Offshore wind is going through some rough waters.

Last week, the industry saw a big setback as Danish wind giant Ørsted canceled its Ocean Wind I and II projects off the New Jersey coast. The company blamed supply chain issues and rising interest rates for the decision — issues that had been threatening wind projects up and down the East Coast for months.

So far, those other major projects are still slated to be built, and they’re critical to keeping the Biden administration’s clean energy goals on track. But to make sure that happens, other Northeast states like New York will have to pick up New Jersey’s slack, Politico reports.

Still, industry analysts aren’t sure state action will be enough to preserve Biden’s wind goals. That’s why governors and lawmakers are calling on the federal government to step in to speed up offshore wind farm permitting and make sure projects can fully take advantage of federal tax incentives, E&E News reports.

But there’s good news for the industry, too. On the same day New Jersey’s two projects sunk, the Biden administration approved what is slated to be the country’s biggest offshore wind farm: a 176-turbine project off Virginia’s coast that’ll be able to power as many as 660,000 homes.

💰 Financing a “carbon bomb”: Banks around the world financed “carbon bomb” projects to the tune of $150 billion last year, paving the way for developments that could each pump a gigaton of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. (Guardian)

🛠️ Clean jobs are coming: The Inflation Reduction Act is expected to create more than 300,000 construction jobs annually as it spurs clean energy development, plus another 100,000 jobs in operating those projects. (Canary Media)

🔋 Battery shortages aren’t so bad: As automakers slow their rollouts of electric vehicles, an industry trade group says it will actually help battery manufacturers scale up and rely less on China for materials. (E&E News)

🧾 Carbon tax collab: Three Republicans introduce a bill to levy fees on imports from countries with high carbon emissions, and Democratic senators look to find common ground. (E&E News)

🚂 Ticket to electrify: The world’s first battery-powered heavy freight locomotive made its debut last week, but electrifying the U.S. rail system is still in very early stages. (Canary Media)

🛫 Prepare for takeoff: The journey of a Beta Technologies’ electric plane down the East Coast provides a glimpse into the future of electric aviation. (New York Times)

⚡ Hawaii’s clean power success: A Hawaii utility cooperative says its publicly owned grid model has helped it reach its goal of generating 60% of its electricity from clean energy sources. (Canary Media)

🏁 A Texas-sized climate win: Austin, Texas, becomes the largest city in the country to drop minimum parking requirements for new developments in a move aimed at lowering emissions and increasing housing supply. (Texas Tribune)

🏗️ Buildings are getting cleaner: Inflation Reduction Act incentives for building electrification, efficiency measures, and solar and storage installation could help cut building emissions as much as 70% by 2035, a U.S. EPA analysis finds. (Utility Dive)

As the first frost visits the mountains of western North Carolina, thousands of households are bracing themselves. Thinly insulated manufactured homes will provide little barrier to the cold. Gaps around doorways will invite it in. Old furnaces, if they work at all, will consume already strained monthly budgets.

A lucky fraction of these families will benefit from a flood of federal weatherization dollars headed to the state thanks to the bipartisan infrastructure law passed two years ago.

But for Buncombe County residents who don’t or can’t take advantage of the decades-old Weatherization Assistance Program, there’s an innovative nonprofit in Asheville working to fill the gaps.

Since 2017, Energy Savers Network has helped some 1,000 households cut down on energy waste by tightening air seals, adding DIY storm windows, and performing other upgrades at no cost to occupants.

Designed to help complement, not supplant, federal weatherization funds, the project’s success is due in part to its speed and simplicity. And its track record has earned it a prominent place in Buncombe and Asheville’s plans for 100% renewable energy.

“By embracing local, clean energy sources, going electric and saving energy,” said Buncombe County Council Chairperson Brownie Newman, in a press release, “we’re taking essential steps toward combating the climate crisis while ensuring a just transition for all residents.”

Distributed largely by community action agencies formed during the War on Poverty, weatherization assistance has evolved to become one of the federal government’s most successful energy efficiency programs, helping some 7 million low-income households nationwide reduce energy waste since 1976.

But deploying assistance still presents a host of challenges: identifying potential recipients and earning their trust, hiring and training the workers who can perform the work, and remediating homes with immediate health and safety repair needs. Clients-to-be in Buncombe County may spend a year or more on a waitlist.

