widely in size, layout, infrastructure and parking availability.

Andrea Dunn, a condominium association lawyer from North Haven, said installing individual chargers “may be impossible” in some communities due to challenges such as a lack of an electrical source close to parking areas, thereby requiring the digging up of land, sidewalks and other common elements.

“Even if the unit owner is paying for it, it affects other members of the community,” she said.

Karl Kuegler, Jr., director of community association management for Imagineers LLC, which manages about 200 common interest communities in Connecticut, said many of the standalone garages with multiple bays commonly found at these complexes “have barely enough electricity to supply the lighting and a couple of utility outlets within the building.”

Condominium lawyers had similar concerns when right-to-charge legislation came before New Jersey lawmakers in 2020, but they were able to amend the language to address those issues, said Matthew Earle, an attorney who chairs the legislative action committee for the state chapter of the Community Association Institute.

For example, “one big concern was that older complexes may not have the electrical infrastructure sufficient to handle more than a couple of chargers,” he said.

So the law includes a provision that says if charger installations are going to require infrastructure improvements to provide a sufficient supply of electricity, the association can assess that cost to the charger owners in a pro rata way.

Since its passage, Earle says he has not heard any reports of negative impacts. At the same time, he also hasn’t seen many car charger applications within the communities he works with. Instead, the trend is toward associations installing communal car chargers.

“They are taking advantage of a state program that will provide up to $30,000 to install one — it’s very popular right now,” Earle said. “It seems like a better way of doing it.”

In such cases, buildings partner with a third-party vendor that provides the software that regulates the station and charges vehicle owners for plugging in, he said.

Connecticut’s charger incentive program offers up to $20,000 for charging equipment installed at a multi-unit development, and up to $40,000 in underserved communities.

But communal chargers run by third-party vendors may not be the most equitable solution in buildings that house people of lower means, said Marc Geller, a co-founder of Plug In America, a national nonprofit advocacy group for electric vehicle drivers.

“The real problem with a third party doing it is that folks in multifamily housing end up paying more for electricity to charge their car than folks in a single-family home,” he said. “Solving this problem for multi-family homes is a major equity concern, and there is not just one solution.”

Right-to-charge laws “go some way to give folks the possibility of installing charging, but it can be quite expensive to do it,” he said.

Where possible, he said, he believes the best approach is to connect a parking space to an individual unit’s meter, so that the resident can simply charge on a regular 120-volt circuit. It’s slower than a Level 2 charger, but it allows the resident to charge at utility rates and without a lot of additional expense, he said.

Gannon Long, director of policy and public affairs at Operation Fuel, which provides energy assistance to low-income households in Connecticut, said she hasn’t heard that the right to charge is of any concern to the financially burdened residents of environmental justice communities.

“People aren’t worried about their right to charge — they’re worried about electricity and heating costs,” she said. “And most electric vehicles are way too expensive for most people to afford.”

Right-to-charge language is also included in Senate Bill 4, a comprehensive package that includes a host of measures to drive electric vehicle adoption, including expanding the state electric vehicle rebate program, and setting goals to electrify all school buses and state-owned vehicles. A public hearing is scheduled for Friday.

Shipbuilders in the port city of Brownsville, Texas, are nearing the halfway mark on shaping 14,000 tons of steel into a vessel designed to ensure the country’s gamble on offshore wind is less dicey.

Meanwhile, 1,676 miles east in Virginia, executives with Richmond-based Dominion Energy who ordered the ship have their fingers crossed.

They are hopeful home-state regulators will greenlight a request by their subsidiary, Dominion Energy Virginia, to deploy the $500 million colossus to “plant” the country’s hugest — and Virginia’s first — full-scale commercial offshore wind farm beginning in summer 2025.

Dominion has dubbed its hulk Charybdis, after the daunting sea monster of Greek mythology. Eventually, the brawny, 472-foot-long vessel will be equipped with sturdy “legs” that stabilize it on the seafloor and a main crane capable of toting 2,200 tons — the equivalent of 4,400 grand pianos.

The looming challenge of efficiently securing 176 mega-turbines to the ocean floor off the coast of Virginia Beach is what prompted the parent company to dip its corporate toe into ship construction.

After enduring a convoluted but ultimately successful process to install its precursor two-turbine pilot project in 2020, Dominion decision-makers are confident that investing in the nation’s first specialized installation vessel is wise — and potentially lucrative.

“The pilot helped educate us,” said Charlotte McAfee, director of construction projects at Dominion who has guided progress on Charybdis since early October. “It showed us that this commercial project is really best managed with a vessel with a U.S. flag.”

Even if the State Corporation Commission nixes the utility’s proposal for Charybdis to install what’s known as the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind (CVOW) project, Dominion doesn’t expect the giant expensive ship to sit idle.

In fact, it is already chartered to handle turbine installation duties for two separate offshore wind projects in the Northeast slated to be completed before Dominion’s 2,640-megawatt farm.

As well, Dominion figures Charybdis can continue to be a workhorse as the Biden administration has set a goal of reaching 30 gigawatts of wind power by 2030 along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and in Pacific waters.

“Dominion has really been pioneering on this front,” McAfee said. “I’m proud to be part of it.

“We’ll find good uses for the vessel whether we’re permitted to use it for CVOW or not. The market is ready for the whole United States and this is the best way to install renewable energy.”

One monumental hurdle to harvesting the ample wind along U.S. coastlines is the lack of homegrown industries that craft the foundations, blades, nacelles (which house the generating parts) and other distinctive components fitted together to create the sophisticated turbines. Now, they withstand lengthy and expensive journeys from Europe, where the industry has matured.

Another key obstacle is the obscure Merchant Marine Act of 1920. Known as the Jones Act, it shields domestic shipbuilding enterprises by restricting water transportation of cargo between U.S. ports to American-built and -owned vessels crewed by U.S. citizens.

Charybdis represents Dominion’s commitment to advancing American offshore wind out of its longtime infancy.

Offshore wind is crucial if the investor-owned utility’s portfolio is expected to achieve 100% carbon-free electricity generation by 2045, as required by the 2020 Virginia Clean Economy Act. The utility is also intent on reaching net-zero carbon dioxide and methane emissions goals by 2050.

The Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project, scheduled to go online in 2026, will power the equivalent of 660,000 homes.

Karl Humberson, a marine engineer hired by Dominion in 2011, oversaw progress on Charybdis before McAfee inherited those duties. He is responsible for the installation and construction of the wind farm.

Four years ago, the company tasked Humberson with exploring potential turbine installation solutions. In May 2020, Dominion announced it was leading a consortium to build a Jones Act-compliant vessel. By autumn, the company had contracted with the global firm KeppelAmFELS to build Charybdis in Texas.

Humberson is aware insiders and outsiders are curious why an energy company took the initial plunge on a vessel that might not even ply Virginia’s coast.

“Let’s take a couple of steps back and look at CVOW,” Humberson said. “The idea is that this is something necessary and aligns with Dominion’s renewable energy and sustainability goals.”

Investing in a “purposeful vessel,” he said, is a boon for all U.S. players intent on advancing wind.

“If you want to be successful, you want to have the right tools,” Humberson said. “What we’re saying is to expand the industry, here’s the only right way we know to do it right now.”

Assembling and installing the pilot — a pair of 6-megawatt turbines in federal waters adjacent to the larger wind farm — was a logistical headache due to lack of a Jones Act-compliant ship.

