Vermont Gas Systems is offering to install electric heat pumps in their customers’ homes, the latest example of how state policy is nudging the utility to adapt its business model.

In order to comply with the state’s climate mandates, the utility is building a broader portfolio of thermal systems that will help both the business and its customers make the transition to a decarbonized future, said Richard Donnelly, the company’s director of energy innovation.

“We offer natural gas, energy-efficient products, weatherization, renewable natural gas, heat pump water heaters, and now heat pumps,” he said.

Expanding its offerings also puts the company in a good position to comply with the state’s new Clean Heat Standard, which became law last week after the legislature overrode a veto by Republican Gov. Phil Scott. Once implemented in 2025, the law will require fuel dealers to reduce the amount of fossil fuel they sell over time, or earn “clean heat credits” by doing things that offset building emissions, such as weatherization services and installing heat pumps.

Under the new heat pump program launched this month, the state’s only natural gas utility will use its in-house service technicians to install centrally ducted, cold-climate heat pumps in qualifying homes. The highly efficient systems use electricity, rather than fossil fuels, to heat and cool homes.

Customers will be able to either buy or lease the systems at rates that factor in the heat pump rebates available through the state’s utilities in partnership with Efficiency Vermont.

“We’ll process that rebate up front for a purchase, and bake it into our lease prices as well,” Donnelly said.

Each system will use the home’s existing ductwork, and be integrated with the homeowner’s gas furnace, which will serve as a backup heating source during extremely cold weather. A smart thermostat will automatically switch back and forth between the heating sources according to the customer’s settings.

“We are offering our customers an opportunity to diversify their heating system, adding in the benefits of resiliency,” Donnelly said. “This is also an opportunity to reduce their carbon footprint.”

In order to qualify, homes must already have ductwork that delivers heat through vents. They must also have a fairly efficient furnace.

An estimated 14,000 of the utility’s 55,000 customers could be eligible. Most homes in the company’s service area have hydronic heating systems with radiators or baseboard radiators; Donnelly said the company will begin offering heat pump solutions for those customers in the future.

The new program comes just over a year after Vermont Gas announced it would begin installing electric heat pump water heaters for its customers. The company is also looking for a site to test its first fossil fuel-free networked geothermal project, another possible business to branch into as the state moves away from fossil fuels.

“As a distribution utility, energy efficiency utility, and integrated energy services provider, Vermont Gas is uniquely positioned to help its customers take advantage of the latest and most cost-effective technology,” said Dylan Giambatista, the company’s public affairs director.

Vermont’s climate mandates call for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 26% from 2005 levels by 2025, 40% from 1990 levels by 2030, and 80% by 2050.

“We are going to need a lot of different partners” to meet those goals, said Johanna Miller, energy and climate program director for the Vermont Natural Resources Council. “To the degree that our utilities like Vermont Gas will lean into and help their customers cut costs and cut carbon, I think that that is important.”

Gas heating customers switching to electric heat pumps won’t necessarily save money, at least for now. While the heat pumps are more efficient, gas is currently the cheaper source for heating, Donnelly said.

But the company is developing an online calculator that will allow customers to see how setting the system to swap over to the furnace at 20 degrees versus, say, 25 degrees will compare in terms of carbon reduction and heating costs. They will also be able to measure the carbon and cost impact of adding in renewable natural gas.

“A lot of our customers are motivated by carbon reduction, but they don’t know how much a heat pump would help in terms of their overall consumption,” Donnelly said. “We’re taking that role to educate.”

Giambatista said he installed a heat pump in his 1945 house last fall. He set the smart thermometer to swap over to his gas furnace when temperatures dropped to 25 degrees. Over the winter his gas usage dropped by about 60% compared to previous years, he said.

To date, about 45,000 ducted and ductless heat pumps have been installed in Vermont under the state’s rebate program, according to Phil Bickel, HVAC and refrigeration program manager at Efficiency Vermont.

They are primarily in homes that heat with fuel oil, the majority of homes in the state.

“We’ve seen the cost of all fossil fuels go up and down over the years,” Bickel said. “The main thing about making the switch to heat pumps is it provides a little bit more of a stable cost. They are three times more efficient than oil or propane, and they also provide the low carbon benefit, as well as the cooling benefit.”

Efficiency Vermont does recommend that homeowners maintain a backup source for heat. The heat pumps work well down to about -15 degrees, “but in Vermont, there are those times when we are going to have a long cold snap,” Bickel said.

A small but growing number of Minnesota electricians are finding steady work installing residential electric vehicle chargers.

Minnesota has around 35,000 electric vehicles on the road today, but that number is expected to rapidly grow in the coming years as more models become available. The state is using federal funds to help build out a public charging network along major highways, but even so, research suggests most drivers are likely to mostly charge at home.

Some will simply have to plug into an existing outlet in their garage, but many will need electrical upgrades, especially those with older homes or those who want to take advantage of faster charging times. Participating in certain utility programs may also require the installation of new equipment.

That’s creating an opportunity for electricians like Adam Wortman of St. Paul, who installed an electric vehicle charger at the home of a clean energy advocate four years ago and has since retooled his business to focus almost solely on similar projects.

“It’s where I see the demand,” Wortman said, “and from a business standpoint, it’s nice to have a specialty,”

It’s unclear exactly how many electricians have decided on a similar path, but anecdotally it’s more than a few. The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 292 has trained and certified more than 400 electricians over the past two years to install commercial electric vehicle chargers along state and federal highways, but residential installations are more commonly non-union contractors.

“What I’ve seen is that with more electric cars and with more of the demand for electric car chargers, a lot of these smaller shops seem to be picking up work,” said Andy Snope, business representative and legislative and political director for IBEW Local 292. “They are getting a niche and a reputation.”

The market for electricians installing vehicle chargers is bifurcated into commercial and residential projects. He and others estimated that dozens of electrical firms install chargers, but just a handful focus primarily on chargers. Firms attract jobs through word-of-mouth advertising and references from vehicle manufacturers or utilities such as Xcel Energy.

“It seems like kind of an underworld niche for electrical contractors who are usually smaller but are getting a lot of this work, which is great for a small business,” he said.

Paul Hanson, energy service sales representative for Connexus Energy, said the cooperative recommends that customers getting vehicle chargers reach out to Wortman and a handful of other contractors who specialize in installations and have had good reviews over the years. Hanson said he’s started hearing from solar and heating and cooling companies that want to get on the utility’s list of preferred charging installers.

“Everyone is trying to get their hand into the electric vehicle market,” Hanson said, adding that Connexus saw a 90% increase from 2021 to 2022 in members enrolled in its off-peak vehicle charging program.

Electricians working on vehicle chargers generally gain their first experience working with Tesla, which had the first electric vehicles on the market. Many electricians bought Teslas early and discovered other buyers were struggling with firms that knew anything about chargers.

Bryan Hayes, founder and owner of Bakken Electric LLC, bought a Tesla in 2012 and moved from providing general residential electrical services to installing vehicle chargers. Though Hayes had been an electrician for two decades, he wanted a change.

“My reason for doing it was more ideological,” he said. “I wanted to do something that leaves a legacy of making the world a little better place than I found it.”

Hayes built a staff of six electricians who have installed over 4,000 chargers in the Twin Cities region, ranging from garages to apartment buildings to downtown Minneapolis ramps. His projects come from recommendations from electric vehicle manufacturers and word-of-mouth advertising.

One area of growth has been installing chargers in multifamily buildings. Hayes created a separate company, U.S. Charging, to partner with Tesla to install its commercial chargers in multifamily buildings. “Condominiums and apartments [and] hotels are now a big focus of my business,” he said.

St. Paul-based Sherman Electric owner Jim Sherman has installed thousands of vehicle chargers and collaborated with Xcel Energy on its Accelerate at Home charging program several years ago. Installations represent 40% of his business, with working at restaurants a second specialty.

“I think the market is getting more specialized and more niche than ever,” Sherman said. “I know contractors that only work on hospitals, and I know contractors that only do apartment buildings.”

Part of the specialization comes from building codes that have become stricter and more demanding. Sherman and his staff of four assistants developed expertise and an understanding of building codes by concentrating on vehicle charging and a handful of other industry sectors, primarily restaurants.

The charging sector is new enough that inspectors often call Sherman with questions and situations they encounter. Homeowners who suffered poor installations pay him to correct the mistakes.

The biggest challenge lately has not been codes or charger technology but instead educating newer EV customers. The early electric vehicle buyers had few questions because they had done their homework and understood the technology.

“My average phone call now is about 20 minutes to sell a customer because I have to educate them about how [the charger] works, how the cars work, how the cars charge, how the power works — everything,” Sherman said. “The early adopters, the Tesla people, knew their stuff. Now it’s getting to be a wider, broader range of people driving electric vehicles.”

In the Twin Cities, home and multifamily building owners typically pay $2,000 to $3,000 to install a Level 2 charger, which provides from 20 to 50 miles per charging hour. Level 1 charging, in contrast, requires a common outlet and no electric system upgrade but charges vehicles at just two to five miles per hour.

Wortman said Level 2 chargers can require homeowners with attached garages to add another circuit to their electric panels. He installs a separate meter for detached garages and usually upgrades the building to a 240-volt system. Then, typically, he has the homeowner pay Xcel or their utility to drop a line from its transmission grid to power detached garages.

While there’s no average day for Wortman, he usually has two to three installations lined up. Many times, he and other electricians will pick up small jobs like changing out or adding plugs or other repairs in addition to installing chargers.