Though southwestern North Carolina is set to receive $4.8 million over five years as part of the state’s $90 million share of the infrastructure law, just 440 single-family households are expected to benefit over the 13-county region.

With some 18,000 families living in energy-inefficient manufactured homes in Buncombe County alone, the demand for energy efficiency upgrades far exceeds the supply of assistance.

That’s where Energy Savers Network comes in. The concept began 100 miles west in Hayesville, where members of the Good Shepherd Episcopal Church “answered a combined moral calling to help the poor and be good stewards of Creation,” Interfaith Power and Light wrote.

The team of parishioners and other volunteers helped families cut their energy use by 10% to 20% — first conducting an audit, then tracking down free or low-cost materials, and finally performing simple upgrades like replacing lighting or adding weather stripping free of charge.

When church member Brad Rouse, a one-time financial and utility consultant, decided to devote his time to climate causes and move to Asheville, he brought Good Shepherd’s idea with him.

Today, the Energy Savers project is staffed by a small team at the Green Built Alliance, but the volunteer spirit and the simplicity remain.

At farmers’ markets, community events, and through word of mouth, potential clients indicate interest. Staff then follow up to ensure they meet the income guidelines and can otherwise benefit from energy efficiency upgrades.

“We do a lot of the intake over the phone,” said Hannah Egan, the project’s outreach and resource manager, “explaining what we might be doing, what we need from them, how long the appointment could last.”

A visit is scheduled. A staff person and two to three volunteers arrive and do what they can accomplish in a day. “Once we’ve qualified the client over the phone, we just go there with our crew,” Egan said. “It’s just a lot easier to do it all in one go.”

They seal air leaks. They replace lightbulbs, insulate hot water heaters, and reinforce single-paned windows. “And then more as we see fit,” Egan said, “because every home is different. Our goal with that is to make homes more comfortable, reduce their energy usage and their utility bills.”

On average, the improvements help occupants cut energy use about 15%, fueling a virtuous cycle. “A lot of times, when we do get in their homes,” Egan said, “they’re really happy with the work we do,” prompting friend and family referrals. “That’s been a main source of client recruitment since COVID.”

Hiring building performance expert Kelvin Bonilla onto the Energy Savers team, Egan said, “drastically improved the quality of our work.” A native of Honduras, Bonilla has also helped spread the word to the county’s sizable Spanish-speaking community.

“He’s a really good people person,” Egan said. “He’s very professional, and he knows how far to go and when to stop.”

Many times, Energy Savers refers clients to Community Action Opportunities, the local provider of weatherization assistance. In some cases, they can return to repair or replace ailing furnaces with high-efficiency heat pumps. Dogwood Health Trust also funds minor home repairs, such as replacing a door or damaged flooring.

With additional support from Duke Energy, the city and the county, the team serves roughly four households a week and nearly 200 a year. From start to finish, the process takes between two and six weeks.

Moving forward, the hope is to both expand the scope of work and serve as a model to other communities. “We asked for an increase,” Rouse said. “There’s still a little bit of a hole. In order to expand the way we would really like to expand, we need more money.”

Climate and clean energy advocates in New Hampshire say a pending proposal to define nuclear power as clean energy could undercut solar and wind power in the state.

Though the details are still in the works, state Rep. Michael Vose, chair of the legislature’s science, technology, and energy committee, is drafting a bill that would allow nuclear power generators, such as New Hampshire’s Seabrook Station, to receive payments for contributing clean energy to the grid.

“The broad idea is that, long-term, we can hope and expect that that reliable source of baseload power will always be there,” Vose said. “It won’t be driven out of business by subsidized renewable power.”

Some environmental advocates, however, worry that the proposal would provide unnecessary subsidies to nuclear power while making it harder for solar projects to attract investors.

“It’s just another way to reduce support for solar,” said Meredith Hatfield, associate director for policy and government relations at the Nature Conservancy in New Hampshire.

New Hampshire’s renewable portfolio standard — a binding requirement that specifies how much renewable power utilities must purchase — went into effect in 2008. To satisfy the requirement in that first year, utilities had to buy renewable energy certificates representing 4% of the total megawatt-hours they supplied that year. The number has steadily climbed, hitting 23.4% this year.