First, the components manufactured in Europe made a transatlantic journey on a cargo ship, the Bigroll Beaufort, which docked in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

There, the foundations were offloaded onto an installation vessel, the Vole-au-vent, and transported to the construction site off the coast of Virginia. Then, that same vessel completed a second trip from Canada with the turbine components on board.

“This time, we’ll have 176 turbines, not two, so coming down from Canada would not make a lot of sense,” Humberson said.

Without Charybdis in the picture, an alternative method is to put the components on a barge and transfer them to an onsite European vessel that could serve as the installation base.

“Using a barge and tugboat means double-handling everything,” Humberson said, emphasizing that turbine blades are fragile. “If you need to move this equipment, you want to do it once and you want to get it right.”

One of Charybdis’s benefits is providing an extremely stable work platform whether seas are calm or choppy, he said.

The height and weight of components are serious considerations. For instance, blades for the pilot project measure 253 feet. The monopile foundations are 220 feet long and weigh 1,000 tons apiece.

Those measurements are diminutive when compared to the heavy lifts in store with the commercial project. For instance, the turbines — the largest available — have a capacity up to 14.7 MW. Just one of those turbines has more generating capacity than the entire pilot project.

A blade alone measures 354 feet — longer than a football field. And just the visible part of each turbine is skyscraper height, stretching a soaring 800 feet from the top of the ocean to the tip of a blade pointed straight up.

David McFarland, Dominion’s director of investor relations, knows $500 million is a whopping price tag for anything, never mind a unique Jones Act-compliant ship.

“What Dominion Energy is doing is showing confidence in the offshore wind industry” and opportunities for it to thrive domestically, McFarland said.

The question he fields most often: Who is footing that bill?

It’s not ratepayers — at least not directly. Instead, the ship is being built for the mammoth parent company that owns multiple subsidiaries nationwide, including Dominion Energy Virginia.

The majority of capital for funding Charybdis is being borrowed from third parties and banks, McFarland explained, adding that “making payments to banks is a shareholder expense, not something passed on to a utility customer.”

Leasing out Charybdis to other coastal wind projects allows the parent company to reap a return — somewhat indirectly — on that $500 million investment.

For instance, Dominion Energy Virginia has folded the cost of leasing — not building — Charybdis into its request before state utility regulators seeking the go-ahead for the entire $9.8 billion wind farm project.

“That lease is included in the cost of [the wind farm’s] construction,” McFarland said. “It’s spent on behalf of customers and is expected to be recovered from customers. Dominion Energy Virginia is looking to recoup that money.”

He is convinced Charybdis is a boon for the company’s utility customers.

“They’re better off with this vessel, because otherwise the cost [of turbine installation] would be higher,” McFarland said. “You do want the best solution for customers.”

Charybdis is on track to be completed on schedule by December 2023, McAfee said.

Thus far, Ørsted and its joint venture partner Eversource, are the first to book Charybdis for its Revolution and Sunrise wind projects. Their construction and operations plans are undergoing environmental review now.

Revolution is a 704-megawatt project designed to serve customers in Connecticut and Rhode Island, while Sunrise will provide electricity to New Yorkers. Both are expected to be operating by 2025.

Ørsted, a global leader in the wind industry, has also partnered with Dominion on both of its wind projects.

Dominion said it was unable to provide figures for the daily rental fee required because those numbers are “competitively sensitive.”

Willett Kempton, a professor at the University of Delaware who is a nationally renowned expert on offshore wind power, said wind developers negotiate those fees with Dominion.

Kempton said in an interview that he had heard from industry sources that those daily rates could be as high as $500,000, but didn’t know how accurate that number will turn out to be.

The daily fee for using a non-U.S.-made installation vessel is likely close to $250,000, he said.

While $500 million is a hefty sum to invest in a vessel with Charybdis’ capabilities, Kempton said somebody had to go first seeing as “this is the only way the industry knows how to do installations.” One such installation ship likely won’t be enough if the U.S. wind industry booms as expected, he added.

Companies without access to Charybdis or a similar vessel will likely resort to a feeder barge system as a stopgap solution to keep their wind projects on schedule, he said.

The Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management has approved construction and operations plans for two other offshore projects: 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind in Massachusetts and 130-megawatt Southfork Wind in New York.

By 2025, the agency has vowed to advance new lease sales and complete review of at least 16 construction and operations plans, which represent more than 19 GW of renewable energy.

Charybdis will be based in Hampton Roads and staffed with U.S. crews. It’s one enormous piece of Virginia’s attempt to transform its existing regional advantages — a robust maritime workforce and a port in Norfolk with deep water and no height restrictions — into a supply chain hub.

“The supply chain is in Europe,” Humberson said. “There’s a lot of talk about building it up in this country, but it’s not here yet.”

As evidence, he pointed to Germany, Denmark, Finland and Italy as sources for turbine components and affiliated infrastructure. Most of it is destined for a 72-acre site at the Portsmouth Marine Terminal. That space will serve as a staging and pre-assembly area, courtesy of a 10-year lease with the Virginia Port Authority.

The terminal also will house a blade-finishing factory operated by Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy, the company contracted to deliver the 176 CVOW turbines. That work entails sanding and adding protective coatings to the prebuilt blades.

Beginning in 2024, while Charybdis is readying for the two wind projects in the Northeast, Dominion plans to begin driving turbine foundation monopiles into the ocean bed at the 112,800-acre CVOW lease area. The site begins 27 miles offshore and extends 15 more miles out into the Atlantic.

The largest of those 176 steel monopiles, manufactured in Germany by EEW Special Pipe Constructions, is 268 feet long and weighs 1,755 tons. Into 2025, a separate company will transport, position and secure those foundations without the aid of Charybdis.

To protect the North American right whale, the window for that underwater chore is between May 1 and Oct. 31, per National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration regulations.

When Dominion’s McAfee graduated from law school at Washington & Lee University in 2004, she figured pumps and suits would dominate her career wardrobe.

That changed after the young attorney was hired by the utility a decade ago. Eventually, she began amassing steel-toed boots as she pivoted to electric transmission and distribution projects.

Those boots are again serving her well for her regularly scheduled trips from Richmond to the Brownsville shipyard to monitor Charybdis’ progress.

“It’s not like I’m inspecting the welds, but I’m getting a sense of what I need to be coordinating at the shipyard,” she said. “In-person visits keep the communications open and candid.”

Devotees of Homer’s ancient and epic poem “The Odyssey” know that the mega-ship’s ferocious namesake lurked in a narrow passage between the island of Sicily and the toe of Italy’s boot. The monster was reputed to swallow the sea three times daily, causing a whirlpool that thwarted the protagonist as he sailed home from the Trojan War.

Part of McAfee’s job is ensuring that this version of Charybdis doesn’t wreak any such havoc before it’s ocean-bound.

So far, so good, despite two challenges. One was covering for her lack of maritime experience by burrowing into volumes about shipping. And the other was navigating an immense undertaking in the thick of a pandemic.“As far as the construction goes, Charybdis is a teenager now,” she said. “It’s just an honor to be involved. Once we’re finished, it will be ready to self-propel to Hampton Roads.”

Burlington, Vermont’s municipal electric utility is expanding a program that gives apartment renters more access to electric vehicle charging.

Originally launched as a pilot in 2019, the program gives apartment building owners a financial incentive to install chargers and make them available to the public. The chargers use a software called EVmatch, which drivers can access through a smartphone app to reserve and pay for charging times.