Clients say electricians are hard to schedule for smaller jobs and are happy to pay them to do extra work, he said. He and other electricians also consult with clients on federal tax and utility rebates they can use to reduce their costs.

Multifamily apartments and condos present different obstacles. Electricians sometimes must connect chargers to the electric systems of clients living several floors above the garage. Or they work on managed charging that moves electricity around to different cars, a common solution to serve the growing number of EV drivers living in apartments and condominiums.

Hayes has directed much of his business to working with multifamily clients and Wortman and other electricians see it as the next frontier.

This article was originally published by Maine Monitor.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the tax relief for heat pumps and other home energy saving projects that is available under the Inflation Reduction Act. One aspect of the IRA incentives is a rebate for heat pumps and other home electrification projects that is still being finalized by the state. The story also misstated a rebate available for small scale home sealing and other do-it-yourself projects. That rebate has expired.

Venus Nappi strolled through a community center in South Portland in early April, chatting with vendors at Maine’s annual Green Home + Energy Show about electric heat pumps, solar power, and the discounts that aim to make these and other technologies affordable. A worker in an oversized plush heat pump costume waved a gloved hand nearby.

Nappi heats her Gorham home with oil, as do 60% of Mainers — more than any other state, as The Maine Monitor reported in the first part of this series. She finds oil to be dirty, inconvenient and expensive. Her oil costs this winter, she said, were “crazy, absolutely right up through the roof.”

Nappi joined a record-breaking crowd at this expo because she’s ready to switch to heat pumps, which can provide heating or cooling at two or three times the efficiency of electric baseboards and with 60% lower carbon emissions than oil, according to Efficiency Maine.

“It’s good to have incentive to try to go somewhere else rather than just the oil,” Nappi said. “Even gas, propane, is actually a little expensive right now, too. The heat pumps are kind of in the middle.”

Government rebates of up to $2,400, with new tax breaks coming soon, help with up-front heat pump installation costs that can range above $10,000. These incentives have helped put Maine more than 80% of the way to its 2019 goal — now a centerpiece of the state climate plan — of installing 100,000 new heat pumps in homes by 2025, and many more in the years after that.

“This is a real highlight of our climate action,” said state Climate Council chair Hannah Pingree. The state aims to have 130,000 homes using one or two heat pumps by 2030 and 115,000 more using “whole-home” heat pump systems, meaning the devices are their primary heating source.

But Maine lags much further behind on a related goal of getting 15,000 heat pumps into low-income homes by 2025, using rebates from MaineHousing. At the end of last year, it had provided just over 5,000 heat pumps to the lowest-income homes.

These homes face particular barriers to maximizing the benefits from this switch — from poor weatherization, to navigating a daunting web of incentives, to fine-tuning a blend of heat sources that can withstand power outages and actually save money instead of driving up bills.

As fossil fuel costs remain high, the pressure is on for advocates and service providers to expand access to heat pumps and other strategies for reducing oil use, especially for people most often left out of the push for climate solutions.

In Maine and beyond, it’s clear that heat pumps are having a major moment — heralded in national headlines as a crucial climate solution that successfully weathered a historic cold snap.

But the technology is not new. It’s long been used in refrigerators and air conditioners.

“The problem was, when you design a heat pump to primarily provide cooling … it is not optimized for making heat,” said Efficiency Maine executive director Michael Stoddard. “So everyone concluded these things are no good in the winter. And then around (the) 2010, ’11, ’12 timeframe, the manufacturers started introducing a new generation of heat pumps that were specially designed to perform in cold climates. … It was like a switch had been flipped.”

Maine has offered rebates for heat pumps ever since this cold climate technology emerged. Even former Gov. Paul LePage, a Republican who frequently opposed renewable energy and questioned climate science, installed them in the governor’s mansion and told The Portland Press Herald in 2014 that they’d been “phenomenal” at replacing oil during a cold snap.

Heat pumps provide warmth in cold weather the same way they keep warmth out of a fridge — by using electricity and refrigerants to capture, condense and pump that heat from somewhere cold to somewhere warmer. Simply put, they squeeze the heat out of the cold air, then distribute it into the home.

The current generation of heat pumps will keep warming your home even if it’s around negative 13 degrees out.

Heat pumps are less efficient in these colder temperatures, requiring more electricity to make the same heat. With outdoor temperatures in the 40s and 50s, today’s typical cold-climate heat pumps can be roughly 300 or 400% efficient — tripling or quadrupling your energy input.

As temperatures drop into the teens, heat pumps are often about 200% efficient. And in the single digits or low negatives, heat pumps can be closer to the 100% efficiency of an electric baseboard heater. Costs at this level are closer to that of oil heat, which usually has about an 87% efficiency rating.

This means heat pumps often generate the most savings and are most efficient when temperatures are above freezing, or when used to provide air conditioning in the summer — something Mainers will want increasingly as climate change creates new extreme heat risks.

“During the shoulder seasons, you can definitely use a heat pump. When it’s wicked cold out, then you’d probably turn on your backup fuel. That’s not the official line of Efficiency Maine Trust, but a physical and engineering reality,” said energy attorney Dave Littell, a former top Maine environment and utilities regulator whose clients now include Versant Power — which, along with Central Maine Power, now offers seasonal discounts for heat pump users.

This is a relatively common approach among installers, such as ReVision Energy, a New England solar company that also sells heat pumps. They don’t recommend heat pumps as the only heating source for most customers, especially those who live farther north, unless the home can have multiple units, excellent insulation, and potentially a generator or battery in case of a power outage — a costly package overall.

“(Heat pumps) do still put out heat (in sub-zero weather), but less, obviously, and they have a lot more cold to combat in those conditions,” said Dan Weeks, ReVision’s vice president for business development. “Generally … we do recommend having a backup heating source.”

These blends of heating sources are nothing new in Maine — many families combine, say, a wood stove with secondary heat sources that rely on propane, oil or electricity. Experts say heat pumps are a powerful addition in many cases, adding flexibility and convenience.

Heat pumps will add to your electric bills but also reduce another expense that’s eating up a lot of household budgets — heating oil. Instead of spending hundreds to fill your tank just as winter starts to wane (a full 275-gallon tank would run more than $1,000 right now), you might be able to switch entirely to your heat pump in early spring. Vendors say a heat pump will be much more cost-effective than fossil fuels for the vast majority of Maine’s heating season.

One study from Minnesota — which has lower electric rates and more access to gas, but has made a similar push for heat pumps — found the greatest savings from using a heat pump for 87% of the heating season, switching to a propane furnace only below 15 degrees.

Electricity costs also change less frequently than fossil fuel prices. And the advent of large-scale renewable energy projects, like offshore wind, aims to help smooth over rate hikes that are now driven by the regional electric grid’s dependence on natural gas, said Littell of Versant Power. (While Maine has little gas distribution for home heat, New England power plants use a lot of it to make the electricity that’s primarily imported to Maine on transmission lines.)

This will also mean the electricity that fuels your heat pump will be even lower-emissions than it is now. The emissions comparison between heat pumps and oil is based on the current New England electric grid’s carbon footprint, which is set to continue shrinking.

Paige Atkinson, an Island Institute Fellow working on energy resilience in Eastport, pitches heat pumps as a good addition to a home fuel mix. But she said all these cost comparisons can cause anxiety for people unsure about switching. Oil costs, though rising and prone to fluctuations, can be a “devil you know” versus heat pumps, she said.

“Transitioning to an entirely new source of heat creates a lot of ‘what-ifs,’ ” she said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty about how to best use that system — will it meet my needs?”

The best way to guarantee savings from a heat pump is likely to work closely with your contractor about where to install it, and when and how to run each part of your home’s fuel mix.

“Our job is to educate (customers) on proper design, proper sizing, best practices for installation,” said Royal River Heat Pumps owner Scott Libby at the South Portland expo. “I always tell people to use the heat pump as much as possible. … If you are starting to get chilly, that might just be for a couple hours in the morning when the temperature outside is coldest, so maybe use your fossil fuels just to give the system a boost in the morning, for even an hour.”

The condition of your house is another big factor in the heat pump’s performance.

“Weatherization is a great tool. It is not necessary to make a heat pump work … but the heat pump will work better if the house is well weatherized,” said Stoddard with Efficiency Maine. “When you have those super, super cold days, it won’t have to work as much.”

The need, ideally, for updated insulation and air sealing as prerequisites for heat pumps may help explain the slower progress on getting them into low-income homes. (We’ll address heat pumps as a potential benefit for renters later in this series.)

“I think a lot of the homes especially that (qualify for rebates from) MaineHousing … require a lot of upgrades, just sort of basic home improvements, to get to the next step,” said Hannah Pingree of the state Climate Council.

Bob Moody lives in the kind of house Pingree is talking about in Castle Hill, a tiny town just outside Presque Isle. The ramshackle clapboard split-level totals four stories, set into a wooded hillside. Moody grew up down the road, and his family built this place in the 1980s using much older scrap materials from the former Loring Air Force Base in Caribou.

On a snowy day in March, Moody was visited by a small team from Aroostook County Action Program, or ACAP. It included his next-door neighbor, ACAP energy and housing program manager Melissa Runshe. She and her colleagues were there for an energy audit, a precursor to weatherization projects — all paid with public funds through MaineHousing.

“Weatherization is at the very top. If your heat isn’t flying out of your house, it’s going to save you money,” Runshe said. “We have a lot more winter here (in Aroostook County) than in the rest of Maine, so it’s really important to make sure that the houses are energy-efficient — so that they’re not burning as much oil, so that they’re not spending as much money on oil.”