New Hampshire was the second-to-last state in the region to create a binding standard — Vermont switched from a voluntary standard to a mandated one until 2015. New Hampshire’s standard tops out at 25.2% renewable energy in 2025, but the other New England states range from 35% to 100% and look further into the future.

Vose, however, worries that even New Hampshire’s comparatively modest targets could put the reliability of the power supply at risk.

“Until we can have affordable, scalable battery storage, the intermittency of renewables is going to guarantee that renewables are unreliable,” Vose said. “And if we add too many renewables to our grid, it makes the whole grid unreliable.”

That idea has been widely debunked. Grid experts say variable renewables may require different planning and system design but are not inherently less reliable than fossil fuel generation.

The details of Vose’s clean energy standard bill have not yet been finalized. A clean energy standard is broadly different from a renewable energy standard in that it includes nuclear power, which does not emit carbon dioxide, but which uses a nonrenewable fuel source. Those writing the legislation, however, will have to decide whether it will propose incorporating the new standard into the existing renewable portfolio standard or operating the two systems alongside each other.

Clean energy advocates say they are not necessarily opposed to a clean energy standard, but argue it is crucial that such a program not pit nuclear power and renewable energy against each other for the same pool of money. And they are concerned that that’s just what Vose’s bill will do.

“While we would welcome a robust conversation about how to design a clean energy standard, I fear that’s not what this bill is,” said Sam Evans-Brown, executive director of nonprofit Clean Energy New Hampshire.

If a clean energy standard is structured so both nuclear and renewables qualify to meet the requirements, clean energy certificates from nuclear power generators would flood the market, causing the price to plummet. Seabrook alone has a capacity of more than 1,250 megawatts, while the largest solar development in the state has a capacity of 3.3 megawatts. Revenue from renewable energy certificates is an important part of the financial model for many renewable energy projects, so falling prices would likely mean fewer solar developments could attract investors or turn a profit.

At the same time, nuclear generators could sell certificates for low prices, as they already have functioning financial models that do not include this added revenue. Nuclear could, in effect, drive solar and other renewables out of the market almost entirely, clean energy advocates worry.

“The intention of the [renewable portfolio standard] has always been about creating fuel diversity by getting new generation built, and a proposal like that would do the opposite,” Evans-Brown said.

A single standard that combines nuclear and renewables could also hurt development of solar projects in another way, Hatfield said. When New Hampshire utilities do not purchase enough renewable energy credits to cover the requirements, they must make an alternative compliance payment. These payments are the only source of money for the state Renewable Energy Fund, which provides grants and rebates for residential solar installations and energy efficiency projects.

“If you add in nukes and therefore there’s plentiful inexpensive certificates, then you basically have no alternative compliance payments,” Hatfield says. “It could potentially dry up the only real source we have in the state for clean energy rebates.”

Though Vose and the bill’s other authors have not yet released the details of the proposal, he has indicated that he would not like the new clean energy standard to significantly increase costs for New Hampshire’s ratepayers. The existing standard cost ratepayers $58 million in 2022, when utilities were required to buy certificates covering 15% of the power they supplied, according to a state report issued last month.

The legislation may meet the same fate as last year’s effort, Vose acknowledged, but he is still eager to get people talking about the issue.

“Even if we can’t get such a standard passed in this session,” he said, “we can at least begin a serious discussion about what a clean energy standard might look like.”

Ammonia production is crucial in making fertilizers that feed half the world's people. Traditionally, this process has been a major contributor to global CO2 emissions due to its reliance on production using natural gas. The integration of hydrogen as a cleaner alternative presents a transformative opportunity.

For over a century, the Haber-Bosch process has been instrumental in agriculture, facilitating the mass production of fertilizers. This method combines nitrogen with hydrogen, traditionally sourced from fossil fuels, to create ammonia.

However, it's a major source of CO2 emissions, producing up to 2.5 tons of CO2 for each ton of ammonia. As a result, current ammonia production methods, using the Haber-Bosch process, are responsible for about 1.8% to 2% of global CO2 emissions.