“The primary focus here is to benefit customers of Burlington Electric who are renters or residents of a multifamily condo building,” said Darren Springer, the utility’s general manager. He said 60% or more of Burlington Electric’s residential customers rent apartments, and the utility wants to make it easier for them to drive electric vehicles.

Springer added that the program could benefit the broader public — not just Burlington residents but drivers who are passing through as well.

The new program is expected to roll out in the coming weeks. Building owners who install a smart charger compatible with EVmatch can get a $1,200 incentive to cover installation. If it’s a building that serves low-income residents, the owner can get an extra $250. And if they make the charger available to the public, they can get an extra $300.

The incentive will be available for each charger the building owner installs, covering up to 75% of the installation cost for each charger. Springer expects it will cover a little more than half the cost of the charger and installation in most cases.

Building owners can choose a charger that’s not compatible with EVmatch and just make it available for tenants to use at no additional cost, in which case they could get a $1,000 incentive toward installation and the extra $250 if they serve low-income residents.

Springer described the program as “a real success story for bringing these different seed stage energy companies to Vermont” through the DeltaClime accelerator program. DeltaClime each year provides funding and mentoring to new energy-focused companies, and the 2019 round led to the pilot that Burlington Electric launched with EVmatch.

Through EVmatch, a sort of Airbnb for electric vehicle charging, owners of compatible chargers can make them available for drivers to reserve. The owner of the charger sets the price — they can charge just for the electricity or make a profit by selecting a price markup.

The pilot in Burlington, which began with 14 chargers at apartment buildings, condos and other multifamily residences, was the first time EVmatch deployed a feature that lets owners allow different groups to use the charger at certain times and prices. In other words, a building owner could make the charger available at any hour to tenants and make it available to the public only during the daytime.

In the original pilot, building owners received a $500 incentive toward installation of a publicly available EVmatch-compatible charger. Ten chargers in the original program were made publicly available, leading officials to believe many chargers under the new program will likely be made publicly available.

Springer said officials are confident the program will be successful since the pilot demonstrated demand for chargers by building owners and drivers. “The EVmatch pilot demonstrated for Burlington Electric that the approach EVmatch offered in terms of software, billing and their app worked well for our customers and for participating multifamily, rental and condo buildings,” he said. “It gave us real-world data and experience with EVmatch’s technology.”

He added that the utility’s customers have expressed interest in expanding charging for the public, for low-income residents and for apartment renters. “This program is aimed at doing exactly that,” he said.

Funding for the new program comes through expanded flexibility for Vermont’s efficiency utilities (which includes Burlington Electric) to fund programs that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as well as from Burlington Electric’s “Tier III” budget. This segment of the budget requires electric utilities to use a certain percentage of sales for projects that reduce fossil fuel use. The program has been budgeted to support about 50 to 60 chargers over the next two years, but Springer added that the budget could be amended if there’s higher demand for chargers.

According to Heather Hochrein, EVmatch’s CEO, making the charger public can serve as a financial buffer for building owners who want to install chargers when their tenants don’t yet have the cars to use them. Conversely, once the chargers become available, tenants might be more willing to get an electric vehicle.

“We’re very excited about this new program,” Hochrein said. She said the pilot in Burlington demonstrated that chargers in multifamily buildings are being used by the public. The incentive Burlington Electric is offering building owners to install chargers is helpful to increase uptake of EVmatch, she added.

The California Energy Commission last year awarded a grant to the company toward the installation of 120 EVmatch-enabled chargers at multifamily buildings in the state. The chargers will be made publicly available using the same user group feature originally launched in Burlington.

Damon Lane, who owns a four-unit rental property in which he lives and rents out the other units, was one of the original participants in the program.

“My intention was always for it to be publicly available,” he said. Neither Lane nor any of the people living in his building own an electric vehicle. But since it’s located near Burlington’s downtown and in a residential area where many people rent apartments, he thought it could be useful for the public.

Through the pilot, Lane got an Enel X JuiceBox charger. The chargers were provided free through the program to owners of multifamily residences, but he paid $30 to get a higher-power charger than what was offered through the program. (It would have cost about $680.) He also received the $500 incentive toward a $910 installation for making it public.

These incentives helped him substantially, he said, because “unless I was going to charge an outrageous rate [on EVmatch], I was never going to recover the installation cost.” And with the EVmatch software to help with booking and billing, he said, “it is quite easy to provide this service to the community.”

A bill progressing through the Wisconsin legislature was meant to spur the expansion of electric vehicle charging by confirming that private businesses can sell electricity to drivers at charging stations.

But amendments to the bill have turned electric vehicle proponents against it. The current version would ban government entities from owning or leasing charging stations and would only allow stations to charge for electricity that comes from utilities — not from on-site solar installations.

Clean energy proponents including Renew Wisconsin now say they want Gov. Tony Evers to veto the bill if it passes the legislature with those provisions intact. The Assembly version of the bill has passed committees and could be heard by the full House in coming days.

Scores of private businesses in Wisconsin currently own EV charging stations and bill customers for the energy. But advocates fear utility opposition could shut them down at any moment, especially if utilities decide to build their own charging networks, potentially earning a rate of return in the process.

As a shift to electric vehicles appears increasingly inevitable, the Wisconsin debate highlights the growing fight across the country over who will control and benefit most from that transition.

The situation has much in common with the state’s long-standing angst over third-party-owned solar installations. Utilities have argued such arrangements infringe on their exclusive rights to deliver power to customers, hence third-party solar is essentially impossible in Wisconsin even though no law bans it. A bill currently before lawmakers would clarify that third-party solar ownership is legal, and another bill would facilitate community solar with third-party ownership. The EV bill in the state Senate was introduced by Sen. Robert Cowles, a Republican who is also the lead sponsor of the third-party-solar bills.

“All three bills have this thread of the utility wants to make sure nobody can sell any kind of electricity in any form,” said Jim Boullion, government affairs director of Renew Wisconsin. He noted that at least 34 states have laws specifically differentiating EV charging from utility service. He said only five states — Iowa, Kansas, North Dakota, South Carolina and Virginia — have adopted policies restricting EV charging station ownership beyond utilities.

“We’re talking about a different industry than the ‘obligation to serve’ that the utilities have — they’re now expanding into transportation fuels,” Boullion continued. “We think the regulatory system is good and we need it, but the way things are changing in the world, having these strict limits is really hampering the growth of this clean affordable energy source. There has to be some flexibility in the model we’ve had for 120 years to acknowledge this new technology.”

Companion bills SB573 and AB588 explicitly allow private entities to own EV charging stations and bill customers for connecting to them (or “parking near” them). The bills also specify that billing can be done by either time or amount of energy used. Clean energy advocates want to clarify that billing by kilowatt-hours is indeed legal, since billing by time disadvantages customers with cars that charge more slowly or customers charging in cold weather (which slows charging speed).

Legal clarity can further the spread of charging stations across the state, advocates argue, especially as the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act could mean up to $79 million over five years for EV charging in Wisconsin, according to Renew’s analysis. There are currently 379 public charging stations (level 2 or DC fast-charging) in Wisconsin, according to the Alternative Fuels Data Center. They are most heavily concentrated in the southeast and tourist-friendly Door County, with relatively few in the northern half of the state.

As eager as they are for clarification, advocates say the status quo is better than a law that bans sales from government-owned charging stations or charging stations powered by solar. (The bill would still allow both types if they don’t sell power.)

The bill would mean cities and towns could not build for-pay charging stations in municipal parking garages or along commercial strips, for example. The League of Wisconsin Municipalities representing almost 600 towns and cities notes in a letter to legislators that it will revoke its original support of the bill if the amendments remain intact.