ACAP officials said they don’t push any technology over another when meeting new clients, but instead describe the options and benefits — savings, comfort, a smaller carbon footprint. This all typically happens after someone has called for heating aid or an emergency fuel delivery — or, in Moody’s case, an emergency fix for their heating equipment.

Moody’s health forced him to retire early, and he now lives alone on a low fixed income. He’s gotten energy assistance and upgrades from other state and county programs before, but first called ACAP late last year when his main heat source, a kerosene furnace, suddenly died. ACAP got him a new, more efficient oil furnace, then signed him up for a weatherization audit.

“If it hadn’t been for assistance, I would have been really in trouble,” Moody said as he filled out paperwork at his kitchen table. A sticker on the wall proclaimed Murphy’s Law — anything that can go wrong, will. “Murphy has been settling in very heavily on me,” he laughed.

Moody’s ACAP audit included a blower door test, which depressurizes the house to expose air leaks. They showed up on a thermal imager as cold seeping in through window seams, power outlets, hairline cracks in the walls, and most of all, an uninsulated exterior-facing wooden door that was down the hall from Moody’s new furnace, sucking heat from the rest of the house.

“He has, roughly, a (total of a) one-by-two-foot-square hole that’s wide open in the house,” said energy auditor BJ Estey. “It’s basically like the equivalent of having a window open year-round.”

The inspection showed weatherization could save Moody $1,230 a year on oil. New windows and doors would help even more — but the weatherization program doesn’t offer those, and there’s a 900-person waiting list for ACAP’s program that does. Instead, the staff told Moody to try a federal option for home repair grants and loans, and promised to help him with the forms.

For people who don’t receive MaineHousing-funded upgrades, Efficiency Maine offers healthy rebates for air sealing and insulation performed by contractors. Last winter it also added a small new rebate for do-it-yourself home weatherization, such as plastic wrap for windows, pipe wraps and caulk, which has since expired.

Groups like ACAP also offer free heat pumps for low-income residents using MaineHousing funds. The rebates feed the state’s goal, where progress has been slow.

Moody has one kind of heat pump in his home but it’s not the type that provides hot air — it’s a heat pump-based hot water heater, which he got for free through a rebate from Efficiency Maine. He loves the savings and convenience it’s provided.

But he doesn’t think an air-source heat pump — the kind that can replace an oil furnace — will work for his home, which has many small rooms split up across levels. (Installers often recommend at least one heat pump per floor.) He’s also worried about how a heat pump would affect his electric bills. He knows he couldn’t afford electric baseboard heat, so he’s concerned about the very cold conditions where a heat pump’s efficiency drops down to around that level.

“Sometimes in the middle of the winter, you get so cold that you just might as well have an electric (baseboard) heater,” he said. “And there ain’t no way that I can afford an electric heater — not even one month.”

Down the road in Castle Hill, Melissa Runshe’s newer-construction house came with three heat pumps, a boiler that can use wood pellets or oil, and a propane fireplace. “I think (heat pumps) are wonderful,” for heating when temperatures are above about 20 and for summer cooling, she said. “They definitely offset the cost of my oil.”

While not every house is heat pump-ready, it may be even more important to get folks like Moody connected with this energy safety net in the first place. This will continue to decrease his oil dependence, offering escalating upgrades as his home changes and funding sources shift.

“In the social services world, there’s this idea of ‘no wrong doors,’ and we need to adopt that for home energy as well,” said Maine Conservation Voters policy director Kathleen Meil, the co-chair of state Climate Council’s buildings group. “There’s no distilling and simplifying how people live in their homes. You experience your house and your home’s heating situation not as a data point, but as your daily life.”

For people like Meil, there are multiple goals working in tandem — help Mainers reduce their reliance on planet-warming fuels like heating oil, while helping them lower household energy costs, and live with more comfort and convenience. This is what climate advocates mean when they say the crisis is “intersectional” — it’s interwoven with health, race, poverty and more.

Juggling these issues can mean making more incremental progress toward emissions goals — but that’s far better than nothing in scientific terms, said Ivan Fernandez, a professor in the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute.

“Everything we do, every increment we do, counts,” Fernandez said. “I think we need to do this transition in a relatively quick way, recognizing that it will be imperfect, and spending a good part of our focus on realistic, data-driven, science-driven tracking of where we are at, so we’re not telling ourselves fables that aren’t substantiated by the science.”

Officials say Maine used this kind of science in building detailed goals for things like heat pump adoption, adding them up toward a path to the two biggest targets that are inked in state statute — reducing emissions 45% over 1990 levels by 2030 and 80% by 2050.

“Ultimately the atmosphere will determine how successful we are. It’s already telling us that we have not been very successful in many ways,” said Fernandez. “But … I think we’re embracing the reality of that a lot better.”

Setting these goals carefully and pushing hard to meet them does not guarantee equity — and there are still holes in the state’s approach, according to people working on spreading the benefits of the energy transition to those who might not be able to access it without help.

The Community Resilience Partnership, or CRP, is the state’s signature grant program for town-level climate action. Each project starts with a local survey to determine residents’ priorities out of a 72-item list that includes everything from flood protection to energy efficiency.

State officials say the CRP was designed primarily to build up towns’ capacity to respond to climate change. But advocates say they’ve had to work around a crucial gap in the program: It won’t buy equipment directly for individuals, which is often what people say they want the most.

“There are communities who really do have the need to fund heat pumps beyond what Efficiency Maine is providing,” said Sharon Klein, an energy consultant and University of Maine professor who works with Maine tribes on their CRP projects. “Because there’s still that last piece of it where money still needs to be put up, and some people don’t have that money.”

For people whose income is not quite low enough to qualify for a totally free heat pump through MaineHousing, Efficiency Maine’s rebates will cover $2,000 for a first unit and $400 for a second. People at any income level can get $400 to $1,200 for one or two units. This might cover some or all of the cost of a typical single heat pump — but total installation costs can range from around $4,000 to above $10,000, depending on the complexity of the system.

Starting this tax year, the Inflation Reduction Act will offer new tax credits of 30% for heat pumps, up to $2,000 per year. The IRA will also provide additional rebates to cover heat pumps and other home electrification projects, but the details of those rebates are still being finalized. The IRA allows states to, in theory, offer as much as 100% of project costs up to $8,000 for low-income families, or 50% of costs for moderate-income families — but state officials are still deciding how exactly this limited pot of money will be used and who will be eligible. The rebates will not be universal or unlimited, said Stoddard with Efficiency Maine, but should benefit several thousand homes.

Dan Weeks of ReVision Energy said increasing availability of low- or no-interest loans is another priority for those who want to see more people switch from oil to efficient electric heat. The IRA will help Maine expand its Green Bank in the next year or so to “start offering financing to particularly low-income folks and folks with poor credit,” Weeks said.

But tax credits and cheap loans are still deferred ways of helping people lower their oil costs and cover those remaining heat pump costs. Downeast CRP coordinator Tanya Rucosky, who works on community resilience for Washington County’s Sunrise County Economic Council, said many families simply can’t afford to make the switch.

“Folks need just a little bit of seed money,” she said. Without more support, “it locks out the people that potentially need it the most.”

Atkinson, the Island Institute Fellow, said Eastport found a creative way to offer direct funding within the constraints of its CRP grant. People who participate in the city’s peer-to-peer energy coaching program, Weatherize Eastport, can get another $2,000 toward heat pump installation.

“They’re agreeing to become almost ambassadors for this program. One of the steps to do that is to volunteer some time,” Atkinson said. “The city is compensating these residents for their time involved in this partnership, rather than saying, we will just give you funds for X, Y and Z.”

Solutions like this are key to ensuring these tools for moving off oil can grow equitably, said Rucosky — helping more people to join the transition and spread the gospel of its benefits.

“Especially for Mainers — they’re so salty and smart. They’re like, ‘What’s the catch?’ So I don’t think there’s any getting around the labor of it,” Rucosky said. “The more people have successful experiences doing this, the more I don’t have to be the one saying it …and it can be like, Bob down the road. And so it builds — but it takes a long time to build that, where everybody knows this is how you get this done. That’s going to be years in the making.”

New electric vehicle rebates are expected to become available in Massachusetts in early summer, some nine months after lawmakers passed a bill calling for the incentives’ immediate implementation.

The state has said funding and logistical obstacles have delayed the launch of the new provisions, which will add higher incentives for low-income car buyers, create a rebate for the purchase of used electric vehicles, and establish a system for providing rebates at the point of sale, lowering the upfront cost of the vehicle.

Advocates have been understanding of the complications with rolling out these provisions but are eager for the new components to take effect.

“I am sympathetic, but if we want to hit not our climate goals — our climate requirements — we really need these coming online as soon as possible,” said Kyle Murray, Massachusetts program director at climate nonprofit the Acadia Center.

Massachusetts has ambitious goals for reducing its transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions. The state’s clean energy and climate plan sets a goal of slashing vehicle emissions by 86% from 1990 levels by 2050. One of the major strategies for getting there is increased adoption of electric vehicles: The plan calls for all new vehicles sold in the state to be electric by 2035. The state has also set a target of having 900,000 electric vehicles on the road by 2030.

To those ends, the state’s electric vehicle incentives have long been considered among the best in the country. The Massachusetts Offers Rebates for Electric Vehicles program, or MOR-EV, was launched in 2014, providing rebates of $2,500 on eligible purchases or leases. For a time the rebates dropped to $1,500 due to funding issues, before returning to their original level in 2020.