The shift towards using green hydrogen, derived from water electrolysis using renewable energy, represents a major stride in reducing the environmental footprint of fertilizer production. Such a transition aligns with global carbon reduction goals and is crucial for sustainable low-carbon agriculture.

While green hydrogen's integration in ammonia production can potentially reduce greenhouse gas emissions by nearly 100%, eliminating approximately 5 tons of CO2 for every ton of fertilizer produced, significant challenges remain. The high cost of green ammonia, currently two to three times that of conventional ammonia, poses a major barrier. Nevertheless, ongoing technological advancements and declining renewable energy costs are gradually addressing these challenges.

International efforts, as evidenced by projects like Statkraft AS in Norway and collaborations in the Netherlands, underscore the industry's commitment to this transition. These projects, often requiring government support and subsidies, are pioneering the shift towards green hydrogen in ammonia production.

Transitioning to green hydrogen for ammonia production has implications beyond environmental benefits. With global food production heavily reliant on ammonia-based fertilizers, sustainable production methods are imperative for future food security. As the global population rises, the demand for efficient, eco-friendly fertilizers will continue to increase.

Imagine a world where the skyscrapers, cars, and bridges that make up our daily lives are all contributors to a looming environmental crisis. That's the reality of today's steel industry – a crucial yet carbon-intensive part of our modern world. In 2022 alone, the industry was responsible for a staggering 2.7 billion tons of CO2 emissions, about 7% of the global total. And with the demand for steel expected to soar by 35% by 2050, the challenge is clear: How can we continue to build our world without breaking our planet?

Hydrogen emerges as a potential game-changer for the steel industry. This lightweight gas could revolutionize steelmaking by replacing coal and significantly reducing carbon emissions. The key technology here is the Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) process.

This method extracts oxygen from various iron ore forms (like sized ore, concentrates, pellets, etc.) and produce metallic iron without reaching the melting point, that is staying below 1,200 °C (2,190 °F), far less than traditional methods.

This process is noted for its energy efficiency. When compared to traditional blast furnace methods, steel production using DRI significantly reduces the need for fuel. Commonly, DRI is transformed into steel in electric arc furnaces, utilizing the heat generated by the DRI product itself.

It also allows for the production of steel closer to mining sites, reducing transportation costs and emissions.

DRI plants, with lower initial capital investment and operating costs, are perfectly suitable for countries with limited high-grade coking coal but available steel scrap for recycling. Direct-reduced iron, comparable in iron content to pig iron, is an excellent feedstock for electric furnaces used by mini mills, allowing them to use lower grades of scrap or to produce higher grades of steel.

The blue box is where the iron ore oxide is converted into iron by removing the oxide. Oxide (oxygen) is removed either using carbon or hydrogen in the heated chemical reaction. This iron then goes into the steel making process at the same location or at another location.

Currently, hydrogen-based steel is more expensive. The economic viability of “green steel” production is influenced by the cost of green hydrogen. But by 2050, as the costs of green hydrogen drop, it could compete head-to-head with traditional methods. Facility-level optimization in several iron ore producing countries focuses on locations with access to renewable energy sources and high-quality iron ore, accelerating the economic and environmental viability of hydrogen-based steel production.

DRI made with natural gas can cut carbon emissions in half compared to a coal blast furnace. The technology is catching on worldwide. DRI facilities accounted for about 36% of iron-making capacity under development, per a 2024 Global Energy Monitor and 9% of operational capacity.

To truly produce low-carbon steel, however, a DRI facility would need to fuel its DRI process with green hydrogen — the version of the hydrogen fuel made with completely carbon-free electricity — instead of natural gas, said Hilary Lewis, the steel director at climate advocacy nonprofit Industrious Labs.

The 45V tax credits created by the Inflation Reduction Act enable the 2025 price difference between DRI using natural gas and green hydrogen would be manageable. Natural gas powered DRI yields steel at a levelized price of about $800 per ton, according to calculations by clean energy think tank RMI. Green hydrogen would raise the steel price to about $964 per ton. The typical passenger car uses about one ton of steel.

Research indicates that green steel produced via hydrogen-based metallurgical reduction processes contains only 1-2 weight parts per million hydrogen in its final liquid form, similar to steels processed through current advanced methods. This shows the potential for hydrogen to play a significant role in creating environmentally friendly steel without compromising quality.