League government affairs director Toni Herkert framed it as an issue of equity in her December 2021 letter:

“A complete prohibition against municipalities owning, operating, managing, leasing, or controlling EV charging facilities does not allow for all areas of the state to be reliably served with charging facilities. Limiting entities that can provide charging facilities will simply result in the most profitable areas, where the market dictates successful investment, to be reliably served. We do not want electric vehicle charging opportunities to mirror the lack of market incentives witnessed for broadband investment in rural areas, it will again be those smaller and more rural communities that will be most impacted and under or unserved.”

Flo, a company that develops EV chargers along roads, also opposes that provision. In a letter, Flo senior public affairs specialist Cory Bullis said that such curbside charging stations are often built by local governments to encourage patronage of local commerce.

“Businesses aren’t motivated to single-handedly spend their own money on an asset that will benefit their competitors on the same block, nor are they willing to take on liability of owning an asset that is permitted on public property,” wrote Bullis. “City governments can step up to provide this value to multiple businesses simultaneously, ensuring everyone benefits.”

Bullis noted that Montreal has almost 1,000 curbside chargers, while New York City has 120 and Los Angeles has 200.

“The EV charging industry is still young and quickly evolving; this provision picks winners and losers among EV charging business models by expressly locking us out of the state,” Bullis wrote.

Advocates worry the bill would exacerbate drivers’ “range anxiety,” since the ban on for-pay charging stations owned by the government or powered by solar would make it harder to locate stations in remote and rural areas.

“If I’m going to the state park up north and have solar plus storage [powering an EV charger], then I do not have to run high-power lines out there” to install a charger, said Boullion.

The bill also would prevent businesses with their own solar panels from receiving payment for EV charging, unless they install a separate meter to ensure that no power from the solar panels goes to the EV charger, Boullion explained.

This could be a disincentive for the proliferation of both solar installations and EV charging stations, and it would curb rather than encourage the ideal clean transportation solution: vehicles powered directly by solar energy.

Bergstrom Automotive, a company in Neenah, Wisconsin, has an on-site microgrid capable of generating and storing up to 23 megawatt-hours of solar annually, enough for almost 500 electric vehicle charge-ups. The development was done by EnTech, a Wisconsin-based company that has also installed solar-plus-storage EV charging at a Madison shopping mall.

Even if businesses or governments sell some behind-the-meter or off-grid solar power to electric vehicles, without utilities getting a cut, advocates argue that EV proliferation is bound to be a boon for utilities. Solar-plus-storage arrangements helping to power EVs can reduce demand spikes and stress on the grid, and even power emergency vehicles or provide extra energy during outages, Renew said in testimony submitted to the legislature.

And the more charging stations there are available, the more people will feel comfortable buying electric vehicles. In most cases, the entity charging for use of the charging stations will be first buying that electricity from the utility. Meanwhile, utilities should also see their demand increase as more and more cars are charged at home.

“The utilities will gain a lot of business out of this,” Boullion said. “They will sell a lot of extra energy.”

A two-year-old economic development partnership is helping to draw attention — and investment dollars — to sustainability projects in the Great Lakes region.

The Great Lakes Impact Investment Platform was launched by the Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers. The alliance of U.S. and Canadian officials from Québec to Minnesota is focused on growing the region’s economy and protecting its fresh water.

The investment platform is helping to do both, promoting investment opportunities that benefit the environment, including renewable energy, clean water, and ecological restoration. The platform features 40 projects representing nearly $4.5 billion in investments, including household energy efficiency retrofits, coal mine reclamation, and utility-scale solar development.

“Global capital markets are hungry” for chances to invest in green projects, said Dave Naftzger, the conference’s executive director. But financial institutions, philanthropic entities and others have long looked to the coasts for such opportunities.

Great Lakes states offer untapped potential that can pay off for investors as well as regular citizens and the environment, Naftzger said. And even with increasing federal action, including incentives and programs under the new U.S. infrastructure law, a swift and equitable clean energy transition will still depend on private investment and public-private collaborations.

“Especially for investors who care about water, they should look to the Great Lakes as a matter of course,” Naftzger said. Meanwhile, clean energy-related investments are also a robust and growing sector, including projects tapping green bonds, property assessed clean energy programs, and other financial tools to leverage public and private funds.

The platform is something of a matchmaking service, publicizing green investment opportunities and projects and helping to connect funders and lenders with these initiatives, while also allowing projects to learn from each other.

Among the energy-related projects showcased by the platform:

Such green investing helps developers, governments and even individual households access capital that they might not have been able to otherwise. And it allows financial institutions and other funders to meet environmental and sustainability goals and serve clients who want their money to go into green efforts.

“There’s a lot of place-based investors — people who are specifically looking for opportunities here” in the Great Lakes, Naftzger said. “That could include pension funds, high-net-worth individuals, family offices, community foundations, philanthropic organizations. And these deals can provide market returns or better. … We’re helping people understand the opportunity — it’s a relatively new one, but people are becoming aware of it.”

Michigan Saves is essentially an independent, nonprofit green bank that lends to individuals, businesses, and municipalities for solar, energy efficiency and geothermal projects, with loans ranging from $1,000 up to $100,000 and into the millions for commercial projects. It was started to help Michigan meet ambitious energy efficiency targets in 2008 legislation, and has done $325 million worth of financing since the first loan in 2010, President and CEO Mary Templeton said.

The state government offers public funds to secure loans made by private lenders, including small credit unions, so that they can lend with little risk — and if someone defaults, the government pays. This was especially important since the program launched in the wake of the 2008 economic crisis, when lenders were skittish. So far the default rate on loans is only 2%, Templeton said.

The lending process is meant to be streamlined and fast so that, for example, if someone’s furnace breaks, they can buy a more energy-efficient furnace quickly enough to stay warm.

Templeton said such convenient and accessible loan offerings can actually convince people to invest in energy-efficient products when they hadn’t otherwise planned to.

“An electric heat pump, solar panels — those cost money — nothing is forcing you to do that,” she said. “But when we can make it more attractive, we’ve seen a large demand.”

Michigan Saves helped a Kalamazoo art gallery and jewelry store owner install efficient LED lighting that also makes her products look nicer, helped a young couple insulate their drafty first home, and helped a family save $600 a year and live more comfortably with a new furnace and retrofits, among many stories featured on their website. Energy consumption was lowered in every case.

Michigan Saves also works with lenders to establish third-party-owned solar projects, wherein the lender sets up an LLC that owns a solar installation to tap tax credits that aren’t available to nonprofits, and to relieve the customer of up-front costs. The program also partners with utilities to offer zero-interest loans to businesses for energy efficiency improvements. Those improvements help utilities meet their own energy conservation mandates.

“For small businesses in particular, like restaurants, they can implement basic [efficient] lighting in parking lots, they can get efficient HVAC,” she said.

Michigan Saves is part of the American Green Bank Consortium, which includes publicly and privately run green banks in states including New York, Delaware, Connecticut, Nevada, California, Hawaii and Louisiana, though few in the Midwest.

“We learn and share best practices — I get calls all the time from people thinking about setting up green banks,” Templeton said. Among other things, callers ask about “the way we structured loan loss reserve, and credit enhancement that leverages $30 of private investment for every $1 of public investment. That’s a pretty amazing ratio.”

Michigan Saves works with a network of providers for insulation, air sealing, solar and energy storage, electric heat pumps, lighting, and other sectors. The website allows customers to read reviews and connect with contractors.