The climate law passed in 2022 called for expanding these incentives in several ways. The base rebate was increased to $3,500 and the price cap for eligible vehicles was raised to $55,000, changes that have already been implemented. Other changes have been more difficult to put into effect.

Though the law authorizing the program was passed in August 2022, the legislature didn’t provide any additional funding until November.

“The administration was a bit handcuffed in that they couldn’t set up a program they weren’t sure they’d have the money for,” Murray said.

At the same time, implementing the new provisions required enough updates to the program software that the state had to put out a call for proposals from vendors to handle the changes. In March, the state chose to continue working with the existing vendor, the Center for Sustainable Energy, and the final program design is now underway with the first components rolling out this summer, according to information from the state Department of Energy Resources.

“I am hoping for a July 1 roll-out of all the new features the program requires to satisfy legislative intent,” said state Sen. Michael Barrett, a champion of the 2022 climate bill.

A new rebate will provide an additional $1,500 to low-income residents who buy or lease a qualifying vehicle, though the state is still determining details including what income levels will be eligible and how income will be verified. A used vehicle rebate and an enhanced rebate for consumers trading in a vehicle with an internal combustion engine are also expected this summer, though, again, details have not yet been released.

While advocates have generally expressed understanding for the lengthy implementation process, this lingering uncertainty has also frustrated some.

“That lack of specificity makes it really hard to help people figure out what car to buy when,” said Anna Vanderspek, electric vehicle program manager for the Green Energy Consumers Alliance. “Overall, we wish they would have moved faster and been clearer about which changes would occur when.”

A major uncertainty that remains is whether the new provisions will be effective retroactively, considering the delays in implementation. Barrett is a strong proponent of retroactive rebates.

“We passed a new law last year with an immediate effective date,” he said. “I think consumers had a right to rely on the statute we wrote.”

Vanderspek, however, does not like the idea of retroactivity. Anyone who bought an electric vehicle since last August clearly did not need the state-sponsored financial incentive to do so, she noted. It makes more sense to use the finite pot of rebate money to help nudge new consumers toward clean vehicles, rather than paying out for cars already on the road, she said.

Whatever form the new provisions take, a variety of factors beyond the state’s control will also affect how quickly electric vehicle adoption accelerates. Supply chain shortages have been making it more difficult for eager buyers to acquire electric vehicles. A generous $7,500 federal incentive in the Inflation Reduction Act sparked optimism, but the Treasury Department announced last week that just 14 models are eligible for that tax credit.

Still, Murray is confident that the combination of public sentiment, state incentives, and federal tax credits will soon make a measurable difference.

“We’re definitely going to see it really start to tick up,” he said.

The following commentary was written by research and modeling manager Rachel Goldstein and modeling analyst Daniel O’Brien of Energy Innovation Policy & Technology LLC. See our commentary guidelines for more information.

California’s new clean-vehicle policy will transform the world’s second largest car market, drive a nationwide electric vehicle (EV) revolution, save consumers money, and clean the air. New Energy Innovation Policy & Technology LLC research shows if the 16 “Section 177” states follow California’s plan to phase out fossil-fueled car sales by 2035, EVs could compose more than 80 percent of all new car sales across the United States in 2050.

This accelerated EV transition could extend this policy’s benefits far beyond California, creating hundreds of thousands of new jobs, preventing thousands of pollution-induced deaths, saving drivers hundreds of dollars every year, and cutting the greenhouse gas equivalent of removing an entire year’s worth of today’s car emissions.

Section 177 of the U.S. Clean Air Act allows California Air Resources Board (CARB) to enact more stringent emissions standards than those set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In August 2022, CARB approved the new Advanced Clean Cars II rule (ACC II) requiring all new cars sold in the state be zero-emission vehicles (ZEV) by 2035. California sells more cars and trucks than any other state, driving major implications for nationwide car sales and transportation emissions.

The Clean Air Act also allows other states to “piggyback” off California’s standards, helping cut emissions from vehicles inside their borders — 16 states have opted to follow earlier cleaner car standards. These Section 177 states and California make up 38 percent of the U.S. auto market, meaning ACC II adoption could transform how Americans drive. While some states automatically adopt new CARB rules, others, like Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, and New York require proactively adoption via legislation, executive order, or regulatory action.

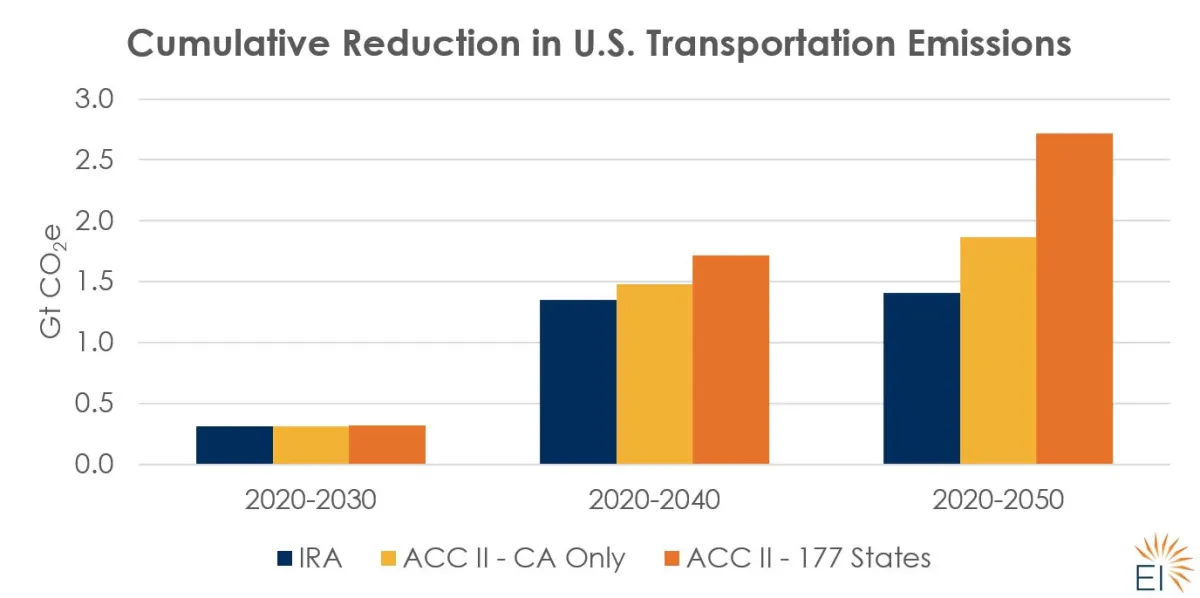

Energy Innovation modeled the impacts of the new ZEV rule using its free, open-source Energy Policy Simulator model. The results showed that if all 17 states adopt ACC II, annual U.S. transportation emissions could fall 53 percent by 2050 versus today’s levels, equivalent to avoiding the emissions of 13 coal plants operating for the next 30 years.

CARB’s decision followed the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which extended and expanded the federal EV tax credit up to $7,500. The IRA eliminated a restriction that only automakers that have sold less than 200,000 EVs can qualify for the credit and created a separate $4,000 tax credit for used EVs.

These incentives will drive consumer demand in the near term, while spurring domestic battery and EV manufacturing. But overcoming long-term adoption challenges requires ZEV standards. Following the tax credit expiration in 2032, annual EV sales could fall to pre-IRA, business-as-usual levels without ACC II adoption.

Drivers of fuel-burning cars are handcuffed to volatile gas prices. Gas prices fluctuated as much as 25 percent since 2022, largely due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. OPEC and Russia recently announced plans to cut 1.6 million barrels of oil production per day by the end of 2023, aiming to push prices even higher.

EVs are already cheaper to finance and own than gas-powered vehicles the day they are driven off the lot in most states, even if they have a higher sticker price. EVs need less maintenance and charge on the electricity grid, which has greater price stability and lower prices than the oil market. Previous Energy Innovation modeling found EV owners average $6,000 in savings over the vehicle’s lifetime thanks to lower fuel and maintenance costs.

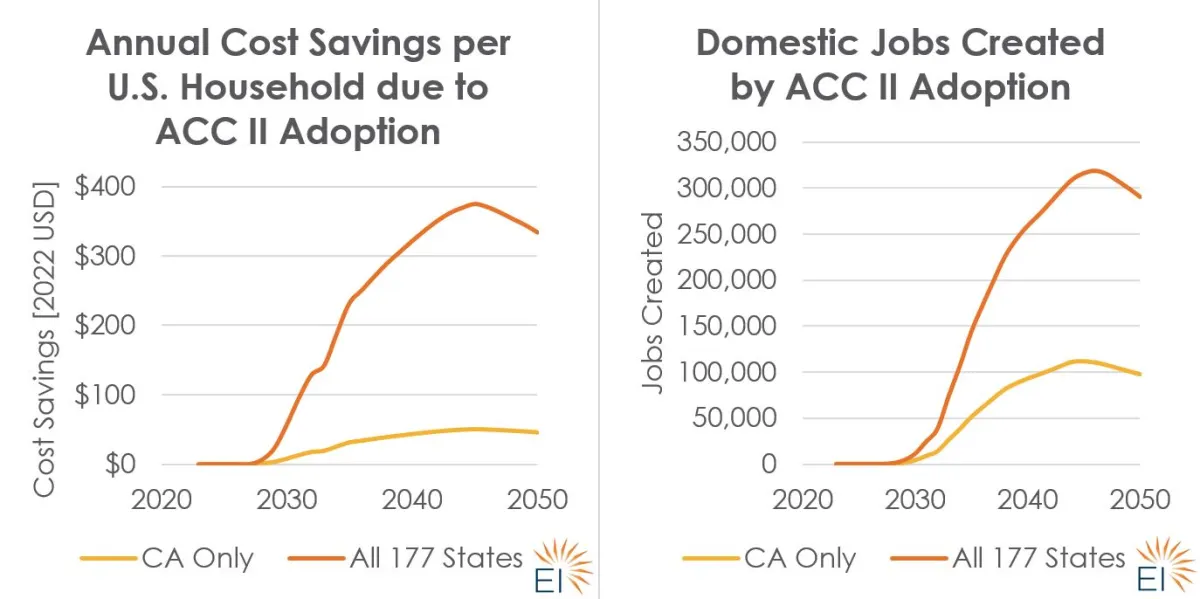

If all 177 States adopt ACC II, U.S. households could save an average of $238 annually, with savings concentrated in states that adopt the standard and offer robust EV incentives. For example, households in in New Jersey, which boasts one of the country’s highest EV tax incentives, could save $682 every year when the state implements ACC II.