So, is hydrogen the secret ingredient for a greener steel industry? The signs are promising. Hydrogen holds the key to a sustainable and environmentally friendly future for the steel industry. Together with ongoing research and efficiency advancements, the large-scale implementation of hydrogen in steelmaking could significantly reduce the industry's carbon footprint, marking a critical step towards a greener future.

The use of green hydrogen in oil refining is an emerging trend aimed at reducing carbon emissions. Green hydrogen is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity generated from renewable or nuclear sources. This method of production ensures that green hydrogen is free of greenhouse gas emissions, which is crucial for its role in decarbonizing industries like oil refining.

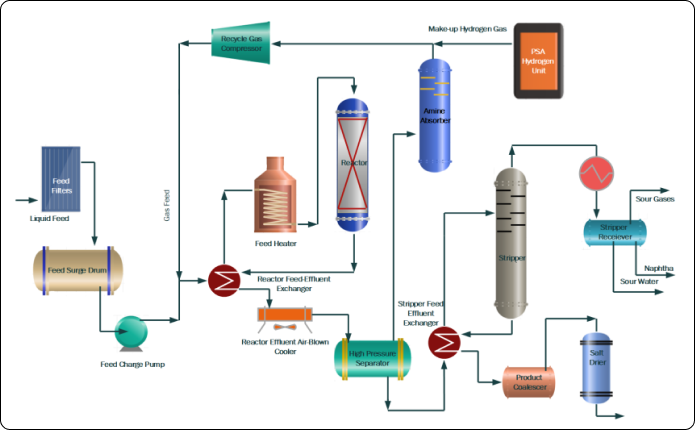

Hydrogen plays a pivotal role in oil refining, primarily in the processes of hydrotreating and hydrocracking. These two processes are critical in refining because they are responsible for consuming over 90% of the hydrogen used in the sector. Hydrotreating is essential for reducing sulfur content in finished petroleum products. Sulfur compounds, if not removed, can lead to harmful emissions when the fuel is burned and can also corrode engines and other machinery. By removing sulfur, hydrotreating ensures that the fuels meet environmental standards and are safer for use in vehicles and machinery.

Hydrocracking, on the other hand, is a process that breaks down heavier fractions of petroleum into lighter, more valuable products like gasoline and jet fuel. This process is particularly important for maximizing the yield of high-value products from crude oil. Hydrocracking involves breaking down larger hydrocarbon molecules into smaller ones, a reaction that requires hydrogen. The process increases the amount of usable fuel derived from crude oil, making it a key step in maximizing the efficiency and profitability of oil refining.

Currently, the majority of the hydrogen used in these processes is sourced as a by-product from other refinery operations, such as catalytic reforming and ethylene cracking. Catalytic reforming involves the conversion of heavy naphthas into high-octane gasoline components, while ethylene cracking is primarily concerned with the production of ethylene, a building block for various petrochemicals. Both of these processes generate hydrogen as a by-product, which is then used in hydrotreating and hydrocracking.

However, there is a growing trend towards replacing this hydrogen with low-carbon alternatives, particularly green hydrogen. This shift is driven by the increasing stringency of environmental regulations and the global commitment to reducing carbon emissions. Green hydrogen, produced through the electrolysis of water using renewable energy sources, offers a much lower carbon footprint compared to conventional hydrogen production methods. The integration of green hydrogen into oil refining can significantly reduce the carbon emissions associated with these processes.

Despite its environmental benefits, green hydrogen production is more expensive than traditional methods due to higher electricity costs and the limited availability of zero-carbon power. This means that for green hydrogen to be more widely adopted in oil refining, there needs to be a decrease in power costs and an increase in the efficiency and availability of zero-carbon power sources.

There are ongoing efforts and projects aimed at integrating green hydrogen into refinery processes. For instance, the REFHYNE project in Germany is working on installing and operating a large electrolyser at a refinery to provide bulk quantities of green hydrogen. This project is a part of a broader move towards decarbonizing the refining process and reducing emissions, a trend that is expected to continue and expand in the 2020s.