“It really helps to support local jobs,” Templeton said. “These are jobs that can’t be anywhere but in our backyard.”

Like many utilities, DTE is quickly expanding its renewable holdings with utility-scale solar and wind farms. In 2021 alone, it added 535 megawatts of renewables, enough to power nearly 700,000 homes.

And DTE is helping to lower the costs and raise awareness of those investments through green bonds, wherein financial institutions buy bonds that pay for the renewables and earn a set rate of return as the utility pays off the bonds.

The bonds can be issued for projects that have already been constructed, noted DTE corporate financial specialist Kathleen Hier, eliminating the uncertainty that might exist for a planned project.

DTE manager of corporate finance Scott Bennett explained that the bonds are typically purchased by insurance companies that specialize in green debt and likely hold green bonds from other utilities as well. Those companies may also sell the bonds on secondary markets.

While DTE could and would have built renewables even without green bonds, they can tap more favorable rates since offering a green bond attracts investors who are seeking green financial products for their portfolio or secondary markets.

“When we issue the green bond, these [green-oriented] funds are creating more demand for that issuance because we have normal bidders, and also green funds, so hopefully we see better pricing,” he said. “There’s just more demand out there — when we do a green bond versus a regular bond, we may have six more funds bidding in.”

Swaths of once fertile or forested land across Great Lakes states and Appalachia have been turned into barren wastelands by coal mining. But efforts are underway to meaningfully reclaim and replant some of this land. The green investment-focused firm Quantified Ventures is looking to transform formerly mined land by leveraging carbon markets.

Quantified Ventures received a grant from a U.S. Department of Agriculture program to nurture the soil and then plant trees on previously mined land in Pennsylvania and possibly also Ohio, West Virginia or Kentucky.

The company used the Great Lakes Impact Investment Platform to help spread the word to investors about a pilot project they had originally planned, which will now be greatly expanded thanks to the federal funding. The company will use its own financing to augment the federal funds, and recoup costs through selling carbon credits from planting trees, including through a mechanism that allows up-front payment.

Quantified Ventures managing director Todd Appel said they hope the effort can be a model for other investors, organizations and companies to use carbon credits and voluntary carbon markets to finance mine reclamation and reforestation — a linchpin to “just transition” movements across coal country including in Illinois and Indiana.

“The mining has scarred the landscape. There are limited plants and trees — it’s not a healthy habitat for birds,” Appel said. “So we’re going to rip up [and replace] the soil to enable planting of new trees and identify landowners to participate.”

The previously mined land might be owned by governments, companies or individuals who have acquired it. In such an arrangement, an entity like Quantified Ventures would likely provide financial incentives to the landowner to get an easement, and the entity paying for the reforestation would recoup their costs and earn a return through the carbon credit sales.

“We’ll seek to scale this up. There are millions of acres this could be applied to,” Appel said. “The other goal is to prove carbon markets can enable this work.”

Correction: Mary Templeton is president and CEO of Michigan Saves. An earlier version of this story misstated her title.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Automakers are planning to put nearly 1 million new electric vehicles on American roads in 2022. Lawmakers are trying to make sure their states are ready.

“We will see a lot more emphasis on electric vehicles in 2022 and 2023,” said Dylan McDowell, deputy director of the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators, a collaborative forum for state lawmakers. “This is the start of a really big turning point.”

Across the country, legislatures in blue and red states are considering bills to bolster charging infrastructure, expand consumer incentives, electrify state fleets or mandate charging stations in new buildings. States also will be tasked with deploying billions in new federal funds for charging stations approved in the new infrastructure law, and some legislators say they plan to take an active role in that strategy.

“Every state is involved,” said Marc Geller, a board member and spokesperson for the Electric Vehicle Association, an advocacy group that promotes the adoption of such vehicles. “This is being taken seriously in a way it hasn’t been before, because the trajectory is very clear.”

In the United States, the transportation sector is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, making up nearly 30% of the national total. While many states have plans to switch to renewable electricity sources, reducing vehicle emissions — with millions of drivers making personal buying choices about their cars — is much more complicated. But as the private-sector market for electric vehicles matures, many lawmakers see an opportunity.

Electric vehicle sales in the United States doubled in 2021 compared with 2020, and car buyers in 2022 will have twice as many electric models from which to choose. As the market grows quickly, state lawmakers say they’re focused on making sure infrastructure keeps up, and — in what is perhaps the greater challenge — ensuring that electric vehicle benefits aren’t just enjoyed by their wealthiest residents.

State leaders of all political stripes say they want to ensure their states are ready for the electric vehicle transition. Democratic-led states have typically been more aggressive about that transition through government regulation and mandates, such as the stringent emissions standards set out in California’s Advanced Clean Cars Program. Many Republican states have invested in other efforts such as charging infrastructure and conversion of state vehicle fleets.

Still, some Republicans argue that market forces, rather than public investments or mandates, should be left to work. Some GOP-led states have introduced or passed bills to block their local governments from requiring charging stations in certain locations.

Hawaii ranks No. 2 in the nation behind California for electric vehicle adoption, and lawmakers there are especially active in pushing a suite of proposals to strengthen that transition.

“We’re just at the inflection point where we’re about to take off in a huge way,” said Hawaii state Sen. Chris Lee, the Democrat who chairs the Transportation Committee. “Our charging capacity has been greatly outstripped by the number of EVs out there. We need a lot more capacity, and quickly.”

Hawaii legislators are looking to build more charging stations for rental cars, which make up a significant portion of the tourism-heavy state’s electric vehicles. They’re planning to use federal funds to create charging hubs. Other proposals would put in place a requirement for charging stations in public parking lots and a new consumer rebate for electric vehicle purchases, with a focus on lower-income communities.

Meanwhile, Republican lawmakers in both Indiana and Wisconsin are backing bills that would allow the owners of charging stations to sell electricity by the kilowatt-hour, rather than by the minute—an allowance previously reserved for regulated utilities. That would benefit drivers of slower-charging vehicles. Sponsors say the bills would allow businesses to play a greater role in providing charging infrastructure.

Democratic lawmakers in Vermont also are considering a broad swath of electric vehicle policies, packaged together in the Transportation Innovation Act. The proposal would increase funding for the state’s consumer incentive programs, create a grant program to fund electric school and transit buses, accelerate timelines for electrifying the state fleet, fund grants for charging stations and require large employers to provide charging stations for their workers.

“Our goal is to show our priorities, and we have a lot of different pieces around EVs,” said state Rep. Rebecca White, a Democrat who helped craft the measure. “It might feel like we’re throwing the kitchen sink at it.”

White said the bill’s 60 cosponsors offered it as their “opening salvo” on a transportation package ahead of negotiations with Republican Gov. Phil Scott. Scott’s office did not respond to an inquiry about his stance on the electric vehicle policies.

Many Democratic governors also have put forward electric vehicle proposals as key elements of their 2022 agenda.

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, a Democrat, has proposed $100 million in funding for a rebate program to help drivers afford electric vehicles. The program would provide a $7,500 rebate for new vehicle purchases, with an additional $5,000 for low-income residents. Used vehicles would qualify for a $5,000 rebate. The program would be capped to exclude residents making more than $250,000, and it would not apply to expensive car models.

“A real focus for the governor is making sure we’re increasing access to electric vehicles and not just subsidizing purchases for people who were already inclined to buy electric vehicles,” said Anna Lising, Inslee’s senior energy adviser.

Inslee’s budget also proposes $23 million to build out charging infrastructure and $33 million to help transit agencies switch to “clean alternative fuel” buses.

