ITHACA, N.Y. — A faded-red wellhead emerged in the middle of a pockmarked parking lot, its metal bolts and pipes illuminated only by the headlights of Wayne Bezner Kerr’s electric car. He stepped out of the vehicle into the dark, frigid evening to open the fence enclosing the equipment, which is just down the road from Cornell University’s snow-speckled campus in upstate New York.

We were there, shivering outside in mid-November, to talk about heat.

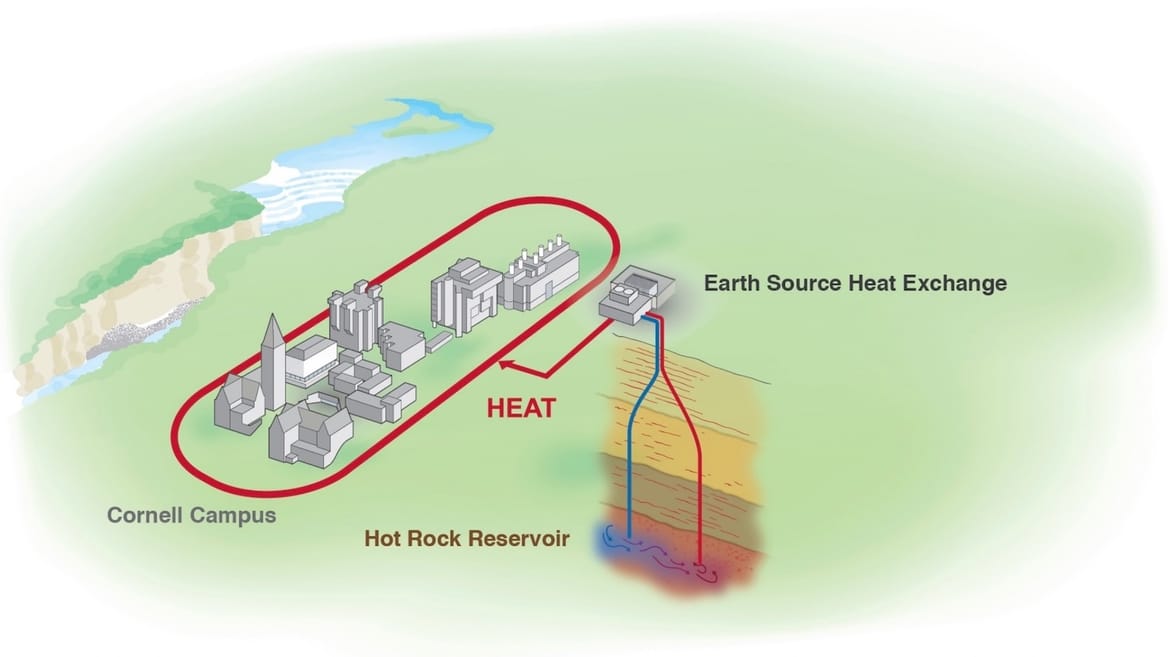

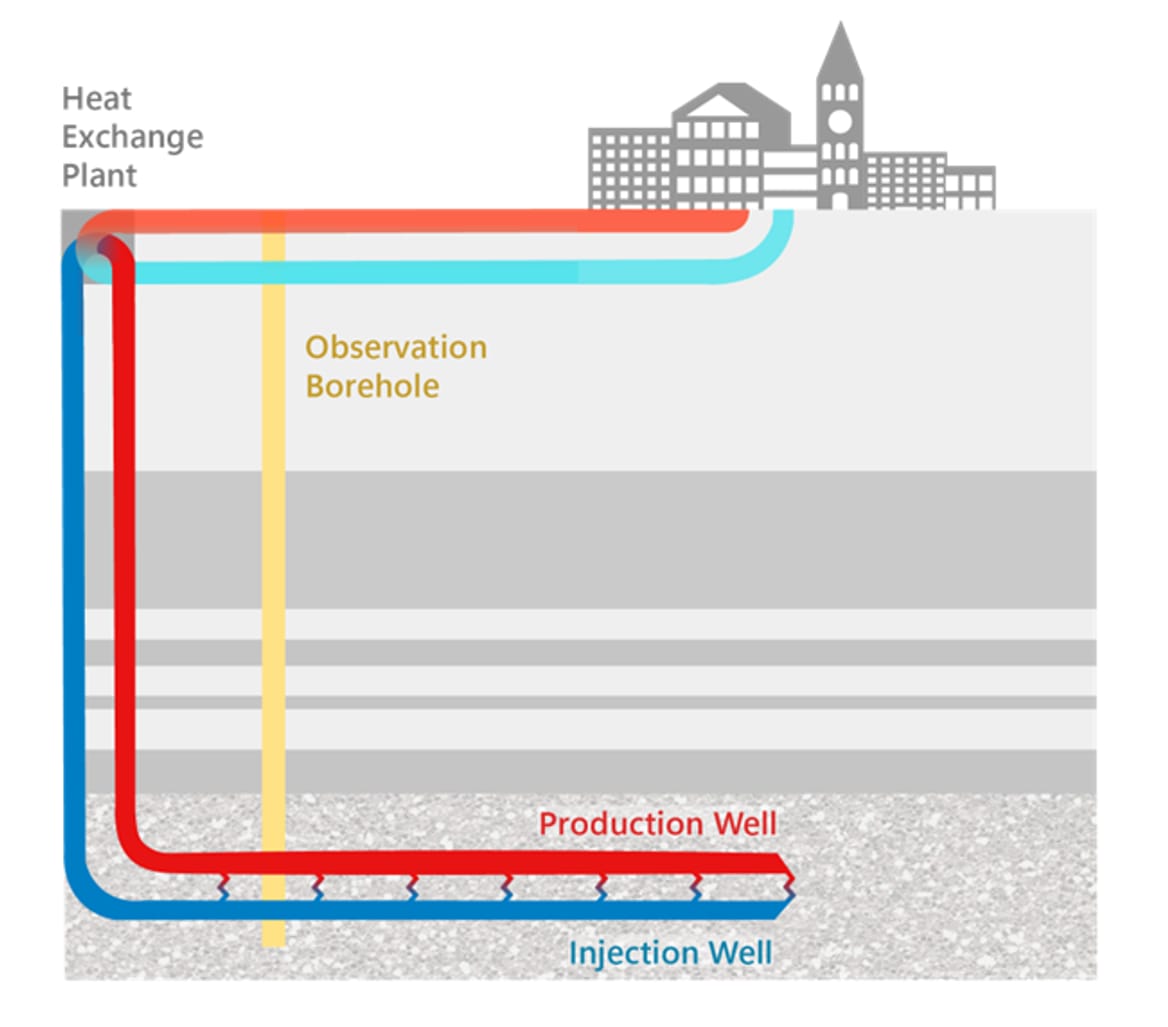

Bezner Kerr is the program manager of Cornell’s Earth Source Heat, an ambitious project to directly warm the sprawling campus with geothermal energy pulled from deep underground. The wellhead was the tip of the iceberg — the visible part of a nearly 10,000-foot-long borehole that slices vertically through layers of rock to reach sufficiently toasty temperatures. Cornell is using data from the site to develop a system that will replace the school’s fossil-gas-based heating network, potentially by 2035.

“We can’t decarbonize without solving the heat problem,” Bezner Kerr repeated like a refrain during my visit to Ithaca.

The Ivy League university is trying to accomplish something that’s never been done in an area with rocky geology like upstate New York’s. Most existing geothermal projects are built near the boundaries of major tectonic plates, where the Earth’s warmth wells up toward the surface. Iceland, for example, is filled with naturally heated reservoirs that circulate by pipe to keep virtually every home in the country cozy. And in Kenya and New Zealand, geothermal aquifers supply the heat used in industrial processes, including for pasteurizing milk and making toilet paper.

Bezner Kerr and I, however, stood atop a multilayered cake of mudstone, limestone, sandstone, and other rocks — seemingly everything but water. To access the heat radiating beneath our feet, his team will need to create artificial reservoirs more than 2 miles into the earth.

America’s geothermal industry has made significant strides in recent years to generate clean energy in less obvious locations, and it’s done so by adapting tools and techniques from oil and gas drilling. One leading startup, Fervo Energy, is developing “enhanced geothermal systems” in Utah and Nevada to produce clean electricity around the clock. The approach involves fracking impermeable rocks, then pumping them full of water so that the rocks heat the liquid, which eventually produces steam to drive electric turbines.