The potential market for low-carbon hydrogen in oil refining is significant. By 2050, the demand for low-carbon hydrogen in the global refining sector could reach 50 million tonnes per annum. This transition to green hydrogen could play a crucial role in reducing up to 35% of refining carbon emissions.

In an era where environmental concerns are paramount, the food and beverage industry is experiencing a paradigm shift. Historically reliant on fossil fuels, the industry is now embracing hydrogen as a pivotal element in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting sustainability.

Green hydrogen is increasingly being explored for its potential in various industrial processes, including the hydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids in animal and vegetable oils. This process is a key step in producing solid fats from liquid oils, which are then used in food products like margarine and other spreads.

Hydrogenation involves the conversion of unsaturated fatty acids to saturated fatty acids through a chemical reaction that adds hydrogen to these acids. This process alters the molecular structure of the fatty acids, converting carbon-carbon double bonds into single bonds. Unsaturated fats, which are generally liquid at room temperature due to their molecular structure, become saturated through hydrogenation and thus solidify. This is because the straighter chain of saturated fats allows them to pack more closely together, resulting in a solid form at room temperature.

Vegetable oils, for instance, are typically polyunsaturated and are transformed into semi-solid or solid fats through hydrogenation. This process is crucial in the food industry as it allows the conversion of inexpensive and abundant vegetable oils into more solid forms like margarine, cooking fats, and spreads. During the hydrogenation of vegetable oils, the number of double bonds that are hydrogenated is carefully controlled to produce fats with the desired consistency, such as soft and pliable margarine.

Furthermore, hydrogenation also affects the stability and melting characteristics of the resultant fats. The selectivity of the hydrogenation process, such as the preference for hydrogenating polyunsaturated fatty acids over monounsaturated ones, and the production of trans-isomers, are important factors that influence the final properties of the hydrogenated fat. This process is not only a method to alter the physical properties of the fats but also serves as a means to increase their shelf life and stability, as saturated fats are less prone to oxidation and rancidity compared to unsaturated fats.

In the context of green hydrogen, its usage in such industrial processes represents a move towards more environmentally sustainable practices. Green hydrogen, produced through the electrolysis of water using renewable energy sources, offers a cleaner alternative to traditional hydrogen production methods, which often rely on fossil fuels.

The transition to hydrogen has become a catalyst for innovative food processing technologies.

Pioneering this change, researchers at West Virginia University (WVU) are developing hydrogen-based technologies tailored for the food and beverage sector. A standout innovation is a flexible fuel furnace that efficiently utilizes hydrogen to generate the essential hot water and steam for product processing. Boasting an impressive 98% energy utilization efficiency and minimal nitrogen oxide emissions, this furnace exemplifies the environmental and operational benefits of hydrogen. It's adaptable too, capable of running on natural gas or hydrogen blends, thus easing the transition from fossil fuels.

WVU's collaboration with local industry partners, such as Mountaintop Beverage and Morgantown’s Neighborhood Kombuchery, is pivotal. These partnerships focus on refining production processes to curb energy consumption and emissions, while maintaining product safety and quality through rigorous microbial testing and sensory analysis.

The shift to green hydrogen technology is gaining momentum among major food corporations. Quorn, Unilever, and Nestle, for example, are actively exploring green hydrogen for their production facilities to meet ambitious climate goals. These moves towards green hydrogen, generated from renewable energy sources, are major steps towards a carbon-neutral operation, offering sustainable solutions for processing liquid oils, energy storage, and transportation challenges in the industry.

Hydrogen technology is more than an alternative energy source; it's a driver for a more sustainable and environmentally friendly future in the food and beverage industry. With ongoing research, development, and collaboration, hydrogen stands poised to revolutionize manufacturing processes, steering the sector towards a greener horizon.

As the world increasingly turns its focus towards sustainable and environmentally friendly practices, the glass and ceramics industries are undergoing a significant transformation. Central to this change is the integration of hydrogen, especially green hydrogen, as a key energy source. This shift not only represents an adaptation to global decarbonization efforts but also a proactive move towards innovative industrial practices.

In the production of float glass, the integration of hydrogen, particularly green hydrogen, has been explored as an alternative to fossil fuels to provide heat and prevent oxidation.