“I haven’t seen as much engagement [on electric vehicle policies] as I have this year,” Lising said. “We’re starting to see it shift significantly.”

In California, Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom is proposing more than $6 billion in investments to speed up electric vehicle adoption. More than $250 million would be targeted to assist low-income consumers, with another $900 million to build chargers in underserved neighborhoods.

“The [state electric vehicle rebate program] has traditionally been more subscribed [to] by wealthier Californians,” Jared Blumenfeld, secretary of the California Environmental Protection Agency, said in a press call. “In this clean transportation revolution, the next phase is making sure that low-income communities and communities of color are able to take advantage.”

Newsom’s budget also proposes nearly $4 billion to electrify heavy-duty trucks, transit and school buses.

Some Republican governors also are seeking to invest in electric vehicles. Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, for example, has promoted investments in electric vehicles and charging stations. The state’s tax credit for electric vehicle purchases expired last year during the pandemic, and state leaders are considering incentive plans to replace it.

“We have to continue to dramatically accelerate the adoption of EVs,” said Ben Grumbles, the state secretary of the environment. “The focus right now is the range of incentives that we can put in place.”

Grumbles said the Hogan administration also is looking to speed up electrification of the state vehicle fleet, as well as school buses.

Maryland Del. David Fraser-Hidalgo, a Democrat, has long advocated for electric vehicle adoption, and he thinks his colleagues are increasingly on board.

“There’s a critical mass building of more and more EV bills,” he said.

Fraser-Hidalgo plans to introduce an incentive program, likely a tax credit, to encourage consumers to buy electric vehicles. Another bill would allow school districts to partner with utilities to acquire electric school buses.

“It’s not just climate change, it’s public health,” he said. “We’re taking our kids and sticking them in a cube and filling that cube with diesel fumes.”

Other Republican governors have made efforts to ready their states for the electric vehicle transition, but still think government should play a limited role.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, for example, signed a bill in 2020 requiring the state to craft a master plan for electric vehicle charging infrastructure. In 2021, though, he signed legislation that blocks local governments from requiring their gas stations to add charging stations.

The federal infrastructure package Congress passed last year includes $7.5 billion for electric vehicle charging stations, with $5 billion given directly to the states. Some Republicans oppose the use of government funds to support electric vehicle adoption.

“The vast majority of this bill is brimming with wasteful spending that advances radical Green New Deal policies, including billions of dollars for carbon capture programs, federally subsidized electric vehicle charging stations, and zero-emission bus grants for intercity transit,” U.S. Rep. Andrew Clyde, a Georgia Republican, wrote in a news release after the bill passed in the House.

But the funding has gotten the attention of even conservative states that have otherwise shown little interest in climate policy.

Missouri, for instance, will receive $99 million to expand electric vehicle charging over five years from the package. Brian Quinn, a spokesperson for the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, said the agency plans to collaborate with the Missouri Department of Transportation to deploy chargers along national highways. The state also plans to help schools apply for new federal funding for electric buses. States must provide a 20% match for the funds they receive under the federal charging program.

Michigan expects to receive $110 million of the charging funds.

“The federal resources mark a huge turning point for the state of Michigan,” Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist, a Democrat, said in an interview. “This will get a lot of people over the hump in making the choice to have their next vehicle be an EV. This year is going to be the one that makes the difference.”

Lawmakers in Michigan voted last month to create a $1 billion incentive fund to attract economic investment, including the prospect of a battery plant for electric vehicles. The state has partnered with its Midwestern neighbors to form a coalition focused on a regional network of charging stations, and it also is investing in a workforce development plan to ready residents for jobs in the electric vehicles industry.

In New York, state officials expect to receive $175 million from the feds.

“As more EVs are on the road, the business case for installing charging stations gets better and better,” said Adam Ruder, assistant director for clean transportation with the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. “We’re trying to get to that point where it becomes a self-sustaining market. This infrastructure money and the other investments we’re making can really help us get there.”

Some New York officials want mandates. State Sen. Liz Krueger, a Democrat, has sponsored a bill that would require newly constructed buildings to include wiring for electric vehicle chargers in a certain amount of their parking spaces.

“The sooner we start, the more affordable it’s going to be for everybody,” said Justin Flagg, Krueger’s director of environmental policy. “When we get ourselves to that big shift in the makeup of the vehicle fleet and suddenly realize we have to transition all these buildings, we’re going to have to figure something out.”

In Colorado, state Rep. Alex Valdez, a Democrat, is crafting similar legislation that would require a certain percentage of parking spaces in new buildings to be wired for chargers. Valdez, who lives in a Denver high-rise building and drives an electric car, said the bill is informed by his own experience.

“I found out firsthand that these buildings weren’t built with the idea that down the road cars would be powered by electricity,” he said. “This is an opportunity to make sure that we’re doing it right going forward.”

But some mandates have drawn pushback in other states.

Missouri state Rep. Jim Murphy, a Republican, has proposed a bill that would block cities and counties from requiring their businesses or buildings to install charging stations. Murphy said St. Louis County’s mandate requires any business that wants to resurface its parking lot to spend thousands of dollars on charging stations. His bill would require that governments mandating chargers also provide funds to pay for them.

“There’s no feeling that we should stop the growth of EVs, that’s the future,” Murphy said. “But you can’t put it on the backs of small businesses and churches. If we’re going to make the little guy pay for it, I’m going to champion against it.”

Many states, including those that strongly promote electric vehicles, impose extra fees on the vehicles’ drivers, who don’t pay gasoline taxes. The fees are a way to ensure road funding stays intact as more drivers switch to electric. But electric vehicles advocates are wary of plans to adopt or increase those fees.

“We need to come up with really good policies to ensure we have the revenue to keep roads maintained,” said Geller with the Electric Vehicle Association. “But early in the [transition] process is not the time to impose such additional fees that only make a prospective purchaser think twice.”

Some states are exploring a vehicle-miles-traveled fee, which would charge drivers based on mileage rather than gas consumption. California expanded a pilot program on such fees last year. Other states, including Massachusetts and Minnesota, have bills pending that would create similar programs.

As states accelerate the pace of electric vehicle adoption, their gas tax revenues will start to dwindle, and lawmakers are still trying to determine how to replace that funding. The issue likely will take on greater urgency in future legislative sessions as the transition continues.

This story was originally published on Jan. 19 by THE CITY. Sign up here to get the latest stories from THE CITY delivered to you each morning.

For Tawanna Davis, winter means hauling out an electric space heater to keep warm when her Bronx building’s heat is insufficient.

Davis, 51, has for two decades been a resident of Twin Parks Tower North West in Fordham Heights, the site of a deadly fire earlier this month that officials have said was sparked by a malfunctioning space heater.

“You get the ice on the inside [of the window] and everything,” Davis told THE CITY. “It be really, really cold in your apartment.”

While some tenants said they’d be shivering without space heaters, others said they had to open their windows in the winter when their units became unbearably warm.

That hot-and-cold situation, which many New York apartment dwellers know all too well, highlights the importance of improving energy efficiency in residential buildings.

And this can be especially true for subsidized, income-restricted complexes — aka “affordable housing” — where improved comfort and safety are immediate benefits beyond slashed greenhouse gas emissions.

But upgrading affordable housing stock at the necessary pace presents logistical and financial challenges, which the administrations of New York City Mayor Eric Adams and Gov. Kathy Hochul need to solve regardless in order to achieve their climate goals.