Earth Source Heat plans to use similar methods to drill a handful of super-deep wells and create fractures near or within the crystalline basement rock, where temperatures are consistently around 180 degrees Fahrenheit, no matter the weather above. The project is also unique in that, among next-generation systems, it’s focused only on heating buildings — not supplying electricity — for the nearly 30,000 students and faculty. That’s because heat represents the biggest source of Cornell’s energy use, and its largest obstacle to reducing planet-warming emissions.

On the chilliest days, the campus can use up to 104 megawatts of thermal energy, which is more than triple its peak use of electrical energy during the year.

Such a ratio poses a big conundrum for not only large institutions like Cornell but also any cold-climate cities that burn fossil fuels to keep warm, as well as manufacturing plants that require lots of steam and hot water for steps as varied as fermenting beer, making oat milk, and sterilizing equipment.

Right now, one of the most immediate ways to cut emissions from thermal energy use is to replace gas-fired boilers and the like with heat pumps and other electrified technologies. But that can substantially increase a city’s or factory’s electricity use. In an ideal world, all the new power demand would be satisfied by renewable energy projects and served by a modern and efficient grid, helping limit the costs and logistical headaches of ditching fossil fuels.

In reality, though, the U.S. electricity system is straining to keep up with the emergence of data centers, new factories, and electrified buildings and vehicles. Utilities are pushing plans to build new gas-fired power plants and proposing higher electricity rates to cover the costs. New York, for its part, is failing to meet its own goals for installing gigawatts of new renewables and energy storage projects by 2030, in part because of barriers to permitting projects in the state. New York’s independent grid operator recently warned of “profound reliability challenges” in coming years as rapidly growing demand threatens to outpace supply.

Geothermal heating could provide a way to curb thermal-energy emissions without burdening the electric system even more, said Drew Nelson, vice president of programs, policy, and strategy with Project InnerSpace, a nonprofit that advocates for geothermal energy use.

“Electrification is great, but that’s a whole lot of new electrons that need to be brought onto the grid, and a whole lot of new transmission and distribution upgrades that need to be made,” Nelson said by phone. “For applications like industrial heat, or building heating and cooling, geothermal almost becomes a ‘Swiss Army knife,’ in that it can help reduce demand.” Using geothermal energy directly is also far more efficient than converting it to electricity, since a lot of energy gets lost in the process of generating electrons.

Still, deep, direct-use geothermal systems like the one Cornell is developing are relatively novel, and many manufacturers and city planners are either unfamiliar with the solution or unwilling to be early adopters.

Sarah Carson, the director of Cornell’s Campus Sustainability Office, explained that Earth Source Heat is intended to reduce technology risks and costs for other major heat users that might benefit from geothermal, including the region’s dairy producers and breweries. We spoke inside her office, which is attached to the 30-megawatt gas-fired cogeneration plant that currently provides both electricity and heating for the campus.

“We’re working really hard to build a ‘living lab’ approach into the ethos of how we approach things,” she said. “Can we not only take care of our own [carbon] footprint but also help develop and demonstrate solutions that could scale out?”

Earlier on that overcast day, Bezner Kerr and I drove to the shores of Cayuga Lake.

Winds whipped up the grayish-blue waters, which form one of the 11 long, skinny Finger Lakes that glaciers etched into the Earth millions of years ago. Cayuga Lake is, in a way, the inverse of a heated geothermal reservoir. Cornell uses the chilly lake to cool the water that circulates across campus, replacing the need for industrial chillers that use lots of refrigerants and electricity.

Inside the Lake Source Cooling facility, giant blue pipes intersect through pieces of equipment called heat exchangers. Since heat naturally flows from hotter objects to colder ones, the lake water acts like a magnet, pulling heat out of the campus-water loop. The lake-water loop then moves the heat down to the cold bottom of Cayuga, and the cycle repeats. Bezner Kerr said Earth Source Heat will do the same but in reverse, flowing hot water up to the surface and returning the cooled-off water underground, where the earth can continuously reheat it.

Initially, he said, the new geothermal system will connect to an existing underground hot-water loop that heats East Campus, including two energy-intensive research buildings. This first stage is expected to cost over $100 million and could be completed in the next few years. Depending on how Earth Source Heat performs, the university might expand the system to warm around 150 large buildings on the main campus.