ACC II adoption in all 17 states could also create more than 300,000 jobs nationwide through new EV supply chain and domestic manufacturing facilities investments.

National economic changes due to ACC II as compared with an IRA baseline

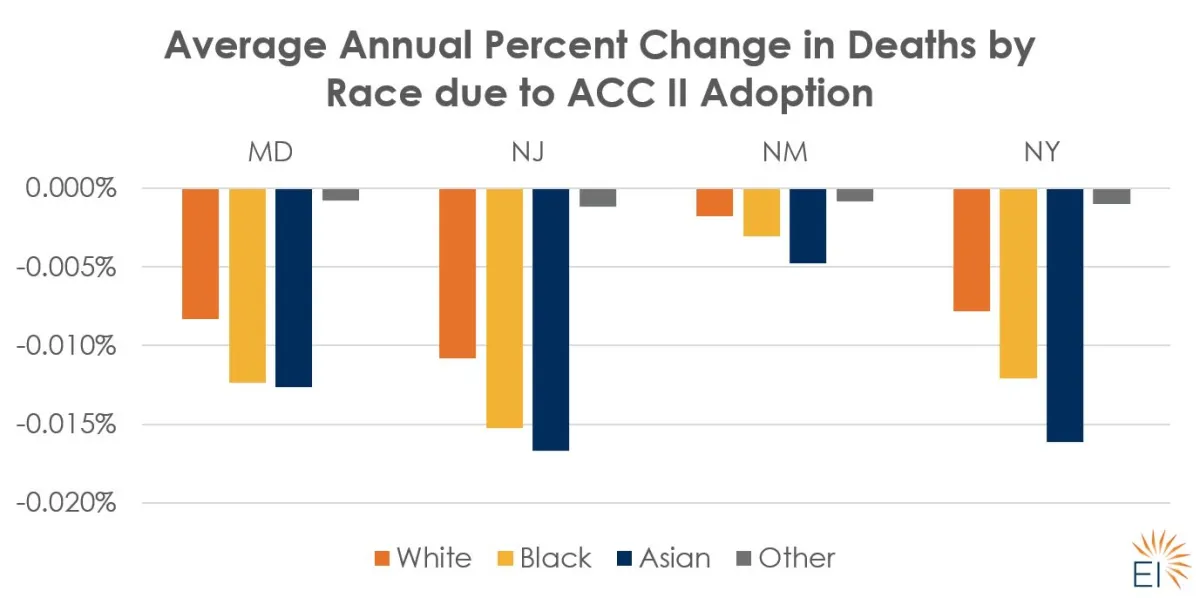

Shifting away from fuel-burning vehicles will also cut toxic nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, and particulate matter emissions which harm human health. Air quality improvements from ACC II could prevent as many as 160,000 asthma attacks and 5,000 deaths nationwide by 2050.

Improved public health will feed back into the economy. In New York, adopting the ACC II rules could prevent up to 55,000 health-induced lost workdays. These benefits will be particularly prevalent in communities of color, which experience pollution-related health impacts at significantly higher rates than the national average.

With model ZEV standards ready to adopt, state policymakers can floor it toward an electrified transportation future, delivering considerable benefits for their residents. But complementary policies are critical to ensure rapid EV adoption. Each state can further support EV market growth by developing charging infrastructure, offering state incentives for EVs, and hosting supply chain manufacturing facilities.

EV adoption is still contingent upon the buildout of a widespread, equitable charging network that ensures access to quick charging. Coordination between state and local governments, utilities, and the private sector can help build out charging infrastructure across all neighborhoods and help overcome a major obstacle to EV purchases in rural areas.

State policymakers should pair IRA tax credits with state incentives to make EVs even more price competitive. Means-based rebates and tax credits, like those in California’s Clean Cars 4 All program, should be funded to support EV access for low- and middle-income communities. Policymakers can also support the growth of their EV markets and bring more jobs home by incentivizing EV supply-chain manufacturing to their states. These facilities can bring new jobs and sources of tax revenue to their communities.

Vehicle markets are rapidly moving towards EV adoption, and states with supporting policies will be best positioned to take advantage of the benefits. ACC II will accelerate that transition, driving down carbon emissions and other tailpipe pollution while saving customers money. State lawmakers should move swiftly to adopt the ACC II rules — any delay forgoes jobs, savings, and cleaner air for their residents.

Heat pumps, induction stoves and other electric devices are increasingly seen as key to a clean energy future. And most new homes have electric service robust enough to handle them.

But older homes were not designed for big electrical loads, and millions will require updates before those new appliances can be safely plugged in.

In states like Minnesota, where old homes with natural gas furnaces and water heaters are common, upgrading electric panels “is going to be huge,” said Eric Fowler, senior policy associate for buildings at Fresh Energy, a clean energy advocacy group that also publishes the Energy News Network. “As we move toward electrification, that bottleneck is going to be the electric panel.”

In Minneapolis alone, the Center for Energy and Environment estimates owners of one- to four-unit buildings could spend between $164 million and $213 million to improve electric service. Pecan Street, a national research organization, found at least 48 million homes nationally may need electric panel upgrades.

And while changing out the electrical panel itself is fairly straightforward, bringing an older home with 60 or 100 amp service to a modern standard of 200 amps may require more extensive utility upgrades that can rack up thousands of dollars in additional costs.

Fowler said electricians modernize the panel of circuit breakers and, if needed, conduct a “service upgrade” to improve the wiring to carry more current between the home and the electric grid. “That upgrade cost can vary wildly, especially if it requires digging underground, potentially under pavement that will need repair,” he said.

One potential solution is a “smart panel” that could help manage the load, eliminating the need for a bigger utility line. While all the electrical devices running simultaneously could overwhelm a 100 amp service, a smart panel would manage those loads to ensure that limit is never reached.

“A smart panel lets you do the first upgrade without the second — you can manage more circuits with the same amount of electricity with slight adjustments in the timing of your electricity use,” Fowler said.

The Minnesota Legislature is considering House and Senate bills offering income-eligible grants to owners of homes and apartments to upgrade their electric panels to a higher amperage or purchase smart panels. The federal Inflation Reduction Act also contains home electrification incentives that could be applied to smart panel investments.

Connexus Energy, the state’s largest member-owned electric cooperative, has been promoting the technology to members. Rob Davis, communications lead for Connexus, said a coalition of businesses and clean energy advocacy groups support the measure and asked legislators to include smart panels.

While smart panels can save money over major utility upgrades, they are still an expensive undertaking. Angie’s List reported the average cost to upgrade an electric panel is $1,230, but that sum increases considerably if the project requires a new panel, additional rewiring and equipment, switches, and so forth. Some upgrades could cost thousands of dollars, especially on older homes.

The SPAN smart panel costs $4,500, not including installation, taxes and shipping. Schneider Electric’s Square D Energy Center Smart Panel lists at $2,999 but for now is only available in California. It also has a smart panel, Pulse, which works in conjunction with other appliances as part of a home energy management system that, if fully installed, will cost around $10,000, according to Wired. Lumin’s smart panel starts at $3,150.

Twin Cities Habitat for Humanity’s Mike Robertson manages Brush With Kindness, which repairs and paints existing homes. He believes the state assistance program would help low-income residents replace aging fuse boxes with devices capable of managing new electric demands.

“Historically, with this kind of technology, the early adopters tend to be rich White people, right?” he said. “If you’re having an equitable approach to decarbonization, then you have to think about disinvested communities, communities of color, where the difference in the utility bill and indoor air quality makes a difference in their lives.”

In Minnesota, Connexus has featured SPAN at a contractor event and its staff is familiar with the product. Principal technology engineer Tom Guttormson explained that power from utilities enters buildings through panels, which redistribute electricity through branch circuits to power lights, home sections and devices.

Panels have a main circuit breaker and smaller breakers. If you connect devices that, in the aggregate, draw too much power from one circuit, then it trips the main breaker, cutting power to the entire building. Building owners can usually switch the circuit back on themselves after turning off an appliance that might be causing the problem.

Common electric panels “are not intelligent devices,” he said. “New smart panels can provide the ability to monitor and control power flowing to various devices, and even let the users see the usage with a mobile device app.”