Float glass furnaces have been traditionally powered by natural gas. Companies like SCHOTT are at the forefront of using hydrogen as an alternative to traditional fossil fuels in glass production. Their experiments with 100% hydrogen demonstrate a shift towards more climate-friendly manufacturing processes. At 100% hydrogen usage, the flames become less luminous and almost invisible, which is a notable characteristic due to the lower soot concentration in hydrogen flames compared to natural gas or oil flames.

Saint-Gobain has successfully experimented with using over 30% hydrogen in manufacturing flat glass, significantly reducing CO2 emissions.

There are ongoing research efforts to decarbonize the glass industry to align with the Paris Climate Agreement goals. One approach being considered is the use of hybrid furnaces that can utilize green hydrogen as a fuel source, alongside electric melting furnaces. However, questions remain about the supply, availability, and economic viability of green hydrogen for this purpose. The transition to these technologies is a part of a long-term roadmap with milestones set for the upcoming decades, including the complete replacement of natural gas-fired melting furnaces by 2045.

The ceramics industry is actively exploring the use of green hydrogen as a sustainable and efficient energy source, driven by the global shift towards decarbonization and the need to meet environmental targets.

Here are some key developments and projects in this field:

The Iris Ceramica Group has embarked on a groundbreaking project to create the world’s first ceramics factory powered by green hydrogen. This initiative, a collaboration with Snam, involves the development of a production site in Castellarano, Italy, designed to use green hydrogen generated from solar energy. This innovative approach is expected to significantly reduce CO2 emissions and marks a major step towards sustainable ceramic manufacturing. The project aims for a blend of green hydrogen and natural gas, eventually transitioning to 100% hydrogen use for zero-emissions production.

Another significant project is the GreenH2ker initiative, a collaboration between Iberdrola and Porcelanosa. This project focuses on using green hydrogen and heat pump technology to power the heat-intensive processes in ceramic production. The goal is to replace a significant portion of the natural gas used in these processes with green hydrogen, thereby reducing CO2 emissions. The project also includes the installation of an on-site electrolyzer powered by a solar photovoltaic plant, emphasizing the synergy between renewable energy sources and hydrogen production.

These initiatives are part of a broader movement in the ceramics industry to adopt more sustainable practices. The integration of green hydrogen in ceramic production aligns with the European Union's decarbonization targets and represents a significant shift towards cleaner, more sustainable industrial processes. As these projects progress, they are expected to offer valuable insights and pave the way for wider adoption of green hydrogen in high-temperature industrial processes, not only in ceramics but also in other sectors like glass and metal industries

The glass and ceramics industries are on a transformative journey with hydrogen at the forefront. By embracing this clean energy source, these industries are not only reducing their carbon footprint but are also paving the way for innovative practices and sustainable growth. The ongoing projects and research in these fields are vital in achieving global climate goals and creating a more sustainable industrial landscape.

In the realm of pharmaceutical manufacturing, a quiet revolution is underway, one that promises to reshape how essential medicines and vitamins are produced. At the heart of this transformation is hydrogen, a simple yet powerful element that is redefining the industry's approach to sustainability and efficiency.

Let’s delve into the increasingly pivotal role of hydrogen in pharmaceutical processes, exploring innovative methodologies and their profound implications. From the precision of hydrogenation in vitamin synthesis to the groundbreaking integration of hydrogen with electricity for drug production, we uncover how this element is not just a part of the industry but is becoming instrumental in driving its future.

Hydrogen plays a pivotal role in the production of vitamins and pharmaceuticals, particularly through hydrogenation. This chemical reaction, often utilizing catalysts like platinum or nickel, is instrumental in the synthesis of various essential compounds.

Hydrogenation is vital in chiral chemistry, crucial for complex pharmaceuticals, and is notably significant in producing (+)-biotin, involving the stereoselective hydrogenation of a trisubstituted olefinic bond.

Incorporating hydrogenation in pharmaceutical manufacturing presents economic advantages. The process's efficiency and environmental friendliness translate to cost savings and compliance with increasingly stringent environmental regulations.

A groundbreaking approach, emerging from the collaborative efforts of researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and industry leaders at Merck & Co., is set to redefine pharmaceutical manufacturing. This innovative technique ingeniously combines hydrogen with electricity, a concept inspired by the principles of hydrogen fuel cell technology, which is primarily known for its application in clean energy generation.