The Twin Park Towers, built in 1972, are part of the state’s Mitchell-Lama housing program and receive some funding through the federal Section 8 program, which helps subsidize rents for low-income tenants.

“The fact that a relatively new building by New York standards has people living in situations requiring space heaters in order to reach a level of comfort suggests the complexity of this issue,” said Jonathan Meyers, a partner at HR&A Advisors, a firm that consults on real estate strategy and policy in New York and around the country.

“It’s a very stark reminder that there’s a fine line between inefficiency, which most of us can tolerate on a day-to-day basis, and tragedy, which is intolerable,” he added.

People working on the state’s decarbonization strategy, born out of New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act of 2019, say improvements in building energy efficiency aren’t just ways to mitigate climate change and get off of fossil fuels.

The green push, they say, can also lead to immediate health benefits: Properly insulating windows, for example, can ensure consistent temperatures in all seasons, and installing electric heat pumps can also help cool air. Both are useful to combat deadly extreme heat in the summer and illness-inducing chills in the winter.

“In terms of ever-increasing incidences of extreme-weather events, energy efficiency is going to play a bigger, maybe even life-saving, role,” said Eddie Bautista, director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance and part of the group that advises the state’s Climate Action Council.

On Tuesday, as if to further demonstrate the myriad dangers of fossil fuels, an apparent gas explosion rocked a residential building in Longwood, just a few miles south of Twin Parks. The blast killed one person and injured several others, officials said. Adjacent buildings were ruined in the ensuing fire, and the Fire Department is still investigating the exact cause.

The incident showcases the importance of phasing off gas and oil, not only to avoid carbon emissions, but to increase safety, environmental advocates note.

Gov. Kathy Hochul included in her budget plan this week a proposal to ban gas hookups in new buildings across the state by 2027, echoing a city law signed in recent weeks. Environmentalists say the governor’s timeline is not quick enough, and some asked for more funding to electrify existing housing.

“Thousands of New Yorkers are already dying premature deaths every year because of the fossil fuels we’re burning in our homes, and every once in a while, it’s not a slow, premature death thing — your house literally explodes,” said Alex Beauchamp, northeast regional director of the nonprofit Food and Water Watch. “We have to move much faster, not only for new buildings, but for existing ones as well.”

As part of the budget, Hochul also proposed a five-year, $25 billion housing plan that would in part cover efforts to weatherize and electrify New York’s housing stock. Her State of the State proposal earlier in the month cited projects to encourage electric, high-performance heating equipment and renovating buildings to keep temperatures consistent “to reduce the need for space heating and air conditioning,” among other reasons.

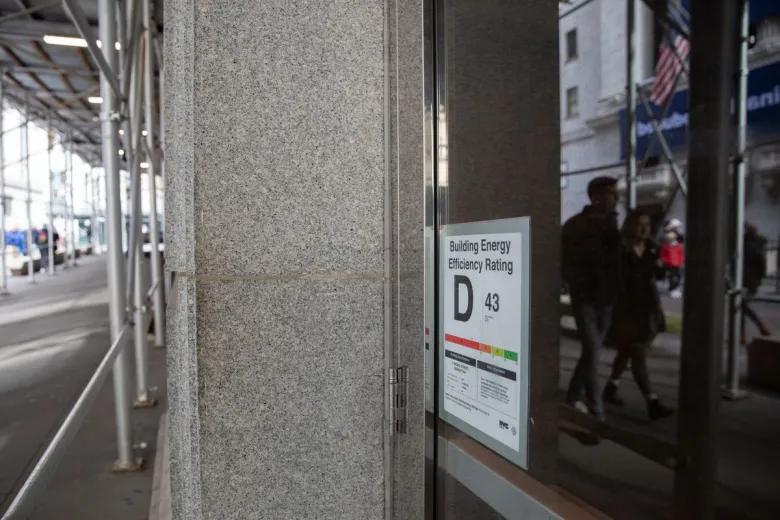

For over a decade, building owners in New York City have been required to tally their water and energy consumption data each year and submit the information to the city. Based on that, they get a grade. A 2019 law required landlords to make their efficiency grade public.

Twin Parks, for a second year in a row, earned a D in 2021, the same as about half of all buildings in the Bronx. Citywide, 39% of all buildings earned Ds.

The building, which installed new gas-powered boilers in 2015, according to city records, faces similar challenges to improving its efficiency as many other older buildings. Its residents, like many others in the city, don’t have separate thermostats to control indoor temperatures in their units.

They also don’t have individual electric meters, like many affordable housing buildings, meaning that they are not encouraged to use less power — so a resident can run a space heater all day and even open windows while doing so without thinking about the bill.

A spokesperson for the Twin Parks owners did not respond to requests for comment.

Landlords, who foot utility bills in the absence of what’s known as sub-metering, must themselves make improvements to reduce energy usage. Beyond money-saving potential, such capital upgrades focused on efficiency can result in healthier, more comfortable living quarters for residents.

Homes and Community Renewal, a state agency that develops and preserves affordable housing, considers energy efficiency for both new construction and preservation projects, a spokesperson said. It also requires private developers that work with the state to stick to efficient-design guidelines when applying for funding.

The problem lies in how to shore up enough funds to cover the scope of the efficiency-related work that must be done, while balancing the need to create and preserve affordable housing.

Housing dollars from the city, state and federal government are stretched “to the max,” said Lindsay Robbins, a senior advisor for building efficiency and decarbonization for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Many of the investments needed to improve existing subsidized affordable housing are identified when owners seek to refinance, which happens every 15 to 20 years, according to Robbin.

The city and state in 2017 developed an “integrated physical needs assessment” for properties, a tool which considers necessary capital improvements, like a roof replacement, along with an energy efficiency audit, among other measures.

“If we don’t make the most of that opportunity and ensure that building owners have resources and financing they need to really make these properties safe and healthy and efficient and electrified, that building’s probably not going to do diddly-squat for another 15 to 20 years,” Robbins said.

“We need to fundamentally rethink the kinds of public resources that we put into this … because putting people in quality and healthy housing — there’s nothing more important than that.”

Property owners can also apply for loans and grants through the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, and they may participate in a $24 million pilot run by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and HPD that seeks to finance electrification and energy efficiency upgrades in about 1,200 units of housing.

Another $30 million in state funds are available for income-restricted buildings that are seven stories or shorter through the RetrofitNY program.

Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-The Bronx) on Friday urged for the passage of federal legislation that would include about $150 billion for housing investments, which, he said, could be used to “create, preserve and retrofit 1.4 million units of affordable housing.”

“Part of Build Back Better must be building back safer,” he told reporters at the scene of the inferno earlier this month. “The fire in Twin Parks North West must be seen in the context of historical disinvestment from affordable housing, from places like the South Bronx, from lowest income communities of color, and the Build Back Better Act presents a historic opportunity to reverse decades of disinvestment.”

In addition to more federal funds, Robbins also wants to see more private financing, grants and investments from the New York Green Bank, a state agency with the mission to “accelerate clean energy deployment.”

The financing challenge will come to a head with new Local Law 97, which sets greenhouse gas emissions caps for buildings over 25,000 square feet. Mitchell-Lama buildings like Twin Parks have a compliance date of 2035, while most buildings must emit below the specified targets starting in 2024.

Now it’s up to Mayor Eric Adams’ administration — with the help of an advisory board — to finalize the rules that govern the new law and figure out how to help property owners finance the upgrades necessary to achieve the emissions caps.