Smart panels will help consumers take advantage of time-of-use rates by allowing them to turn off home heating and cooling, electric vehicle charging, or appliances during peak demand times, he said. Those with solar could benefit, too, by selling energy during high-demand periods.

For utilities, intelligent panels provide an opportunity to improve load management and could reduce the need for widespread and costly capacity upgrades of transformers and other grid infrastructure, Guttormson said.

“We need to work together to optimize how all this works,” he said. “These conversations are ongoing, but it is all starting. This is all new territory.”

Hannah Bascom, a vice president at SPAN, learned from working at the thermostat company Nest that consumers need time to understand how new home products can improve their lives. As more companies develop smart panels, a product category will emerge and sales should grow, she said.

“The electrical panel is very well positioned to be the central artery in the brain of the home,” she said. “You can understand whole-home energy consumption by circuit by device type, and that is rich data not from the customer experience perspective but from connecting to load management programs in the future.”

A SPAN customer in Lanesboro, a small southeast tourist outpost in Minnesota, said that after just a few months of using one, he’s discovered the data has helped him save money. Joe Deden, the founder of Eagle Bluff Environmental Learning Center, built a new all-electric home with his wife, Mary, that features Tesla solar shingles on a sharply pitched roof, a Tesla Powerwall battery, and all-electric appliances.

Deden wanted a smart panel to direct energy to heating, battery storage, or other devices and to manage loads. Offering an example, he said during a below-zero day the electric backup boiler started operating, consuming three times the energy of his air-source heat pump.

After turning off the boiler, the heat pump maintained a good temperature in the home, using far less energy. He said with the panel he could show his electrician and heating technician “that something was amiss” in the heating system that would require some adjustments. Accessing household appliance data is one of the strengths of smart panels, Deden said.

Being able to easily turn off power to his office or other parts of the home to “save a load” when not needed is another advantage. “The ability to monitor and shed loads remotely is the key,” he said. “Being able to see remotely what’s happening and to be able to control things is, to me, a great peace of mind.”

A lack of inventory from auto manufacturers and a shortage of fast-charging options in rural areas are among the factors slowing progress toward Minnesota’s state government fleet electrification goal.

The Minnesota Department of Administration set a target in 2020 to make 20% of its vehicle fleet electric by 2027, part of an overall strategy to reduce state fleet fossil fuel consumption by 30% by 2027 from a 2017 baseline.

The state would have had to replace more than 400 gas vehicles with electric models per year since 2021 to meet that target, but state officials contacted by the Energy News Network were unable to say exactly how many electric vehicles the state has purchased overall. The Department of Transportation, a leader in electric vehicles among agencies, has 14. The Department of Natural Resources has four.

“We’re moving forward slower than I would like,” said Holly Gustner, fleet and surplus director for the Department of Administration.

The state has more than 15,000 vehicles, with the most progress on electrification in the light-duty category, which represents a third of the vehicles.

In 2021, the state’s light-duty category was dominated by flex-fuel vehicles capable of running on high ethanol blends, accounting for 55%. Hybrids followed at 22% and regular internal combustion engines at 15%. The rest were electric, plug-in hybrid and diesel-run models.

The state’s plug-in electric, hybrid and flex-fuel vehicles contributed to a 17% drop in emissions from light-duty vehicles in 2020 and 2021, according to administration data.

Vehicle cost plays a role when agencies make purchasing decisions, but the total cost of ownership favors electric. While electric vehicles command a higher initial expense, electricity costs less than gas, and the cars require less maintenance, said Marcus Grubbs, director of the Department of Administration’s Office of Enterprise Sustainability. Agencies also like the advantage of having fully charged vehicles available every morning so staff will not have to refuel during the day.

But agency leaders say many state vehicles have no easy electric replacement option yet, and manufacturers of those that do — typically cars, pickups and SUVs in the light-duty category — are often months behind in deliveries.

Automakers have been prioritizing states such as California and Massachusetts, which have requirements to make electric vehicles available. Gustner said one factor expected to increase Minnesota’s access to electric vehicles is its adoption of clean car standards, which have helped increase supply in other states as their demand increased. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency adopted the California-developed standards last year and has been finalizing rules.

“I think once that rulemaking is completed, and we actually sign off as one of the clean car states, I think we’re going to see more cars coming this way,” Gustner said.

Grubbs said the government uses vehicles in such specific ways that finding electric replacements has not been easy. As an example, he pointed to a new electric transit van that “looked great” until he discovered it had no lift for disabled passengers.

“Availability has been the greatest challenge,” said Jed Falgren, state maintenance engineer with the Minnesota Department of Transportation.

His agency may have the biggest obstacles in meeting the state goal because light-duty vehicles are only 13% of its fleet. The rest are medium- and heavy-duty vehicles — including 800 snowplows — which currently have no practical electric replacement models available, he said.

Falgren said the agency has spoken to trucking manufacturers about replacing heavier vehicles with models fueled by hydrogen or compressed natural gas, which pollute less than plows now being used, he said.

New, greener snow plow models have begun to come onto the market, but how well they work remains a question. For example, a recent test in New York City found electric snowplows “basically conked out after four hours,” according to a city official there.

“Our plow trucks have got to run and be available to run 24 hours a day,” Falgren said. “So there’s a lot of technological nuts to crack before we can go widespread on some of those [vehicles].”

The Department of Natural Resources wants to add to its four-vehicle electric fleet and has ordered more. Aaron Cisewski, fleet and materials manager in the DNR’s Operations Services Division, said the agency covers a huge geographical area of Minnesota, with state parks and other offices spread far apart. Employees have expressed concerns about range reduction caused by cold weather and trailer towing, which the agency does a lot of in state parks.

The department has deployed Chevy Bolts in state parks, where they operate in a limited area and are recharged nightly, he said.

Gustner said developing a charging network for state vehicles has been a challenge. Parts of the system are robust, such as around the Capitol complex, where 65 chargers operate. But outstate Minnesota is a different story even as the state continues to add chargers in more rural locations.

Fast chargers are becoming a priority because most state workers will be “topping off” their vehicles rather than needing a full charge, Gustner added. But for now, the charging infrastructure in some areas “does not enable the flexibility [of long-distance travel] right now, or doesn’t exist, or isn’t perceived to exist,” he said.

Minnesota is better poised, despite the weather, to take advantage of transitioning to electric vehicles than some other states. The state government could replace more than half of its light-duty vehicles, a better average than Colorado or North Carolina, according to a National Renewable Energy Laboratory 2022 study of state fleet electrification.

Using 2-year-old data, the study found the driving range of electric vehicles on the market can meet 93% of the state’s light-duty needs. The study projected a $4.7 million savings over the lifetime of vehicles and a reduction of more than 10,000 metric tons of greenhouse gases.

While the new clean car standards are expected to help, Brendan Jordan, vice president of transportation and fuels at the Great Plains Institute, said Minnesota’s state government could have an easier time procuring electric vehicles if the state had additional policies that incentivize their purchase by residents and businesses.

“Other states offer incentives on the medium- and heavy-duty side, which we don’t offer,” he said. “Companies look at what kind of policy environments are in place when they’re deciding where to ship the cars.”

The Minnesota Future Fuels Coalition, which includes the Great Plains Institute and Energy News Network publisher Fresh Energy, has been advocating for the recently introduced Clean Transportation Standard Act that would require the carbon density of fuels to decline to zero by 2040.

There’s also legislation that would “establish a preference” for electric vehicles for the state’s fleet. Other preferred vehicles include hybrids and those that can run on cleaner fuel. The law would solidify a preference already practiced by agencies.

Should either or both bills pass, they would give the state government an extra benefit of removing some obstacles from electric vehicle acquisitions, Jordan said.

Either way, preparations continue for an electric future. With assistance from Xcel Energy and a consultant, MnDOT created a software tool that uses data captured from its vehicle fleet to determine suitable electric replacements, he said. In addition, plans are emerging for training mechanics to work on light-duty electric vehicles.

And the agency must get used to paying more upfront for electric vehicles while understanding the cost of ownership will be less in the long run.

“MnDOT does not mind being on the leading edge of technologies,” Falgren said. “The leading edge is a good spot to be.”

The following commentary was written by Olivia Ashmoore, a policy analyst at Energy Innovation, and Ashna Aggarwal, an associate at RMI. See our commentary guidelines for more information.

Climate leadership in Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin could revitalize the Midwest. And the timing couldn’t be better.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is the biggest clean energy investment in American history, generating tremendous opportunity for pro-climate state officials to pass bolder policy and take advantage of billions of dollars in new federal investments in clean energy technologies.