This new method is a departure from traditional pharmaceutical manufacturing techniques, which often rely heavily on metals like zinc. By integrating hydrogen and electricity, the process dramatically reduces the reliance on such metals, thereby addressing key environmental concerns associated with metal mining and disposal. This reduction in metal usage also translates to significant economic benefits, as it curtails both the material costs and environmental remediation expenses associated with metal waste.

At the core of this method is the utilization of quinone, an organic compound, to extract electrons from hydrogen. This aspect of the process is particularly innovative, as it enhances the efficiency and sustainability of drug production. Quinones, being versatile in their redox properties, enable a more controlled and precise electron transfer process, which is essential in the complex chemical reactions involved in drug manufacturing. The ability to conduct reactions without water is another notable advantage of this method. In many pharmaceutical processes, the presence of water can interfere with the desired chemical reactions, so a water-free approach opens up new avenues for the synthesis of more complex and sensitive drugs.

The successful industrial application of this technique could be a game-changer, marking a significant stride towards a more sustainable and efficient pharmaceutical industry. It also signals a potential shift in the broader chemical manufacturing sector, where the principles of green chemistry can be further embraced.

In conclusion, the evolving role of hydrogen in pharmaceutical manufacturing marks a significant leap towards a greener and more efficient future. The innovative techniques of hydrogenation and the integration of hydrogen with electricity not only underscore the industry's commitment to sustainable practices but also pave the way for cost-effective and environmentally friendly drug production. This revolution, rooted in cutting-edge research and collaboration, positions hydrogen as a key driver in reshaping pharmaceutical manufacturing, holding great promise for both the industry and global health.

More than 95% of hydrogen used in the chemical industry is currently produced through methods like steam methane reforming, a process with significant environmental impacts. The shift towards green hydrogen production is essential for sustainability.

Green hydrogen is increasingly being adopted in various industries, including the production of fertilizers, explosives, and other chemicals. It's not only a critical element in creating various chemicals but also a key enabler for the industry's shift towards sustainability.

Countries like Australia, Canada, Chile, China, and India are investing in green hydrogen projects. For example, Australia is developing a large renewable energy export facility and a hydrogen valley in New South Wales. Canada's Project Nujio'qonik aims to be the country's first commercial green hydrogen/ammonia producer. In Chile, significant investments are being made to finance green hydrogen projects as part of their clean energy goals. Meanwhile, China, a global leader in hydrogen production, is increasing its green hydrogen output, and Germany has invested heavily in electrolyzer capacity to boost green hydrogen production.

Green hydrogen is set to transform the fertilizer industry significantly. It can be used to produce green ammonia, which is essential for nitrogen fertilizers. Countries with access to cheap renewable energy sources, like Saudi Arabia and Australia, could become significant producers of green hydrogen and green ammonia. This shift is driven by the need to decouple fertilizer production from fossil fuels and reduce carbon emissions. However, the transition to green ammonia will require technology upgrades and significant investment. The cost of green ammonia is currently higher than that produced from fossil fuels, but this is expected to change by 2030 with technological advancements and increased access to renewable power sources.

Green hydrogen also needs to be used in the production of explosives and various chemicals. The production process for many chemicals requires hydrogen, and traditionally, this has been sourced from fossil fuels. Transitioning to green hydrogen in these processes can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of these industries. However, the use of green hydrogen in these sectors is still developing, with more research and investment needed to fully realize its potential.

The transition to green hydrogen faces several challenges, including the need for technology upgrades, policy support to make the transition economically viable, and reducing higher production costs compared to grey hydrogen (hydrogen produced from fossil fuels and releasing about 5 tons of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere for each ton of hydrogen produced). However, the potential benefits, such as reduced carbon emissions and less dependence on fossil fuels, make green hydrogen a promising option for the future of these industries.

Hydrogen's multifunctionality in the chemical industry is undeniable. As the industry moves towards a more sustainable and circular economy, hydrogen, especially in its green form, stands out as both a challenge and an opportunity. This transition will not only aid in achieving net-zero targets but also open up new product’s sustainable revenue streams for chemical companies.