In the meantime, state Attorney General Letitia James said she intends to use the power of her office “to get to the bottom of this fire” as environmental advocates continue to sound the alarm that energy efficiency equals safety and justice.

“We can’t achieve a climate just society without centering BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and People of Color] and low-income communities,” said Daphany Sanchez, executive director of Kinetic Communities Consulting, a firm focusing on energy equity. “The fire that you saw in The Bronx is exactly the issue: the result of people ignoring climate, the result of people ignoring Black and brown communities.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news organization dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York

This article is co-published by the Energy News Network and Planet Detroit with support from the Race and Justice Reporting Initiative at the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University.

It’s that time of the year for reflection, whether personally or, in James Gignac’s case, on the progress Midwest states have made in pursuing clean energy goals.

Gignac is the Senior Midwest Analyst for the Climate & Energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. He shared with Planet Detroit some additional thoughts from his recent post about milestones reached by Michigan and its neighbors.

Q: Consumers Energy has a proposed plan that will come up for approval before the Michigan Public Service Commission in 2022. That plan includes burning natural gas. How can the MPSC hold utilities accountable for those proposed actions?

A: The utilities in Michigan, including Consumers Energy, are obligated to display ways to provide the lowest cost, cleanest and reliable energy for their consumers in the state using an Integrated Resource Plan.

While Consumers Energy has some really good features in their pending plan, including phasing out all of the coal plants by 2025 and making large investments in solar, there’s also the question of the role of methane gas, which is sometimes called natural gas.

The question is, what is the role of gas in their future resource plan? What Consumers Energy is trying to do is begin to map out how it will achieve the carbon reduction goals that it as a company has established.

While they’re not proposing to build new gas plants, they’re proposing to acquire existing gas plants. And what we and other advocates are concerned about is the transition away from coal and towards clean energy. Investing in gas resources is risky for customers because those gas plants could very quickly become uneconomic or unneeded.

And so while it’s good that the company is not wanting to build a new gas plant – which most utilities are moving away from, it’s still concerning from an economic perspective and because they still produce carbon emissions and other pollutants.

One of the facilities in particular concerns environmental justice advocates. Testimony submitted by our stakeholder coalition and others, highlights the environmental justice concerns of existing natural gas plants.

Q: What other items should we watch out for in Michigan in 2022 you’d like to highlight?

A: In 2021, especially in Michigan, we saw the increasing interest in demand from communities and customers to have greater control and greater amounts of locally-owned clean energy resources. We’re beginning to move away from the traditional model of utilities providing electricity to customers from faraway power plants.

DTE Energy will be filing an Integrated Resource Plan in the Fall of 2022, which is a year earlier than planned. The upside of that is that we will have a chance to look at DTE’s newest proposals a year earlier than expected. That’s important because we need to be moving quickly, and we need to urge utilities to continue taking rapid steps in a clean energy transition.

So looking ahead to 2022, the DTE Integrated Resource Plan and the important opportunity to review those current plans.

I’m also looking forward to seeing a strong action plan from the Council on Climate Solutions. Last year, Governor Whitmer’s executive order, the Council on Climate Solutions, has been working to develop an action plan to reach the state’s carbon reduction goals. We’ll see that quickly in 2022 as a draft will be released in mid-January, and the Council will then finalize that in February and March.

We’re hopeful that the document will be a strong plan for Michigan and include immediate and near-term steps that can be taken and lay out a long-term action plan for additional policies that can be put in place.

We also will have a Consumers Energy decision on its Integrated Resource Plan. So we’re hopeful that the Public Service Commission will approve the company’s plans to retire its coal plants and pursue its solar expansion. And ideally, either postpone or not approve all of the existing gas plants for acquisitions. So if there’s an opportunity to evaluate those further or ask the company to do some additional analysis to ensure cleaner energy options could be pursued instead of those gas plants.

And in Michigan’s legislature, I think it’s important to continue focusing on and discussing clean energy legislative proposals and to build the demand for taking action at the legislative level.

Q: There was a recent major win for Illinois – anything you want to share about it?

A: The Climate and Equitable Jobs Act (CEJA) was based on building upon and expanding previous legislation, so in 2017, Illinois passed the Future Energy Jobs Act. What advocates started doing immediately after that legislation passed was starting to think about the next set of policies that can be passed in Illinois, while identifying things that needed to be improved or changed from the 2017 legislation.

CEJA was the product of many conversations and discussions amongst a broad set of stakeholders, which led to its passing in 2021.

Centering the needs of lower-income communities and making sure that clean energy investments and benefits are shared amongst all Illinois communities is a key to making them a leading national leader in the equitable pursuit of clean energy and climate action.

Q: What else should Michigan consider in 2022 related to clean energy advocacy and policymaking?

A: I would say that crafting clean energy policies centering people and lower-income, traditionally disadvantaged communities. Doing that is important, but it’s also popular. People want to see equity being a key part of clean energy and climate responses.

So I think our work in 2021 really highlighted that and we have an increasing amount of good examples to draw from, whether it’s Illinois’ efforts or programs in other states that can be applied in Michigan and elsewhere.

Q: What’s next for UCS?

A: We’re looking to follow up on our Let Communities Choose Report in partnership with Soulardarity. In Highland Park, we’re working on analyzing a microgrid for the Parker Village neighborhood in Highland Park. So that would be an additional piece showing the potential for local clean energy.

We partner with many other groups doing great work in Michigan and at the state level, advocating the Council on Climate Solutions and the Michigan Public Service Commission.

Shuttered during the pandemic, the historic Strand Theatre in Pontiac, Michigan, faced an uncertain future. But previous energy efficiency investments provided a lifeline.

The Strand was able to use C-PACE — commercial property-assessed clean energy financing — to retroactively fund and refinance those investments, essentially rolling the cost into their property taxes to be paid over time and freeing up cash for them to wait out the pandemic.

While the pandemic and worker and supply chain shortages have made the last two years rough across countless sectors, Michigan’s C-PACE program nonetheless enjoyed its best two years ever in 2020 and 2021, with 28 projects closed including the Strand.

This year at least five local jurisdictions in Michigan saw their first-ever C-PACE project, and four more are expected to do so this year or in early 2022. That’s according to Todd Williams, president and general counsel for Lean & Green Michigan, the company that administers C-PACE in the state, and recent winner of the Michigan Energy Innovation Business Council’s Business of the Year Award.

“PACE was a form of rescue capital for [the Strand]. It allowed them to refinance some loans, delay some payments, maintain the business through hopefully the end of the pandemic,” Williams said. “It was like a second mortgage on your house. You’ve already completed the projects, they’ve already been funded, and this is a method in which they were able to draw some capital back out. It was not necessarily a large project, but without it, it’s completely possible an asset in that community would have closed.”

As the Strand’s experience shows, C-PACE can be a tool not only to install solar or make energy efficiency improvements, but to provide financing in general, since it can free up capital immediately that businesses might otherwise have used on investments that qualify as clean energy or resiliency-related. This potential may be even more attractive in uncertain and rocky economic times like the current moment.

“Commercial PACE can be your financing tool to fill a financing gap and meet energy efficiency goals at the same time,” said Cliff Kellogg, executive director of the C-PACE Alliance, at a panel during the Urban Land Institute’s annual conference in Chicago in October.

Mansoor Ghori, co-founder and CEO of Petros PACE Finance, said during the panel that since many businesses didn’t know how long the economic uncertainty and recession caused by the pandemic would last, they “refinanced their equity using PACE, and used that money to make sure they had enough capital to get through however long it would take.”