The university’s approach is far more intensive than the geothermal systems that cities and high-rise buildings are increasingly deploying across the country. An underground thermal network in Framingham, Massachusetts, consists of 90 holes drilled about 650 feet deep that heat 36 homes and commercial buildings; it also uses electric heat pumps to boost the temperatures coming out of the ground. Cornell’s home city of Ithaca has proposed piloting its own thermal network to heat and cool buildings on a city block.

Jefferson Tester, a Cornell professor and the principal scientist for Earth Source Heat, said these shallower geothermal systems aren’t as practical for heating the 15-million-square-foot campus.

For one, the university would need to drill north of 10,000 smaller wells to adequately warm all its buildings, instead of the five very deep wells it has planned. And digging deeper into the ground will allow Cornell to use the heat straight away, without adding heat pumps.

Tester joined Cornell in 2009 to help launch Earth Source Heat, which is part of the university’s larger plan to achieve a carbon-neutral campus in Ithaca by 2035. For over a decade, faculty and engineers gathered data and developed models to get a better sense of the region’s geology, heat resources, and potential for drilling-related earthquakes, often in partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy.

But to fully grasp the subsurface’s conditions, they needed to drill. “And once you understand the geology well enough … you could go anywhere in this region” to harness geothermal energy, Tester said.

In 2022, the university drilled that first 10,000-foot-long hole, which is called the Cornell University Borehole Observatory, in the parking lot. “It was the same level of intensity as an oil-and-gas exploration rig,” Bezner Kerr recalled. “It was oil-and-gas workers drilling a well that produces knowledge instead of producing hydrocarbons.” Cornell received about $7 million from the Energy Department for the project, which cost around $14 million to deploy.

Now the team is ready to drill again, though the timing of the next phase is up in the air amid funding uncertainty.

Earth Source Heat wants to reopen the borehole, deepen it, and use fiber-optic cables and other tools to study how the rock responds to stress and high-pressure injections of water — data that will inform the design of the final system. In 2024, during the Biden administration, Cornell applied for over $10 million from the Energy Department for the project, with plans to line up drilling equipment this year. But the Trump administration hasn’t yet responded to the request.

If the team can finish the second phase of its borehole observatory, the next step will be to drill a demonstration well pair — two vertical spines with horizontal legs, and fractured rocks in between — to begin heating part of East Campus.

The drilling delays come as Cornell faces growing criticism from climate activists both on and off campus, who argue that the university isn’t reducing its emissions nearly fast enough to help limit global temperature rise. Cornell on Fire, a climate-justice group, has raised concerns that Cornell is using Earth Source Heat as a “delay tactic to avoid undertaking necessary actions now on other critical fronts.” The group says Cornell should immediately provide more adequate funding for the geothermal project and be more transparent about its timeline for implementing the system.

Meanwhile, Carson said her office is feeling pressure from climate advocates to start replacing the current gas-fueled heating network with electrified technologies like heat pumps and electric boilers. But she and her colleagues believe that swiftly boosting Cornell’s electricity demand would require increasing gas-fired power generation off campus, reducing the school’s CO2 footprint on paper without lowering emissions overall. Even so, Carson’s team is evaluating a range of potential solutions, including heat-storing batteries and shallower geothermal networks, in case Earth Source Heat doesn’t work as well as hoped.

These tensions highlight the tricky reality of developing big and novel clean-energy projects. A well-designed, smartly managed geothermal system could help decarbonize heat for buildings and factories over the course of many decades. But finding the right locations and best ways to install those networks takes careful planning, patience, and significant upfront investment. That can be tough to stomach, both for project investors antsy to see financial returns and for citizens eager to dump polluting fossil fuels today.

“We’ve got to be thinking about a long-term, multigenerational commitment” for tackling climate change, Tester said. “And that is really hard for people.”

To Bezner Kerr, it doesn’t seem like larger discussions on decarbonization fully acknowledge just how big of a challenge heat represents — and what it would mean to electrify all the country’s heating needs. We were speaking then in his office, where a grayish chunk of Potsdam sandstone retrieved from deep below sat in a white plastic bucket next to his desk.

“It’s like there’s this huge train coming down the tracks,” he said. “And nobody realizes we’re about to get flattened by this thing if we do it wrong.”

A correction was made on Dec. 10, 2025: This story originally misstated Cornell on Fire’s position on the Earth Source Heat project; this piece has been updated to more accurately reflect the group’s stance.