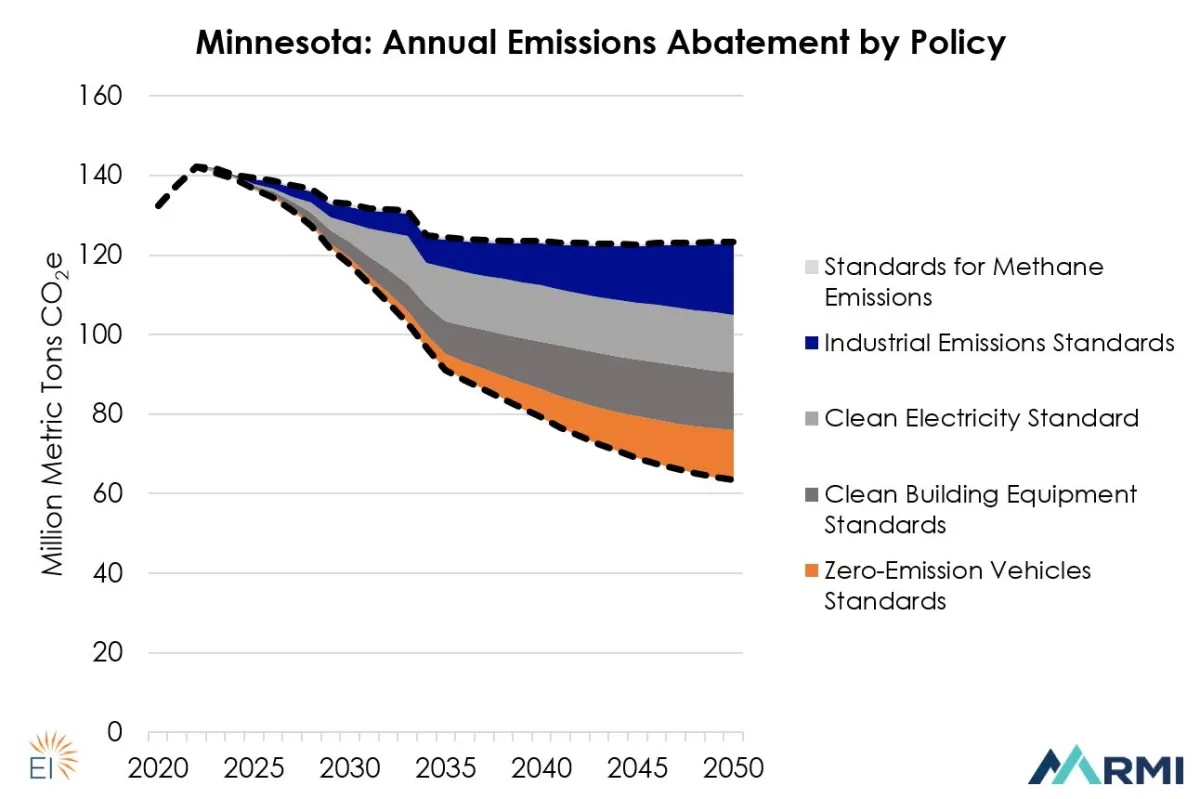

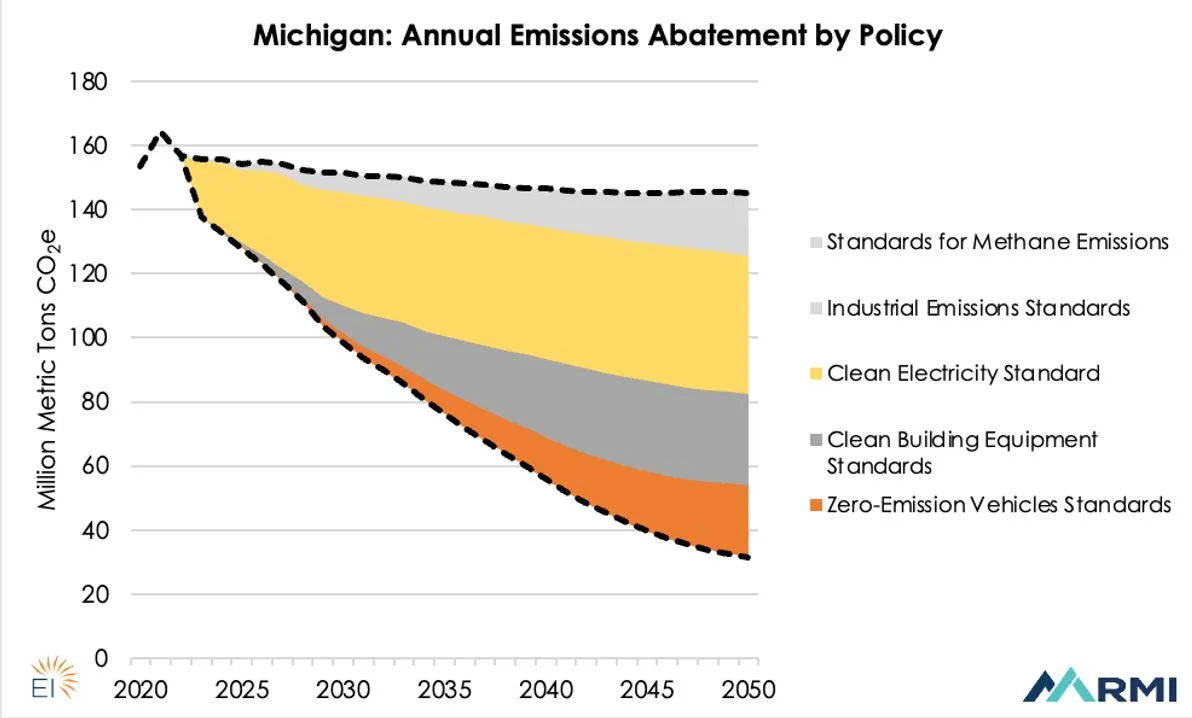

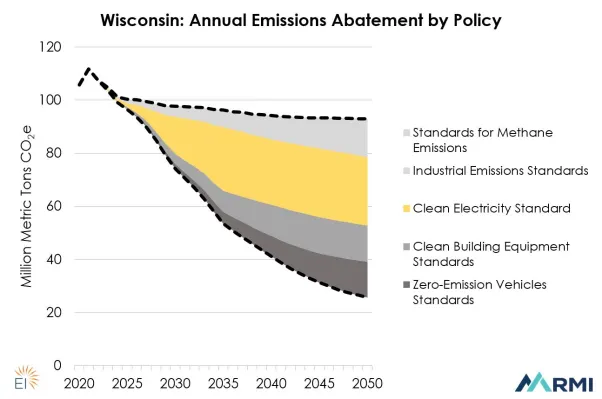

Recent Energy Innovation Policy & Technology LLC and RMI modeling using the new state Energy Policy Simulators finds just five policies can effectively cut emissions in any state—even those with quite different greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions sources. The analysis also shows adopting strong climate policies would boost local economies, create jobs, and protect public health. The most impactful policies are: clean electricity standards, zero-emission vehicle standards, clean building equipment standards, industrial efficiency and emissions standards, and standards for methane detection, capture, and destruction.

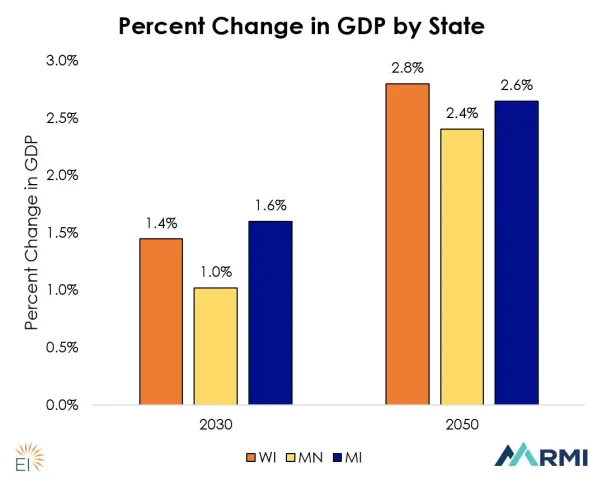

In Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin, adopting these five policies would help achieve climate targets and boost GDP, though the most impactful policies vary by state. By 2050, Minnesota’s GHG emissions could drop by 50% below 2005 levels, Michigan’s by 85%, and Wisconsin’s by 80%.

.webp)

In Minnesota, policymakers committed to climate action took office this January, resulting in passage of a new law requiring 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040. Thanks to recent coal power plant retirements, Minnesota was already on track to meet its GHG reduction goals for 2025. Now, a faster clean energy pace will help the state reach its goals of slashing emissions 80% below 2005 levels by 2050. However, the modeling shows the state will also need to tackle transportation, industry, and agriculture emissions.

Using the new Minnesota Energy Policy Simulator, Energy Innovation and RMI find adopting the top five policies would cut emissions in these sectors to achieve economy-wide reductions of 50% below 2005 levels by 2050 — major progress toward the state’s goal. These five policies would also stimulate Minnesota’s economy, adding more than 30,000 new jobs in 2030, 100,000 new jobs in 2050, and growing GDP 2.4% in 2050.

In 2020, transportation was the largest source of in-state emissions and industrial emissions are projected to rise through 2050. The modeling shows joining other states in following the new Advanced Clean Cars II standard (ACC II), requiring 100% of car and small truck sales to be zero-emission vehicles (ZEV) by 2035, and 100% of heavy-duty truck sales to be zero-emission by 2045, can eliminate the majority of transportation sector emissions by 2050.

Industrial emissions standards or an industrial carbon cap program would require industrial facilities to switch from fossil fuels to electricity, renewable biofuels, and hydrogen. Minnesota is already advancing projects to integrate cleaner fuels — Gov. Tim Walz proposed new funding for biofuel infrastructure in the state’s budget and a Minnesota utility is piloting a new program to use hydrogen fuel. Industrial emissions standards that shift 100% of fossil fuel use to a mix of electricity and hydrogen for low-temperature and medium- to high-temperature heat by 2050 could reduce industry emissions 75% in 2050, accounting for a quarter of the potential reductions of five policy package.

Our modeling did not address the large agricultural sector in the state, which contributes 19% of Minnesota’s emissions. But the state is exploring policies that can offset agricultural emissions. Well-designed land use policies, like wetland restoration or grassland management, can close the gap between the five-policy scenario and the 80% reduction goal.

Minnesota has made major progress. Capitalizing on the IRA by adopting additional policies can cement its leadership, create new clean energy jobs, and ensure the state reaches its 2050 goal.

Michigan is laying the foundation for bolder climate action. In her 2023 State of State address, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer pledged to make Michigan “a hub of clean energy production.” It’s already happening — Ford just announced plans to set up an electric vehicle (EV) battery manufacturing facility 100 miles west of Detroit.

Last year, the state released a new climate plan, outlining policies to reduce emissions 52% below 2005 levels by 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2050. Previous Michigan EPS analysis by 5Lakes Energy, the Michigan Environmental Council, NRDC, Energy Innovation, and RMI found the state’s climate plan would cut emissions 50% by 2030 — nearly reaching the state’s near-term goal.

Strong implementation of Michigan’s climate plan sets the stage for further climate progress to reach the 2050 net-zero target. The state’s plan includes key components of the five policies, but more ambition is needed. Adopting our five recommended policies would cut Michigan’s emissions 86% relative to 2005 levels by 2050. The five policies would also spur economic development as clean energy infrastructure is built out, creating more than 70,000 jobs in 2030 and 153,000 jobs in 2050, and growing GDP 2.67% by 2050.

An 80% by 2030 and 100% by 2035 clean electricity standard would cut emissions more quickly than the climate plan target of 60% renewables by 2030 — though this is a solid foundation. The clean electricity standard accounts for a whopping 67% of total emissions cuts achieved by the five-policy package in 2030. Michigan could also move to adopt ACC II and set ambitious ZEV standards. Though a strong ZEV standard would only account for 5% of total emissions cuts in 2030, it would grow to 25% in 2050 as more gas vehicles are replaced with EVs.

With new majorities in the Michigan legislature and IRA incentives for clean energy technologies across sectors, the state is well positioned to implement — and go beyond — the policies laid out in the climate plan.

In Wisconsin, Gov. Tony Evers and state offices have made plans to address climate change and move towards carbon-free electricity. In 2020, the Governor’s Task Force on Climate Change produced a detailed report on reducing statewide emissions and now is the time to execute. If adopted in Wisconsin, our top five policies would reduce emissions 80% below 2005 levels by 2050 and add 39,000 new jobs in 2030, add 82,000 jobs in 2050, and grow GDP 2.8% in 2050.

The most impactful policy for Wisconsin is a 100% clean electricity standard by 2035, which accounts for half of the five policies’ emission reductions. The clean electricity standard alone would cut emissions 40% in 2035. This one policy would also be an economic juggernaut, creating 14,000 new, in-state jobs in 2035 and saving residents money by deploying lower-cost clean electricity. A separate Energy Innovation report finds replacing Wisconsin’s aging coal plants with new regional wind energy would yield savings up to $290 million annually compared to running existing coal.

Wisconsin can take advantage of Gov. Evers’ climate leadership to realize new economic opportunities. Among these three Midwestern states, Wisconsin could see the greatest GDP growth by implementing the top five policies — an estimated 2.8% growth in 2050.

As our modeling demonstrates, just five climate policies would build on the progress these states have made to date, solidify Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin’s leadership, and revitalize their economies. Now is the time to act on ambitious plans. The IRA dramatically lowers the cost of clean energy technologies and new climate momentum means these states are positioned to deliver — as demonstrated by Minnesota’s passing of 100% clean energy law.

Sharing best practices and building infrastructure across the region — such as EV charging networks and transmission lines — can amplify the actions of any one state alone. The collective action of these three states could revitalize America’s industrial heartland. It’s now up to Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin to take advantage of this opportunity.

Rhode Island’s top utility regulator says a statewide moratorium on new gas hookups is on the table as the state works to meet its ambitious climate goals.

“That doesn’t mean it happens tomorrow,” said Ronald Gerwatowski, chair of the Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission, during a proceeding Thursday. “But it surely begs us all to ask the question: If not tomorrow, then when?”

Gerwatowski’s comments came as the commission held its first technical conference in its investigation into the future of natural gas.

A wide-ranging discussion followed about the many challenges and conundrums facing the commission in the so-called “Future of Gas” docket. Regulators opened the investigation in response to the passage of the state Act on Climate, which includes a mandate to zero out greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Building emissions, including those that result from the use of natural gas, account for about 35% of the state’s total emissions. The commission regulates the gas distribution system, which is operated by Rhode Island Energy.

The purpose of the first proceeding was “to prepare the commission to make big and ambitious decisions,” said commissioner Abigail Anthony.

The breadth of the challenge ahead was laid out by Rhode Island Energy executives, who provided a factual representation of the state’s gas distribution system. The company has more than 273,000 residential, commercial and industrial gas customers served by some 3,200 miles of gas distribution main, said Michele Leone, vice president of gas.

Through the company’s ongoing pipeline replacement program, 60 to 65 miles of gas main are replaced every year, she said. About half of the mains have been replaced with less leak-prone pipes so far.

Whether or not to continue that program is a particularly vexing question for the commission, Gerwatowski said. Replacing leak-prone pipes is both a safety issue and an environmental issue, he said. Right now, those infrastructure investments are factored into the rate base and are depreciated over 40 years, a timeline that is now far too long.

“We could depreciate it more quickly, but that has an impact on rates. So what do we do here?” Gerwatowski said. “Do we stop the program on the assumption we’re going to close the system down,” allowing for some continued methane leaks?

Or, he said, do they allow the program to continue, and then likely face lawsuits over who should be responsible for the stranded costs once the assets are no longer in use?

Ben Butterworth, director of climate, energy and equity analysis at the Acadia Center, said in response that the commission must prioritize safety above all else first, but could perhaps investigate ways to repair pipes rather than replace them. That would reduce costs and the time period over which the utility is spreading those costs.

“That’s why it’s essential to determine a plan as soon as possible for the future vision of the gas system,” Butterworth said. “It might make sense to do it on a case-by-case basis.”

When it comes to transitioning from the use of natural gas, the state will need to find pathways “that ensure safety and reliability, equity, and affordability,” said Dan Aas, director at E3, an energy consulting firm representing Rhode Island Energy.

He recommended a “portfolio-based” approach that might include a combination of air-source heat pumps, hybrid electrification, renewable natural gas, and geothermal.

He noted that in California, Pacific Gas and Electric is experimenting with targeted electrification, in which they target for electrification a small cluster of customers on a segment of the distribution system that is costly to maintain.

But the prospect of converting hundreds of thousands of residential customers to air-source heat pumps poses another daunting question, Gerwatowski said.

“There’s a huge upfront funding cost — where does the funding come from?” he said.

The commission also heard from speakers representing consumer perspectives. Chelsea Siefert, director of planning and development for the Quonset Development Corp., a 3,200-acre business park in North Kingstown with more than 220 companies, urged regulators to consider the impacts of phasing out natural gas on industrial manufacturers.

For example, she said, burning natural gas generates the high temperatures Toray Plastics requires to convert plastic pellets into plastic film. Toray employs about 600 people at its Quonset facility.

And Jennifer Wood, executive director of the Center for Justice, which represents low-income utility consumers, called on the commission to prioritize any electrification efforts in the neighborhoods that have been impacted by fossil-fuel pollution for generations due to redlining and other discriminatory lending practices.

In the city of Providence, those old redlined areas now coincide with areas with the highest poverty rates and incidences of childhood asthma, she said.

“The remedies for meeting the goals of the Act on Climate should be targeted to the neighborhoods that have been the most adversely impacted along the way,” Wood said.

As the next step in the process, the commission will issue an invitation for interested parties to apply to join a stakeholder committee. The committee’s first meeting will likely be next month, said Todd Bianco, chief economic and policy analyst. The overall goal is to have a report with recommendations to the commission by next spring, he said.

Vermont’s only natural gas company is exploring possible sites for its first fossil-fuel-free, networked geothermal project, a heating and cooling technology that could be a natural fit for a company already skilled at designing and constructing piping systems.

“It’s a near-perfect overlay of our current business model,” said Richard Donnelly, director of energy innovation at Vermont Gas Systems, which currently serves about 55,000 customers.

Legislation pending before the House Committee on Environment and Energy could help speed such geothermal innovation. The bill, still awaiting a number, directs the state Public Utility Commission to adopt rules for permitting thermal energy networks — underground loops of liquid-filled pipes that are heated or cooled by the earth and connected to multiple buildings.

It would authorize any entity, not just existing utilities, to operate geothermal networks as regulated utilities, enabling them to recover their costs through the rates paid by customers.

“An electric cooperative, a homeowners’ association, a municipality, a large fuel dealer — they could become utilities so they could access the capital needed and recover their costs over time,” said Debbie New, a community organizer who helped draft and is promoting the legislation.

Emissions from heating and cooling buildings represent about 34% of Vermont’s carbon dioxide emissions. The state must find ways to reduce those emissions in order to meet its climate goals, and geothermal could be a key part of the solution, advocates say.

A geothermal system — or ground-source heat pump — consists of an underground piping network and a connected heat pump inside the building. Powered by electricity, the pump moves heat from the pipes to warm the building in cold weather. In hot weather, it reverses the process and draws heat from the building into the ground.

The pipes are placed at a depth where the earth’s temperature is relatively constant, around 50 degrees in Vermont.

The systems have no visual impact because they are underground. The pumps are significantly more efficient than other forms of heating and cooling, “and if the electricity being used is renewable, you can envision a really, truly decarbonized future,” said Jake Marin, senior emerging technology and services manager at Efficiency Vermont.

The downside, however, is cost.